St Peter and St Paul: 29 June 2025

Readings: Acts 12.1–11; Psalm 125; 2 Timothy 4.6–8, 17, 18; Matthew 16.13–19

May the words of my mouth

and the meditation of my heart

be acceptable in your sight, O Lord.

I wonder if you’ve ever been to Rome.

It’s somewhere I’ve been several times,

and one of the things I have done each trip

is visit the Vatican

and climb up the dome of the great basilica there.

It’s a bit of a slog,

some 500 steps to the top,

but when you get up there

you are rewarded

with some wonderful panoramic views across the city.

And you can also access the gallery

that runs around inside the dome.

From there

you get some really impressive views of the interior.

One thing you can see close up, for example,

is a Latin inscription

that runs full-circle around the dome.

In giant lettering it begins: “Tu es Petrus …”.

I’ll come back to these words in a moment.

– if you’re not too bothered about the height –

perhaps you can look straight down.

It’s a rather dizzying couple of hundred feet

but there beneath you

is the high altar,

with its great baldachino or canopy by Bernini.

And right in front of that altar

there’s a semi-circle of steps

leading further down,

down beneath the floor of the church.

Now these steps aren’t accessible to the public.

But if you could go down them,

and under the high altar,

you’d find yourself

standing among the remains

of an ancient Roman cemetery.

Because those steps take you down

to the site of the tomb of St Peter.

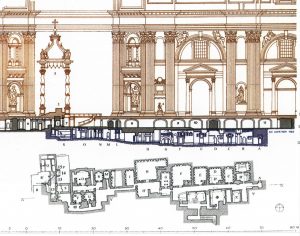

Of course, the church we see today

was completely rebuilt

some 4 or 500 years ago,

in the flamboyant baroque style.

But they rebuilt it

on exactly the same site

as the previous church,

with the high altar

in exactly the same place as before.

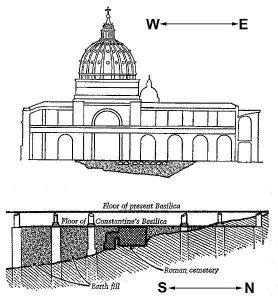

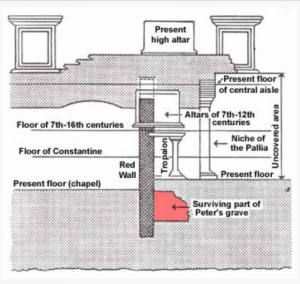

Section showing the various altars and floor levels and their relation to the tomb of St Peter. [Liturgical Arts Journal]

over a thousand years earlier,

in the 300s,

as soon as Christianity had been legalized.

It was built

– with considerable difficulty –

right on top of this ancient Roman cemetery;

and awkwardly,

on the side of a hill;

all carefully positioned

so that the high altar

was directly over

one particular tomb*.

And next to this cemetery

there had been an arena,

the Circus of Nero,

and that’s where many early Christians

had been put to death,

accused by Nero

of causing the great fire of Rome.

Peter himself was among those executed,

said to have been crucified

– crucified upside-down according to tradition.

Paul was a Roman citizen though,

so he was spared crucifixion

– he was beheaded

(and buried)

elsewhere in the city.

Other Christians were rounded up

and put to death in the arena:

torn apart by wild beasts,

or forced to fight to the death as gladiators,

burned alive,

or killed in some other barbaric Roman spectacle.

And it is

this first great persecution

– the martyrdom of Peter and Paul and many others –

that we are remembering today.

It is those martyrs, Peter, Paul and the others,

that we commemorate

and hold in great honour.

It was probably around the year 64,

so just 30 years or thereabouts

after Jesus had walked around Galilee

and come to Caesarea Philippi.

And we heard a bit about that

in today’s gospel reading.

Peter,

Simon Peter,

at Caesarea Philippi

acclaiming Jesus as the Messiah.

