The Baptism of Christ: 11 January 2026

Readings: Isaiah 42.1–9; Psalm 29; Acts 10.34–43; Matthew 3.13–end.

Words from today’s gospel reading:

“Jesus came from Galilee

to John at the Jordan,

to be baptized by him.”

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

When I was a bit younger,

we used to hear from time to time

about Billy Graham.

I’m sure many of you remember him too.

And for anyone who doesn’t,

he was a renowned American evangelist

from the 1950s through to the 90s.

And every few years

he would come to the UK

and hold rallies

in big arenas and stadiums,

and in the later years

technology meant

these could be simultaneously relayed

to smaller, local venues.

Perhaps you know someone

who attended one of these rallies –

maybe you even went to one yourself.

And Billy Graham

stood in a long line of “revivalist” meetings,

encouraging the young –

and the not so young –

to commit their lives to God.

There was a big revival

at the start of the 20th century,

largely in the USA,

which became the Pentecostal movement.

And a century earlier

revivalism had swept through

the villages and communities of Wales,

leading to a multiplicity of nonconformist chapels

throughout the country.

And we can look further back

to Methodism in the early 18th century

and back before that to earlier revivals.

And I wonder whether we can see

the ministry of John the Baptist in this same light.

There he stands

on the banks and in the shallows

of the River Jordan,

(the arena of his day perhaps?)

and the crowds come out

to hear him preach.

“All Jerusalem”, we are told.

And then instead of an “altar call”,

those who had heard his message

and wanted to be part of it

were dunked in the river water

as a sign that their sin was washed away

and they were beginning afresh.

John’s message

was that people needed to repent

and live a godly life

because judgement was coming,

indeed it would arrive,

he seems to have thought,

very soon.

And into this revivalist meeting comes … Jesus.

Now I want to make three points this morning,

and the first of these points is about – Jesus.

Because the presence of Jesus

here

with John the Baptist

gives the gospel writers

some pause for thought.

You see,

baptism was a sign

of repentance for sins committed,

and yet …

and yet

we believe Jesus was without sin.

So why was Jesus baptized?

In this morning’s reading

we can see

a bit of the struggle with this question.

In Matthew’s account

we heard Jesus and John

debating the issue –

and we can easily imagine

that these are the sort of arguments

that must have been debated

in the early years of the Christian Church.

But we also have to take into account

what is reported after the baptism.

Matthew tells us that

“just as [Jesus] came up from the water,

suddenly the heavens were opened to him

and he saw the Spirit of God

descending like a dove and alighting on him.“And a voice from heaven said,

‘This is my Son, the Beloved,

with whom I am well pleased.’ ”

If we read carefully,

we see that Matthew tells us

that it was Jesus himself

who saw the heavens open.

If we were to put this

in the language we would use about anyone else,

we might perhaps say

that this was a profound religious experience.

It had (as the theologian Joe Cassidy wrote)

“all the hallmarks of a powerful conversion experience,

a real turning-point”.

It was the moment when,

perhaps with hindsight,

Jesus recognised God’s special call to him,

the special relationship of a son to his father.

If indeed things happened something like this,

then Jesus must have subsequently

told others of his experience –

how he had been affirmed

in the ministry he was about to undertake –

that ministry

as a wandering preacher and teacher and healer

that would ultimately lead to Jerusalem

and to the Cross.

And for my part

I find the humanity of Jesus

profoundly meaningful.

But each of you

will have to come to your own conclusions

about how plausible this is.

And the second thing I want to say is about – us.

We too – nearly all of us here I imagine –

have been baptized.

For many of us

that happened when we were tiny infants.

It’s an event we are unable to remember.

For others,

being baptized was a deliberate decision

we made when we were older.

(And maybe – one or two of you

have not yet been baptized,

or perhaps you are considering being baptized.)

Well, today is an opportunity for us

to think about baptism,

to think about our own baptism

(or perhaps to think about

the possibility of our own baptism).

So one of the things

today’s gospel reading tells us

is that baptism is something

we share with Jesus.

In baptism we are incorporated into Jesus;

incorporated with Jesus

into the life of the Christian Church –

all those people who down the ages

have tried to follow the teaching of Jesus.

All those people who in our own time,

and in our own lives,

have tried to follow the teaching of Jesus.

Now in a few moments

we will take some time

to remember our own baptisms.

The water of baptism is life-giving

and brings refreshment.

But we shall also remember

that we don’t always live up to the promises we made

(or that were made on our behalf)

at our baptisms.

And yet the water of baptism

washes away our wrong-doings.

Through the water of baptism we are,

as I said, united with Jesus.

Through the water of baptism

we are given life –

new life in God’s kingdom,

new life where we are called

to share God’s love with the world:

sharing our food with the hungry,

and our houses with the homeless,

sharing our hope with those who are in despair,

sharing forgiveness and reconciliation

with those who have wronged us.

This is the life that our baptism inaugurates us

– each one of us – into.

And that brings me to my third point, my final point.

The story we have heard today

about Jesus’s baptism

marks the start of the story

of the adult Jesus.

Yes, we have heard over the last few weeks

the story of Jesus’s birth and the coming of the Magi,

and those passages form

a sort of prologue or prequel

to the rest of Matthew’s gospel.

But today’s reading is where the action starts.

It begins with the crowds

coming to see John the Baptist:

they hear him and many of them are baptized.

That is how the gospel,

the good news about Jesus,

begins,

with John baptizing and making disciples.

Now baptism is not mentioned again in the gospel.

Not until the very end.

We have to turn

to the very last three verses

of Matthew’s gospel,

and there we find that it ends

with a passage that has some parallels

with this beginning.

At the end of Matthew’s gospel,

Jesus tells his followers

to go out …

and preach to the whole world

and to baptize all people,

to teach everyone about God’s love.

And that is our mission.

To give people

the opportunity to hear the good news of Jesus,

the good news of the kingdom of God

where those in need are blessed.

That is our mission.

To give people the opportunity

to have a religious experience

and to turn their lives around.

We ourselves always need to be open to this,

and we ourselves can sometimes be

the person who helps someone else

– a family member, a neighbour, even a stranger –

to come to that moment in their own life.

And when we do this

we are strengthened by the promise

with which Matthew ends his book:

“Remember,”

Jesus said,

“I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

[pause]

“This is my Son, the Beloved, with whom I am well pleased.”

0 CommentsAdvent 4: 21 December 2025

Readings: Isaiah 7.10–16; Psalm 80.1–8, 18–20; Romans 1.1–7; Matthew 1.18–end.

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

So, here we are.

It’s the Sunday before Christmas.

In just four days’ time it will be

Christmas Day.

We’ve had Christmas music on the radio

for at least four or five weeks;

people putting flashing lights and decorations

outside their houses

since at least the middle of November;

Christmas trees galore.

And the shops, oh the shops …

some of them have been playing Christmas music

since the middle of October!

They’re desperately trying

to get us to part with our money,

or to organise festive parties

and consume more food and alcohol.

But here at All Saints things are

a little … bit … calmer.

Here, it is – mostly – still Advent,

with Advent hymns, and Advent liturgy,

with Advent vestments – Advent purple.

True, we have Christmas greenery around,

and a tree over there,

but the lights are still switched off!

And at home too, our Christmas tree

has only just gone up, on Thursday.

It’s not that I’m a killjoy,

I’m not the grinch

and honestly I do try hard

not to moan too much

about other people starting Christmas so early –

well, I try really hard not to moan in public anyway.

But for me,

Advent has always been important

and I love the rituals and liturgies and hymns of Advent.

But now as we come to the last week,

the last few days of Advent,

the pace quickens

as Christmas comes more closely into view.

So in today’s readings,

we heard Isaiah’s prophecy,

a prophecy of a child,

a child who would be called Immanuel.

Now Isaiah was speaking

hundreds of years before the time of Jesus

when there was still a Jewish kingdom

centred on Jerusalem and ruled over

by the descendants of King David.

In Isaiah’s time

that kingdom was under severe threat

from its neighbours

and with the benefit of hindsight

we know it was going to be destroyed

soon after these words were first heard.

But Isaiah prophesies that there is still

hope.

Isaiah prophesies to king Ahaz,

the successor of King David,

that before a child who is still in the womb

is old enough to choose between right and wrong,

the kings of Damascus and Samaria will fall,

and the threat to Jerusalem will fall with it.

Isaiah gives this unborn child the name ‘Immanuel’,

– God with us –

a sign of hope in the future

and trust in the divine will.

And later generations

would come to see this prophecy

as a promise in times of trouble.

That one day a boy would be born

who would restore the line of King David

and restore God’s laws.

Well, that was today’s Old Testament reading.

And a couple of weeks ago,

on Advent 2,

we heard another of Isaiah’s prophecies.

In that one he prophesies

that a shoot would come from the root of Jesse.

Who was Jesse?

Well, Jesse was the father of David,

the shepherd boy who defeated Goliath

and became the great king of Israel.

Isaiah prophesies

that the line of Jesse will be great again,

and that on this new shoot from Jesse’s root

“The spirit of the Lord shall rest.”

And there are quite a few other places in Isaiah,

and elsewhere in the Old Testament –

verses and prophecies

that Christians came to see

as pointers to Jesus.

Some of them are clear,

and others are picturesque or even pretty cryptic.

But several of these verses

are picked up in a hymn we sang earlier this morning.

Perhaps you’ve already spotted some of them

as I’ve been talking:

- Emmanuel

- Root of Jesse

- Key of David.

Of course, I’m talking about

that hauntingly beautiful Advent carol

“O come, O come, Emmanuel”.

You see, all these verses of the hymn

are addressed to Jesus

to the coming Jesus.

He is the one that the hymn acclaims:

as Wisdom;

as Adonaï – Lord;

as sprung from the root or lineage of Jesse;

and so on.

And it’s particularly appropriate

to sing that hymn in this last week of Advent.

Why?

Well, the hymn derives

from an ancient custom at Evening Prayer.

Every evening we say

the Magnificat, Mary’s Song.

And, rather like at this service we sing

Alleluia to acclaim the gospel reading,

so the Magnificat at Evensong also has an acclamation –

or antiphon as it’s called.

And in the seven days before Christmas

it is these seven verses that are used as that acclamation,

one each evening.

(Though if you are paying close attention

you’ll have noticed that we sang

a version of the hymn with only five verses this morning.

But that’s another story.)

Either way, this last week before Christmas

is just the right time to sing the hymn.

So what, you may be thinking?

Good question – so what?

Well, let’s turn for a moment to today’s gospel reading.

It’s from Matthew’s account of the life of Jesus.

And Matthew quotes

those verses from Isaiah about Emmanuel

that we also heard today.

Look, Matthew explicitly says to us; look,

Isaiah made this prophecy hundreds of years earlier,

and that prophecy is fulfilled … in the birth of Jesus.

It is Jesus who is really this Emmanuel.

And one of the things about Matthew’s account

is that he tells the story of Jesus’s birth

from the point of view of Joseph.

We are more used, perhaps,

to hearing the story from Mary’s perspective –

how the angel Gabriel appeared

and told her she would have a baby

and how she visited her kinswoman Elizabeth

who was also expecting a baby

and so on.

But that’s not what we have here.

Matthew carefully tells us

– in the verses just before today’s gospel reading –

that Joseph is descended from King David.

In fact he gives us quite a long list

of how Abraham’s line leads to David

and the kings of Judah that followed,

and then after the end of the kingdom

the line leads to Joseph,

and so to Jesus.

Joseph, Matthew tells us,

is the heir of King David.

And therefore, Matthew implies,

Jesus too is the heir of King David.

All those prophecies in Isaiah and elsewhere

about the restoration of David’s line

– all those verses in O come, O come, Emmanuel –

Matthew wants his hearers, wants us, to conclude

that they can be seen as references

–prophecies –

to Jesus.

Matthew sees Isaiah’s prophecy

and makes a parallel with Jesus’s birth,

seeing it – like Isaiah –

as a sign of hope and trust in God.

And to us,

the name Immanuel signifies even more.

It tells us …

that God is with us.

That God, the creator of the universe,

lives among us,

lives a human life,

a humble human life,

born to an ordinary family,

in an undistinguished place.

The God that we worship

is not some remote cosmic being,

nor a fickle pleasure-seeking divinity

(such as contemporary Greeks and Romans believed in).

No,

this is a God who puts off

all his divine attributes and status

to live within the limits of a human life

and … a human death.

Just like us.

In the birth and life of Jesus

the human and the divine mingle

in a way that poetry and theology

are better at describing than science.

And in just a few days we shall be,

as it were,

witnesses once again to this mingling,

this incarnation,

as we celebrate the birth of that baby

and ponder its meaning in our hearts.

O come, O come Emmanuel!

0 CommentsLast Sunday after Trinity: 26 October 2025

Readings: Joel 2.23–32; Psalm 65; 2 Timothy 4.6–8, 16–18; Luke 18.9–14

‘The tax-collector, standing far off,

would not even look up to heaven,

but was beating his breast and saying,

“God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” ’

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Back in the 1670s, when Charles II was king,

the heir to the throne was his brother James.

An Italian princess, Mary of Modena,

was chosen to be his wife,

a Roman Catholic, like James.

But it seems that the pope was opposed to the marriage,

so they sought the help of Cardinal Barberini

and he persuaded them to marry immediately.

It would be, he advised,

“less difficult to obtain forgiveness for it after it was done,

than permission for doing it”.1

Cardinal Barberini’s advice

has become something of a proverb,

especially in recent years, hasn’t it?

It’s easier to ask forgiveness (after the event)

than to get permission (before).

And the tax collector in today’s gospel reading

certainly seems to have his eye on forgiveness, doesn’t he?

So what are we to make of this?

Jesus is telling a story about two characters,

one a Pharisee, and the other – a tax-collector.

Now if you’ve been hearing

bible readings and sermons for some time

you’ve probably already got some ideas,

some preconceptions,

about Pharisees, and about tax-collectors.