You can sort of imagine him blurting it out, can’t you?

The first person to put into words

what he, and perhaps others,

had been thinking.

And Jesus recognizes the leap that Simon Peter has made.

This is when Jesus gives him the nickname:

“Rock”, which of course is what “Peter” means.

“You are the rock,”

he says to him

– “you are Peter”.

Remember that inscription around the dome at the Vatican?

This is the verse that it quotes, in Latin:

“Tu es Petrus”, “you are Peter”.

And in the 30 years or so

since that moment at Caesarea Philippi,

first Peter, the rock, and then Paul

had built the early church

from tiny beginnings

to something that was starting to be noticed

– even in the heart of the Roman Empire.

Because these Christians were a bit different

from your everyday Roman.

They didn’t join in things

that good Romans were supposed to do,

like … sacrificing at the temples,

or considering the emperor to be a god.

And although a few of them were wealthy,

many were slaves or ex-slaves

or very definitely among the poor and oppressed.

Because it was often among

the poor and the oppressed

that Peter and Paul

and others

preached the good news of the kingdom of God.

“Blessed are the poor, the hungry,

the sick, the persecuted”

Jesus had said

– that’s definitely good news when you are poor and oppressed.

Perhaps this message of hope

(and – dare I say it? –

social revolution?)

was already causing a stir in Roman society.

There must have been something they were doing

that attracted the attention of the ruling class

– of the Emperor Nero,

when he was looking for someone to blame

for that disastrous fire.

And I wonder to what extent

this message of hope

– and social revolution –

can still cause a stir in our modern society.

Or have we made it so bland,

or so other-worldly,

that it simply doesn’t impinge

on the thoughts of our fellow citizens?

Most of them have not just given up believing,

they have even given up disbelieving

– they just don’t care.

But as Christians

it is our job to care.

Peter and Paul,

as we have heard,

were martyrs,

a Greek word meaning witnesses.

In their life

and

by their death

they and others were witnesses:

witnesses to the reconciling love of God,

witnesses to the good news

of the rule of God that Jesus had proclaimed.

And just like Peter, just like Paul,

we too are witnesses.

We are God’s witnesses

here in St Ives in 2025.

We are the ones

tasked with representing God –

representing God

to the world in which we live.

We are the ones

who are called to bear witness

to what God has done in our lives.

To bear witness

to what Jesus means in our lives.

Now I trust and hope that none of us

will be called to bear witness

in the face of persecution and violent death.

So we will not be martyrs

in the way that the word is used nowadays.

We will not be martyrs like Peter and Paul.

But we can be God’s witnesses

among our friends and family,

our acquaintances and colleagues,

and those we meet.

Does that sound a daunting task?

Well, maybe it does, yes!

So, let’s start with something

any of us can do.

Let’s think for a moment.

Do you have a ready answer

when someone asks

what do you do on a Sunday morning?

Do you have a ready answer

when someone asks why do you go to church?

Do you have a ready answer

if someone asks you about Jesus?

If I’m honest, I’m not sure I do.

So my challenge to each one of us is this:

find time this week to spend a few minutes

considering how you would answer those questions

– in just a short sentence or two.

How you might answer those questions

in a way that encourages engagement and further interest.

And little by little,

person by person,

we will,

like Peter and Paul

and all the saints before us,

help to build God’s kingdom

here on earth

as it is in heaven.

Amen.

* This is a slight over-simplification. In the first Church, as originally built under Constantine, the tomb was visible. It was Gregory the Great (in about 594) who raised the floor of the sanctuary by several feet and placed the altar over the tomb. That altar was at a level several feet below the floor of the rebuilt basilica that we see today.

0 Comments

Nicaea and the date of Easter

This article was first published in the June 2025 issue of Transforming Worship News (formerly Praxis News of Worship).

The date of Easter is often regarded as rather complicated, too complicated for nearly everyone to worry about. But it links us with the origin of the annual festival, and the way the early Church celebrated the resurrection.