Pharisees –

well, they’re always arguing with Jesus, aren’t they?

And full of themselves and their strict rules.

And as for tax-collectors,

I suppose we know instinctively

that they’re not particularly nice people,

don’t we?

After all, who likes the taxman

even in our own society?

Most of us probably think we pay

at least a bit too much tax,

and the taxman

– not to mention Chancellors of the Exchequer –

often seems to be trying to take a bit more.

(But perhaps I’ll leave a discussion of

the British tax system for another occasion!

Back to first-century Judea.)

We can see in the gospels

that Jesus does seem to have

something of a soft spot for tax collectors.

We read about Levi or Matthew

being taken from the tax office to be a disciple,

and about little Zacchaeus climbing a tree

to see and hear Jesus,

and then hosting a banquet for him.

These are perhaps typical

of the attitudes we might bring

to a discussion of this parable.

But they are not, I suggest,

what Jesus’s immediate hearers would have thought.

Most likely they would have considered a Pharisee

to be a paragon of virtue,

instructed in the law,

the biblical law,

someone to be esteemed and copied.

And as for a tax-collector …

well, it wasn’t just that he took people’s money;

no, the real problem with tax collectors

was that they were collaborators,

collaborators with the Romans,

the hated occupying power.

If we think what the attitude was

to Nazi collaborators during the War, say in France –

after the War many were lynched,

killed by the mob or executed by the state.

That perhaps gives us an idea

of what the Judeans and Galileans listening to Jesus

might have thought about tax collectors!

And yet Jesus, in this parable,

says it is the tax collector who is closer to God.

Now, we’re coming towards the end

of a three-year cycle of bible readings

at our Sunday morning services,

and over that three years we have heard

a lot of Jesus’s parables.

And one thing that comes across to me

is Jesus’s skill at using just a few words

to conjure up in our imagination

a situation and some characters –

and then to turn it all on its head

and shock his listeners with a surprising outcome.

It’s one of his favourite devices,

a favourite way of teaching and telling stories.

And I’m sure he preached this way

in part to get his hearers to think for themselves.

And Jesus delights in challenging stereotypes,

both positive stereotypes and negative stereotypes.

So, a couple of weeks ago

we heard about the Samaritan leper,

a hated foreigner,

who was healed.

And in this reading today

it is the godly Pharisee who is roundly criticised,

and the hated tax collector

of whom Jesus speaks approvingly.

You can almost hear people in the crowd

muttering to one another

“What does he mean?

How can a tax collector, an enemy collaborator, be good?”

And if we look carefully at the passage in the gospel,

then one of the interesting things

is that actually Jesus does not condemn the Pharisee

for the things that he says he has done,

for his self-discipline and his charity.

He doesn’t condemn the Pharisee for that;

and nor does he condone the tax collector

for what he has done either.

Now in almost the next episode in Luke’s gospel,

we learn about another tax collector, Zacchaeus.

And Zacchaeus, hearing Jesus’s teaching,

declares that he will return overpayments with interest,

and give away half what he has to the poor.

But there is nothing like that here.

Jesus keeps this story

short, sharp and pointed.

Because today’s parable

is not primarily about

the ethics of either the Pharisee or the tax collector,

but about their attitudes:

their attitudes to themselves,

their attitudes to others,

and their attitudes, above all, to God.

Perhaps one of the key words we heard

was when Jesus says that

the tax collector returned home … “justified”.

“Justified”.

What on earth is that about?

Well, “being justified” and “justification”

are words that carry a lot of theological baggage.

They cause debate and division among Christians

and between sections of the Church.

But ultimately it’s about being fit and worthy,

being made fit and worthy,

fit and worthy to stand in the presence of the Almighty.

What Jesus seems to be saying

is that we do not earn that justification

by what we do.

Now, don’t get me wrong.

Elsewhere in the gospels,

Jesus spends a long time

teaching about right behaviour,

about caring for others,

about looking after the weak and the poor

and all who are in need,

regardless of who they are

or where they have come from,

or society’s attitude towards them —

the poor, the hungry, the homeless,

the sick or disabled,

the prisoner, the refugee,

the oppressed and the shunned.

That work is very clearly a gospel imperative,

and Jesus makes it abundantly clear

that in helping those in need

we are helping … Jesus,

we are helping … God.

Instead, in today’s reading,

Jesus reminds us

that in order to come close to God

we need to acknowledge

that we … are not gods,

that we … are not in control of the world:

that we need to stop and to be honest.

To be honest with my-self.

To confront my own faults, my own issues.

In the story,

the Pharisee’s problem

is that rather than recognising his own faults,

he prefers to see himself as better than someone else.

The tax collector, on the other hand,

does not compare himself to others,

but humbly recognises

that he has not done the right things.

And it is that recognition

which should be the start of a journey for him,

and which should be the start of a journey for each of us.

Perhaps the episode of the tax collector Zacchaeus,

just a few verses later,

indicates what should follow that initial recognition of fault –

a whole new way of life …

new life in the kingdom of God.

[short pause]

And a final thought or conundrum

for us to consider.

I wonder if you have spotted

the “Catch 22” in the parable.

Have you?

It’s all too easy, isn’t it,

to find ourselves thinking

“I thank you that I am not like … that Pharisee”?

Because when we do that

then we are being just like the Pharisee in the parable, aren’t we?

“God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

0 CommentsTrinity 16: 5 October 2025

Readings: Lamentations 1.1–6; Psalm 137; 2 Timothy 1.1–14; Luke 17.5–10.

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

“We are worthless slaves;

we have done only what we ought to have done!”

Some words from Jesus in the gospel reading we have just heard.

Well I was in London during the week,

and I happened to be walking from

Westminster Abbey to Lambeth Palace,

when I spotted an interesting monument

on the Embankment at Millbank

that I’d never noticed before.

It’s a 19th-century fountain,

a big covered drinking fountain,

decorated with polychromatic brick or stone,

and it’s called, as I discovered,

the Buxton Memorial.

It commemorates a number of Members of Parliament

who led the 19th-century campaigns

first

to abolish the slave trade

and then

to abolish slavery itself.

And our gospel reading today

presents us with an “interesting” situation,

don’t you agree?

In that second half, Jesus talks about slaves,

and perhaps you found it a bit uncomfortable.

So, hands up if the idea of slavery

makes you uncomfortable –

the idea … of being a slave,

the idea … of owning slaves,

the idea … of trading slaves.

Slaves – that’s … other human beings.

Most of us here – with a few exceptions –

probably don’t consider ourselves

to have any direct link with slavery –

we aren’t descended from slaves,

and we probably aren’t descended

from slave-owners either,

though of course

we might still have benefitted

from institutions and investments

that derive from slavery.

I guess there are one or two exceptions among us,

and plenty of others in our town

and elsewhere around us,

and we can’t talk about slavery

without being sensitive to that

and to the impact it has had

on our friends and their families.

I’m sure that that personal stake makes a difference

to how today’s gospel reading is heard,

and speaking for myself

perhaps I find it too easy

not to worry that much about it.

Nor should we forget that there are people in this country,

probably people here in St Ives,

who are involved in “modern slavery”:

people who are exploited and kept in bondage;

people who exploit others and keep them in bondage.

Having said all that, however,

I want to make two quick points – about Jesus.

First, let’s be absolutely clear:

there is no indication at all

from anything we read in the New Testament

that Jesus or his family

or any of his immediate associates

ever owned slaves.

There are no slaves at his birth in Bethlehem,

and no slaves tending to him in the gospels.

When Jesus visits his friends Mary and Martha,

it is famously Martha

who is busy with domestic chores,

not a slave.

And the second point

is that Jesus isn’t setting out

to overturn the institution of slavery

as it existed in the ancient Mediterranean world –

not in the short term anyway.

That was for later generations –

though he clearly envisaged

a different way of treating everyone,

regardless of whether they were slave or free.

So what are we to make of all this?

Well yesterday

I was licensed by the bishop

to be a lay reader,

a licensed lay minister

in this parish.

And being a minister is also about being a servant.

You see, the word minister comes to us from Latin

and its first use was in the second century

to refer to deacons.

That’s because the word deacon

comes from the Greek word διάκονος2,

which simply means “servant”,

perhaps especially someone

who waits at table.

It wasn’t long before “minister”

came to be used of all clergy –

not just deacons, but priests and bishops too,

(even archbishops-designate)

and also of the lesser orders

such as sub-deacons and readers,

all of whom are servants …

servants of God.

And Jesus makes this point several times, doesn’t he?

In one of the weekday readings

from Morning Prayer last week,3

Jesus reminds his disciples

that the rulers of the Gentiles

lord it over them

and that the great ones of the Gentiles are tyrants.

But his disciples, Jesus says,

his disciples are to be servants;

and he mixes the language of servants and slaves

saying that

“whoever wishes to become great among you

must be your servant4,

and whoever wishes to be first among you

must be slave5 of all”.6

This same story appears also in Luke’s gospel7

only there it has an extra punchline –

“who is greater,” asks Jesus,

“the one who is at the table

or the one who serves?

Is it not,” Jesus says, “is it not the one at the table?

But I,” he answers himself, “I

am among you as one who serves”.

And there’s a version in John’s gospel too8.

There Jesus concludes

by telling the disciples

that just as he has served them,

they are to serve one another.

Just as he has served them,

they are to serve one another.

So let’s come back

to the words in today’s gospel reading:

“We are worthless slaves;

we have done only what we ought to have done!”

In our context,

in the twenty-first century,

we might well see Jesus’s words

as a little harsh,

and for some

a painful reminder

of the slave trade.

But let’s paraphrase those words a bit;

how about this?

“Our role as Christians,

as followers of Jesus and his teaching,

our role is to serve others,

to look after others,

to help others.

That’s what God asks us to do.”

We may be able to serve a lot;

or we may only have the capacity at the moment

to serve a little;

or maybe right now

we are among the ones who need to be served.

But it is this humble service to others

which is at the heart of Jesus’s message

of compassion and reconciliation.

It is the role of ordained ministers

(even of an archbishop-designate);

it is the role of licensed lay ministers;

it is the role of all of us who hear the words of Jesus.

To serve … God;

to serve … each other;

to serve … the whole of creation.

Because we stand today at a crossroads.

Of course, we stand each day at a crossroads,

the junction between the past and the future;

the past behind us,

known, or partly known;

the future before us, largely unknown.

For me, right now,

that crossroads is defined by

my licensing yesterday in the Cathedral,

my licensing as a lay minister

to serve in this parish.

But we each of us stand at a crossroads.

We don’t know what the future will bring,

individually or collectively,

for us or for our parish.

But what we do know is that

every day

Jesus calls us, each one of us,

to serve.

To serve one another,

to serve our community,

to serve the world.

So, finally once again:

“We are worthless slaves;

we have done only what we ought to have done!”

Now Jesus is prone to hyperbole.

He loves to exaggerate for effect,

to grab attention.

And we can see that here.

Sometimes we need support and affirmation.

At other times we need taking down

a peg or two.

(Well I do anyway.)

But Jesus’s message is

a call to serve.

I am, he says, among you as one who serves.

So in the days ahead

I invite you

to take a few moments to think about

what you can do to serve;

what we as followers of Jesus

individually and collectively

can do to serve:

to serve God’s world

and to serve God’s people,

to serve them here in St Ives.

Amen.

Note: at the end of this service it was announced that the Vicar would be leaving in January. Some of the “unknown future” text was written with this in mind.

0 Comments

Holy Cross Day (with baptism): 14 September 2025

Readings: Numbers 21.4–9; Psalm 22.23–28; Philippians 2.6–11; John 3.13–17

Have you noticed

how flying flags

has become so popular this summer?

Even if you haven’t seen any yourself,

well, it’s been all over the papers and the tv news,

hasn’t it?

Here in St Ives there are flags

fluttering from lamp-posts in the town centre,

and plenty more adorning bedroom windows.

If you go further afield

you’ll see them strung along bridges across the motorway

and so on.

Or you might have seen more than a few flags

being carried through the middle of London yesterday.

And of course

they’re not flying just any old flag are they?

They’re either flying the Union Jack,

or perhaps more likely

the flag that’s part of the Union Jack –

the flag of St George.

I’m sure we can all picture that flag:

the white background with a red cross on it.

So, I want to think for a minute –

what does that cross mean?

What does it represent?

Well, one place where you’ll find quite a lot of crosses

is here in this church.

There’s a really big cross,

right up there.

Take a look!

It’s perhaps the most prominent feature

of the inside of the building.

Because the cross is the primary symbol of Christianity.

So much so that it has its own special day each year –

Holy Cross Day,

celebrated year after year on the 14th of September.

Today!

And yet it’s a strange thing to celebrate,

if you think about it.

After all, the cross is an instrument

of torture and death –

that’s what’s going on up there, isn’t it? –

and a similar symbol in our own society might be

a hangman’s noose perhaps.

Don’t you think it’s rather shocking to celebrate that?

It certainly ought to be shocking;

it ought to bring us up with a start.

The cross is a symbol of the death of Jesus.

And the death of Jesus

is an event of supreme significance.

You see, when Jesus died on that cross,

he died (just as he had lived),

proclaiming … forgiveness,

proclaiming … reconciliation,

proclaiming … God’s love for everyone.

Jesus in his life and ministry

had told his listeners

that what he called “the kingdom of God” was at hand –

the ability to live without hate, without selfishness,

but with love and compassion.

For those we agree with, yes –

and also towards those we don’t.

Because forgiveness and compassion

are the message of the Cross,

of Jesus on the Cross.

Jesus’s message isn’t about condemnation –

what was that line

in today’s gospel reading?

“God did not send [Jesus] into the world

to condemn the world,

but in order that the world might be saved through him.”

Forgiveness and compassion.

We know that forgiveness and compassion

aren’t always easy.

But Jesus on the Cross teaches us

that forgiveness and compassion

are the way to end … hatred,

the way to end poverty,

the way to end violence.