When the Emperor Constantine decided that Christianity was the best hope of unifying his empire, he found disagreement on several topics, including the nature of Christ and the date on which to hold an annual celebration of his resurrection. The Council of Nicaea in 325 attempted to resolve both issues, agreeing a statement of belief and formalizing the date of Easter.

The story begins with the Jewish festival of Passover, held at the first full moon of the spring, when the moon lights the sky all night. In the Jewish lunar calendar this day is 15 Nisan, and the previous day, 14 Nisan, is the day of preparation. In the late afternoon of that day, until the Temple was destroyed, Passover lambs were slaughtered in the Temple precincts. They were then roasted and eaten at the Passover meal that began with the full moon at sunset, the start of 15 Nisan. In the fourth gospel, the crucifixion was on 14 Nisan, and in the synoptics on 15 Nisan.

There is no explicit evidence in the New Testament of a yearly Easter. The focus in the early Church was the weekly celebration of the resurrection on the first day of the week, every Sunday. Although it is not entirely clear – and there may have been a cover up – it seems that Christians in Jerusalem and the Jewish diaspora did keep an annual festival, but Gentile Christians probably didn’t. The former group kept an annual celebration of both the crucifixion and resurrection on 14 Nisan, whichever day of the week that fell on.

Perhaps influenced by this annual feast kept in the diaspora, other Christians began to observe it and a fast on the previous day. But rather than keeping it on 14 Nisan they celebrated the following Sunday, the day of the weekly commemoration of the resurrection. Perhaps just as today, it was more convenient to transfer weekday festivals to Sunday.

These two groups co-existed until at the end of the second century, Pope Victor I controversially excommunicated those who kept 14 Nisan – the Quartodecimans (or “fourteeners”). A century later the dispute had not ended although the Quartodecimans were a distinct minority. So when, commanded by Constantine to agree a common date, the bishops assembled at Nicaea it was not surprising that majority opinion, favoured by Rome and other major sees, prevailed. The Council ruled that the annual paschal feast, celebrating the resurrection, should be observed on the Sunday after the first full moon of the spring, the full moon after the equinox.

The Council did not prescribe how this might be determined in advance, and initially it was perhaps left to direct observation. Competing tables of dates soon emerged, frequently based on a 19-year lunar cycle that had been known since at least the Babylonians. The date of the equinox, which in the first century had fallen on 25 March, had by the fourth century drifted to 21 March. Tables from Alexandria were generally regarded as the best, and the declaration each year from that see of the date of Easter was usually followed, though for many years the see of Rome used different tables so occasionally Easter would fall on another date. Eventually the tables compiled and extended by the sixth-century monk Dionysius Exiguus were accepted as definitive. These continued in use throughout the Church, across the schism between East and West. As the middle ages wore on it was recognised that both lunar and solar components of the tables were increasingly inaccurate, but it was not until after the Reformation that Pope Gregory XIII unilaterally introduced a modified calendar with self-correcting lunar tables. Although these were gradually accepted by the churches of the Reformation they have not been adopted in the East, at least not for determining Easter.

In the twentieth century there were some moves to fix the date of Easter, but at the end of the century the World Council of Churches proposed abolishing calculated tables based on the approximate 19-year cycle and instead using accurate astronomical calculations of the equinox and the full moon as observed in the time zone of Jerusalem. They suggested this might be adopted in 2000 when both Eastern and Western calculations coincided on the same date. There was some support for this from Rome, from Anglicans and various churches of the Reformation and some Orthodox churches, but it was far from universal. In this 1700th anniversary year of Nicaea, when Easter dates again coincide, the WCC has re-iterated its proposal. Once again, it seems unlikely to gain enough support to be brought in.

Simon Kershaw remembers trying to calculate Easter from the tables in the BCP while enduring long sermons as a young chorister at Evensong. He has continued to calculate and write about the date of Easter.

2 Comments