And even, yes,

even the way to end the political assassinations

and school shootings that we see in the news.

Forgiveness and compassion.

The message of the Cross,

embodied in that red cross

on the flag of St George and the Union Jack,

is one of radical inclusion and radical hospitality.

It lives “in the words we choose,

the causes we defend,

the way we treat one another.”9

Wouldn’t it be wonderful

to think that this is the message

that is shared by those

who are putting up flags in our streets?

Or do they want it to symbolize …

exclusion?

But back to Jesus:

in his death on the Cross

Jesus brought that kingdom, God’s kingdom, into being.

Now sometimes you’ll see a cross

with the figure of Jesus

not naked and suffering,

but in royal robes and crowned –

Jesus Christ,

“lifted up” (as our gospel reading just said)

lifted up and reigning from the cross.

That image is a theological statement of course,

and it reminds us that his suffering and death lead …

to the hope of resurrection and new life,

a new life where we are able

to set aside

the powers and temptations that lie all around us

and even within us,

the things that make us selfish –

and instead to live,

here, now,

in God’s kingdom of goodness and love.

You see,

God invites each one of us,

you and me,

to make that choice,

that personal commitment,

to try and live that new life.

And that leads me on …

Because

we are also here today

to celebrate, to celebrate a baptism,

the baptism of little N.

And a baptism is always an occasion for celebration.

When it’s a baby being baptized

it’s a wonderful opportunity

to celebrate the birth of that new life,

a new child into a family,

and I’m sure N’s family

are definitely going to have

that celebration a bit later.

We all love a party and we all love a baby!

And of course baptism is so much more

than an excuse for a party.

You see,

at baptism we enter a new life

as we become a member of the Church,

a member … of God’s family.

First, the person being baptized makes some promises.

Or if it’s a baby or small child like N today,

the parents and godparents

make these promises on N’s behalf.

They promise to try and live in God’s way,

rather than the way of the world:

to try and live in love and hope

and to reject the influences and ideas

that want so hard

to drag us back to the world we know so well,

the world of selfishness, envy and jealousy,

prejudice and hate.

And the cross plays a significant part in the baptism service.

We’ll see in a few moments

that Fr Mark will trace a small cross on N’s forehead,

anointing her with oil,

and then invite her parents and godparents

to trace that cross on her forehead

with their own thumbs too.

Because

all Christians are marked with the Cross.

Or perhaps I should put that the other way round:

the Cross marks us.

The Cross marks us out

as people who try –

people who try … to follow Jesus,

who was loving and compassionate.

And who cared for every person,

especially for those in need.

N, if your parents and godparents

remember and teach you that,

then you’ll be doing okay.

A new life is a wonderful thing.

And a new Christian,

a new member of the Church,

is a wonderful thing too.

I pray N

that as you grow

you will be full of love and compassion,

someone in whom all can see

the true mark of the Cross.

Amen.

0 CommentsSt Peter and St Paul: 29 June 2025

Readings: Acts 12.1–11; Psalm 125; 2 Timothy 4.6–8, 17, 18; Matthew 16.13–19

May the words of my mouth

and the meditation of my heart

be acceptable in your sight, O Lord.

I wonder if you’ve ever been to Rome.

It’s somewhere I’ve been several times,

and one of the things I have done each trip

is visit the Vatican

and climb up the dome of the great basilica there.

It’s a bit of a slog,

some 500 steps to the top,

but when you get up there

you are rewarded

with some wonderful panoramic views across the city.

And you can also access the gallery

that runs around inside the dome.

From there

you get some really impressive views of the interior.

One thing you can see close up, for example,

is a Latin inscription

that runs full-circle around the dome.

In giant lettering it begins: “Tu es Petrus …”.

I’ll come back to these words in a moment.

– if you’re not too bothered about the height –

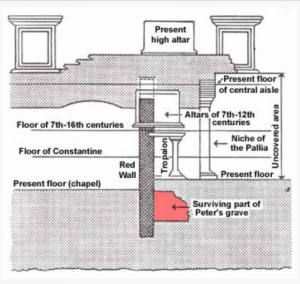

perhaps you can look straight down.

It’s a rather dizzying couple of hundred feet

but there beneath you

is the high altar,

with its great baldachino or canopy by Bernini.

And right in front of that altar

there’s a semi-circle of steps

leading further down,

down beneath the floor of the church.

Now these steps aren’t accessible to the public.

But if you could go down them,

and under the high altar,

you’d find yourself

standing among the remains

of an ancient Roman cemetery.

Because those steps take you down

to the site of the tomb of St Peter.

Of course, the church we see today

was completely rebuilt

some 4 or 500 years ago,

in the flamboyant baroque style.

But they rebuilt it

on exactly the same site

as the previous church,

with the high altar

in exactly the same place as before.

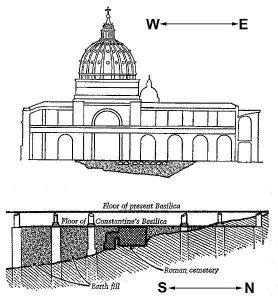

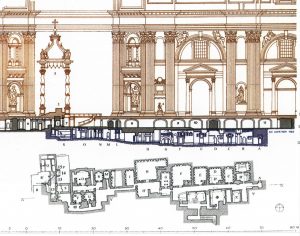

Section showing the various altars and floor levels and their relation to the tomb of St Peter. [Liturgical Arts Journal]

over a thousand years earlier,

in the 300s,

as soon as Christianity had been legalized.

It was built

– with considerable difficulty –

right on top of this ancient Roman cemetery;

and awkwardly,

on the side of a hill;

all carefully positioned

so that the high altar

was directly over

one particular tomb*.

And next to this cemetery

there had been an arena,

the Circus of Nero,

and that’s where many early Christians

had been put to death,

accused by Nero

of causing the great fire of Rome.

Peter himself was among those executed,

said to have been crucified

– crucified upside-down according to tradition.

Paul was a Roman citizen though,

so he was spared crucifixion

– he was beheaded

(and buried)

elsewhere in the city.

Other Christians were rounded up

and put to death in the arena:

torn apart by wild beasts,

or forced to fight to the death as gladiators,

burned alive,

or killed in some other barbaric Roman spectacle.

And it is

this first great persecution

– the martyrdom of Peter and Paul and many others –

that we are remembering today.

It is those martyrs, Peter, Paul and the others,

that we commemorate

and hold in great honour.

It was probably around the year 64,

so just 30 years or thereabouts

after Jesus had walked around Galilee

and come to Caesarea Philippi.

And we heard a bit about that

in today’s gospel reading.

Peter,

Simon Peter,

at Caesarea Philippi

acclaiming Jesus as the Messiah.

You can sort of imagine him blurting it out, can’t you?

The first person to put into words

what he, and perhaps others,

had been thinking.

And Jesus recognizes the leap that Simon Peter has made.

This is when Jesus gives him the nickname:

“Rock”, which of course is what “Peter” means.

“You are the rock,”

he says to him

– “you are Peter”.

Remember that inscription around the dome at the Vatican?

This is the verse that it quotes, in Latin:

“Tu es Petrus”, “you are Peter”.

And in the 30 years or so

since that moment at Caesarea Philippi,

first Peter, the rock, and then Paul

had built the early church

from tiny beginnings

to something that was starting to be noticed

– even in the heart of the Roman Empire.

Because these Christians were a bit different

from your everyday Roman.

They didn’t join in things

that good Romans were supposed to do,

like … sacrificing at the temples,

or considering the emperor to be a god.

And although a few of them were wealthy,

many were slaves or ex-slaves

or very definitely among the poor and oppressed.

Because it was often among

the poor and the oppressed

that Peter and Paul

and others

preached the good news of the kingdom of God.

“Blessed are the poor, the hungry,

the sick, the persecuted”

Jesus had said

– that’s definitely good news when you are poor and oppressed.

Perhaps this message of hope

(and – dare I say it? –

social revolution?)

was already causing a stir in Roman society.

There must have been something they were doing

that attracted the attention of the ruling class

– of the Emperor Nero,

when he was looking for someone to blame

for that disastrous fire.

And I wonder to what extent

this message of hope

– and social revolution –

can still cause a stir in our modern society.

Or have we made it so bland,

or so other-worldly,

that it simply doesn’t impinge

on the thoughts of our fellow citizens?

Most of them have not just given up believing,

they have even given up disbelieving

– they just don’t care.

But as Christians

it is our job to care.

Peter and Paul,

as we have heard,

were martyrs,

a Greek word meaning witnesses.

In their life

and

by their death

they and others were witnesses:

witnesses to the reconciling love of God,

witnesses to the good news

of the rule of God that Jesus had proclaimed.

And just like Peter, just like Paul,

we too are witnesses.

We are God’s witnesses

here in St Ives in 2025.

We are the ones

tasked with representing God –

representing God

to the world in which we live.

We are the ones

who are called to bear witness

to what God has done in our lives.

To bear witness

to what Jesus means in our lives.

Now I trust and hope that none of us

will be called to bear witness

in the face of persecution and violent death.

So we will not be martyrs

in the way that the word is used nowadays.

We will not be martyrs like Peter and Paul.

But we can be God’s witnesses

among our friends and family,

our acquaintances and colleagues,

and those we meet.

Does that sound a daunting task?

Well, maybe it does, yes!

So, let’s start with something

any of us can do.

Let’s think for a moment.

Do you have a ready answer

when someone asks

what do you do on a Sunday morning?

Do you have a ready answer

when someone asks why do you go to church?

Do you have a ready answer

if someone asks you about Jesus?

If I’m honest, I’m not sure I do.

So my challenge to each one of us is this:

find time this week to spend a few minutes

considering how you would answer those questions

– in just a short sentence or two.

How you might answer those questions

in a way that encourages engagement and further interest.

And little by little,

person by person,

we will,

like Peter and Paul

and all the saints before us,

help to build God’s kingdom

here on earth

as it is in heaven.

Amen.

* This is a slight over-simplification. In the first Church, as originally built under Constantine, the tomb was visible. It was Gregory the Great (in about 594) who raised the floor of the sanctuary by several feet and placed the altar over the tomb. That altar was at a level several feet below the floor of the rebuilt basilica that we see today.

0 Comments

Nicaea and the date of Easter

This article was first published in the June 2025 issue of Transforming Worship News (formerly Praxis News of Worship).

The date of Easter is often regarded as rather complicated, too complicated for nearly everyone to worry about. But it links us with the origin of the annual festival, and the way the early Church celebrated the resurrection.

When the Emperor Constantine decided that Christianity was the best hope of unifying his empire, he found disagreement on several topics, including the nature of Christ and the date on which to hold an annual celebration of his resurrection. The Council of Nicaea in 325 attempted to resolve both issues, agreeing a statement of belief and formalizing the date of Easter.

The story begins with the Jewish festival of Passover, held at the first full moon of the spring, when the moon lights the sky all night. In the Jewish lunar calendar this day is 15 Nisan, and the previous day, 14 Nisan, is the day of preparation. In the late afternoon of that day, until the Temple was destroyed, Passover lambs were slaughtered in the Temple precincts. They were then roasted and eaten at the Passover meal that began with the full moon at sunset, the start of 15 Nisan. In the fourth gospel, the crucifixion was on 14 Nisan, and in the synoptics on 15 Nisan.

There is no explicit evidence in the New Testament of a yearly Easter. The focus in the early Church was the weekly celebration of the resurrection on the first day of the week, every Sunday. Although it is not entirely clear – and there may have been a cover up – it seems that Christians in Jerusalem and the Jewish diaspora did keep an annual festival, but Gentile Christians probably didn’t. The former group kept an annual celebration of both the crucifixion and resurrection on 14 Nisan, whichever day of the week that fell on.

Perhaps influenced by this annual feast kept in the diaspora, other Christians began to observe it and a fast on the previous day. But rather than keeping it on 14 Nisan they celebrated the following Sunday, the day of the weekly commemoration of the resurrection. Perhaps just as today, it was more convenient to transfer weekday festivals to Sunday.

These two groups co-existed until at the end of the second century, Pope Victor I controversially excommunicated those who kept 14 Nisan – the Quartodecimans (or “fourteeners”). A century later the dispute had not ended although the Quartodecimans were a distinct minority. So when, commanded by Constantine to agree a common date, the bishops assembled at Nicaea it was not surprising that majority opinion, favoured by Rome and other major sees, prevailed. The Council ruled that the annual paschal feast, celebrating the resurrection, should be observed on the Sunday after the first full moon of the spring, the full moon after the equinox.

The Council did not prescribe how this might be determined in advance, and initially it was perhaps left to direct observation. Competing tables of dates soon emerged, frequently based on a 19-year lunar cycle that had been known since at least the Babylonians. The date of the equinox, which in the first century had fallen on 25 March, had by the fourth century drifted to 21 March. Tables from Alexandria were generally regarded as the best, and the declaration each year from that see of the date of Easter was usually followed, though for many years the see of Rome used different tables so occasionally Easter would fall on another date. Eventually the tables compiled and extended by the sixth-century monk Dionysius Exiguus were accepted as definitive. These continued in use throughout the Church, across the schism between East and West. As the middle ages wore on it was recognised that both lunar and solar components of the tables were increasingly inaccurate, but it was not until after the Reformation that Pope Gregory XIII unilaterally introduced a modified calendar with self-correcting lunar tables. Although these were gradually accepted by the churches of the Reformation they have not been adopted in the East, at least not for determining Easter.

In the twentieth century there were some moves to fix the date of Easter, but at the end of the century the World Council of Churches proposed abolishing calculated tables based on the approximate 19-year cycle and instead using accurate astronomical calculations of the equinox and the full moon as observed in the time zone of Jerusalem. They suggested this might be adopted in 2000 when both Eastern and Western calculations coincided on the same date. There was some support for this from Rome, from Anglicans and various churches of the Reformation and some Orthodox churches, but it was far from universal. In this 1700th anniversary year of Nicaea, when Easter dates again coincide, the WCC has re-iterated its proposal. Once again, it seems unlikely to gain enough support to be brought in.

Simon Kershaw remembers trying to calculate Easter from the tables in the BCP while enduring long sermons as a young chorister at Evensong. He has continued to calculate and write about the date of Easter.

2 CommentsAscension Day: 29 May 2025

Readings: Acts 1.1–11; Daniel 7.9–14; Psalm 47; Ephesians 1.15–23; Luke 24.44–53

May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart

be acceptable in your sight, O Lord.

Did you ever watch I, Claudius?

Or perhaps you’ve read the books?

I suppose I was about 15 when I first read them,

shortly before the BBC made that wonderful adaptation.

Remember – Derek Jacobi in the title role,

and a host of other stars?

I well recall our Latin teacher back then

telling us that the books were so good

that occasionally he would forget

whether some incident was actually historical

or had instead been invented by the author, Robert Graves.

And certainly Graves did include

a host of real historical information in the books.

For example, Graves relates

that a few weeks after the emperor Augustus died in AD 14,

the Roman Senate declared him to be divine.

They built an official state temple,

and special coins were minted

showing the emperor being carried up to heaven,

perhaps in a chariot,

accompanied by wing’d figures.

So you see there’s some history

of great rulers being declared gods

when they died

or even whilst still alive.

And a few years after Augustus,

around AD 40,

the emperor Caligula declared himself a god.

Claudius was next,

declared divine immediately he died in 54.

Even his nephew, the infamous Nero

who ruled until 68,

was worshipped as part of the divine imperial family.

I’ve mentioned these dates,

not to try and give a history lesson

– there’s no exam later –

but because they remind us

that this is exactly the time

when the events of the New Testament took place

and when much of it was written.

This is the context

in which Jesus was first proclaimed by Christians

as the Son of God,

and described as being taken up into heaven.

We might well wonder what the relationship is

between the descriptions of Jesus’s ascension

and the tradition of emperors and others

taken up to a pagan heaven.

Let’s think about what we heard earlier in our readings.

The Old Testament lesson from Daniel draws on traditions

several hundred years before those Roman emperors,

Claudius and Co.

It’s a vision of a human figure

“coming with the clouds of heaven”,

coming to the throne of God and receiving eternal kingship.

Clearly Jesus’s ascension sits in this tradition.

And we also had two accounts of that Ascension of Jesus.

Our service began with the opening words of the Acts of the Apostles.

It’s rather the definitive account,

the one we think of when the Ascension is mentioned.

And our gospel reading had the ascension story again,

this time from the very end of Luke.

Did you notice any differences between these two –

one from Acts and one from the gospel according to Luke?

Did you?

Because they aren’t quite the same.

In the gospel

the Ascension happens at the end of Easter Day itself,

but in Acts it’s forty days later,

just as today is forty days after Easter Day –

remember I said it’s the Acts account we generally recall?

And it’s only in Acts that

“two men in white robes” appear

and explain to the disciples what’s happened,

telling them Jesus will return in the same way.

Now don’t forget Claudius and those other emperors.

I’ve suggested that the New Testament descriptions of Jesus’s ascension

have a parallel

in the contemporary Roman emperors being declared divine.

But at the time, of course,

the stories of emperors were much better known

than the story of Jesus.

Whatever it was that the disciples witnessed,

what they are doing is asserting a cult

that is a rival to the official cult of the Roman state.

A cult, a religion, in which their leader

mystically ascends into the heavens in recognition that he is divine.

And of course the disciples, the early Christians,

assert that it is their story which is true,

and that the divinity of the emperors is bogus.

They use the well-known stories about emperors

to proclaim the truth about Jesus.

So what is it that they are trying to say?

Let’s consider two important things.

First

these early Christians were absolutely convinced that Jesus was divine.

They hadn’t yet worked out the theological details,

but there’s no doubt that they had become convinced it was true.

They want the world to hear about Jesus;

and

they want the world to hear

that Jesus is divine.

And secondly:

what do the passages say?

“you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem … to the ends of the earth”

(that’s Jesus in Acts)

and “repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed …

to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem”

(that’s from Luke).

And this is surely the key lesson for us.

You’ve heard me say it before

and I make no apology for saying it again.

The task that Jesus gives his disciples

is to tell everyone the good news about the kingdom of God.

We are to tell people about our hope:

hope in the reconciliation that is God’s love –

hope in reconciliation with God the creator

and

reconciliation with God’s creation, with all our fellow creatures.

Reconciliation with God the creator

and reconciliation with our fellow creatures.

What does that mean in practice? What can we each do?

It means living at love and peace

with our family and our neighbours,

not getting into disputes, not bearing grudges

– “forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us” –

and this applies to every aspect of our lives:

to personal conflict,

to local and regional conflict,

to international conflict.

And it applies to issues of social justice as well:

to equitably sharing the bounty of this world –

food, housing, healthcare,

fair employment and fair wages,

ending unjust discrimination.

And to our stewardship of the world that we are called to live in.

It isn’t always easy, is it?

But all this flows directly

from Jesus’s message of love and reconciliation.

This is Jesus’s manifesto of compassionate love.

What any one of us can do

may be quite limited,

but it isn’t zero.

In our personal lives,

in our support for charities, for campaigns,

in how we shop,

how we vote or support political parties,

in how we speak and how we act,

we each of us make

a small but significant impact.

And one final thought.

We’re not alone.

Church is the community of people committed to doing this together.

Here should be the primary community

where we care for each other,

and where we are strengthened for that service in the world,

strengthened by each other

and strengthened by our belief

in the God who loves and reconciles.

Collectively we help advance the kingdom of God,

where God’s love and compassion are shared with all,

and peace and justice flow like a river.

Amen.

0 Comments4 before Lent: 9 February 2025

Readings: Isaiah 6.1–8 [9–13]; Psalm 138; 1 Corinthians 15.1–11; Luke 5.1–11

May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart

be acceptable in your sight, O Lord.

Over the last few weeks,

since the start of January,

we’ve been listening each Sunday

to stories about the beginning of Jesus’s ministry.

How Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist;

and about the wedding at Cana,

where ordinary water was turned into abundance –

an abundance of the best possible wine.

We heard how Jesus came to Nazareth

and himself read the passage

where Isaiah foresees

good news for the poor and the oppressed,

for the blind and the captive.

And today we have Jesus

gathering his first disciples.

In Luke’s account,

which is what we are mostly reading this year,

this is the first time Andrew, James and John have appeared,

though Simon Peter gets

a teensy mention in the previous chapter.

And yet they do exactly what Jesus says.

What’s going on?

Luke doesn’t really tell us,

but we can get a hint from John’s gospel.

You see, John tells us

that Andrew was a disciple of John the Baptist;

that when Jesus was baptized

John the Baptist pointed him out to Andrew,

and Andrew then went and fetched his brother Simon Peter

and introduced him to Jesus.

Another disciple with Andrew is not named,

but it is traditionally thought to have been John –

that’s the same John who was one of the fishermen

in today’s story,

the brother of James.

So it seems Jesus already knew these four fishermen,

Andrew and Simon Peter, James and John.

But they had not yet begun to travel around with Jesus.

What changed?

Well,

what changed

was that John the Baptist had been arrested by Herod

and was now a captive in Herod’s dungeons,

where he would soon be executed.

Can you imagine what it must have been like

for those who had flocked to hear him preach

and become his disciples?

It must have been a dark and difficult time, mustn’t it?

Well, the gospels don’t tell us anything

about what happened to John the Baptist’s followers

when he was arrested –

but it’s easy to imagine, I think, that they all ran away,

away from the danger that they too

might be identified with his movement

and his criticism of Herod.

Away from the danger

that they too might be arrested and perhaps put to death.

That they ran away

back to the anonymity of their homes

and their families and their everyday jobs.

And that’s where we find

Andrew and Simon Peter, James and John –

back in their family businesses of catching fish

and no doubt trying to keep a low profile.

And then – Jesus comes back too.

Perhaps he’s realized that his time has arrived:

that with John the Baptist silenced

it is his turn to proclaim the word of God,

to proclaim the good news about the kingdom of God.

And already people are listening to him:

Luke, in our reading today,

says “the crowd was pressing in on him”.

Why?

Luke tells us they wanted “to hear the word of God” –

Jesus preaching about the kingdom of God.

And in this mêlée,

there right in front of Jesus

are some people he knows:

Andrew and Simon Peter, James and John.

Was he looking for them?

Or did he just come across them?

What he saw though was an opportunity

to stop the crowd pressing in on him

and to continue to teach from the safety of a boat,

presumably just out in the shallows.

And then

they put down their nets

and catch fish –

fish in great abundance,

fish almost beyond their capacity to bring to shore.

And this miraculous catch of fish

provided the perfect opportunity

for Jesus … to tell a joke.

To me that’s one of the things

that comes across so strongly

in the gospel stories about Jesus.

He was just the most wonderful speaker –

a really skilled orator.

Jesus knows when to tell a story and when to argue;

he knows when to cross-question and when to debate;

and he knows how to use

exaggeration and sarcasm and humorous one-liners

to great effect.

And that’s what he does here, isn’t it?

“Yes, you can carry on catching dead fish,” he says,

“or you can come with me and we’ll fish for living people.”

Of course it’s not just a one-liner –

the punchline to the teaching about the kingdom of God

they have just heard him deliver,

or the punchline to the great catch of fish

they have somehow just managed to land.

No, it’s not just a one-liner,

it’s also a prophecy, isn’t it?

Because we know that’s exactly what these fishermen,

these ordinary people,

will become.

They start right here

becoming Jesus’s first disciples.

They will finish,

beyond the end of Luke’s book,

bringing in a miraculous catch of people,

followers of Jesus in great abundance.

They were frightened fishermen

who had run away

when John the Baptist had been arrested,

and they would do so again when Jesus is arrested.

And yet

Jesus inspired them and nurtured them

and gave them what it takes

to be catchers of people,

miraculously so,

fearlessly proclaiming the kingdom of God’s abundant love.

Here we see the very first steps of that journey,

Jesus gathering together

this group of John the Baptist’s disciples,

who become the core of Jesus’s own disciples.

And it’s a journey that has continued

down the ages and across the world,

right down to us,

to you and to me,

here today in this place

far from the shores of the Sea of Galilee.

Because it is our responsibility now.

We are the disciples sitting on

– if you like –

the beach.

We are the disciples

who have heard Jesus’s message about the kingdom of God –

where the hungry are fed and the homeless housed,

the sick nursed and the stranger cared for,

the oppressed and the persecuted set free,

and where peace and reconciliation

replace bitterness and war.

And our job,

our job is to share this good news,

to live as people who believe this good news

and to invite our friends and our neighbours

to come and live it

and to share in its great abundance.

Thanks be to God.

0 Comments

Counting Sixes in Steadman

Steadman Triples has long been one of my favourite methods to ring. I have previously looked at how the method is constructed of sets of six blows, and how to keep track of “quick” and “slow” sixes. I’ve also learnt to call simple touches of Triples, with calls labelled “Q” and “S”. But more complicated touches use a different notation: the blocks of six blows that make up the method are consecutively numbered, and the sixes in which bobs and singles are called are noted. Alternatively the count is of possible calling positions, since a bob or single may potentially be called at the fifth blow of any six, and the caller needs to know which of these positions to actually call.

The challenge then becomes one of counting sixes – with 100% accuracy. Whilst simultaneously counting your place and keeping track of quick and slow sixes. For me this is brain overload, and I cannot accurately keep all this information in my head. The main problem is that I am trying to keep track of two numbers: my place, and the number of the six. And in the first seven sixes these numbers will be in the same range of 1 to 7, so there is an extra risk of confusing which is which, or incrementing the wrong one, and so on.

What then to do? The first thing is – for the moment – to let other people call touches, while I get my head around the counting. And the breakthrough in being able to count sixes has been the realization that I don’t actually need to count my place: I can pretty much ring Steadman by rhythm and by knowing its structure.

First, then, the rhythm. Dee-dah, dee-dah, dee-dah. That’s the six blows that make up the Steadman unit: handstroke, backstroke, handstroke, backstroke, handstroke, backstroke. Dee-dah, dee-dah, dee-dah. So, if you are double-dodging 4–5 up, that would be (4th, 5th), (4th, 5th), (4th, 5th). If you have just gone down to the front three as a slow bell then it’s (3rd, 3rd), (2nd, lead), (lead, 2nd). In each case I have bracketted the handstroke-backstroke pairs, each of which is a dee-dah.

And then the structure. Steadman work is divided inro two parts. Above third place you double dodge out to the back and then back down again, and into the front three. Each double dodge is one six. If you are on the front then you plain hunt for six blows, then change direction and hunt for the next six blows and so on. If you are in 3rd place at the end of a six then you go out to 4th place and start double-dodging. And you have to know whether to start the front work by plain hunting right (a quick six) or wrong (a slow six) – I’ll come to that in a moment. In the back of my mnd while ringing on the front is the superimposed structure of the slow work – the whole turns and half turns – and these reinforce what I am ringing, but at any given point it’s just plain hunting on three, changing direction after six blows. And the six blows felt rather than counted. Plain hunting on three is sufficiently simple that it can be done without counting my place.

On top of this ringing I am trying to count the sixes. At each handstroke, more or less, I think “this is number n”, or just “this is n”, deliberately saying it to myself in a way that I am less likely to confuse with my place. Steadman begins part way through a six, so the first two blows, right at the start, handstroke and backstroke, are the last two blows of the first six, and sixes continue after that. A plain course of Steadman Triples will come round four blows into the 15th six, while a touch with two Q and two S bobs is twice as long, coming round at the fourth blow of the 29th six.

As for keeping track of quick and slow sixes, that is implicit in the count. A six with an odd number (1, 3, 5, 7 …) is quick, and a six with an even number (2, 4, 6, 8 …) is slow. It just needs a tiny bit of extra brainpower to work this out on the fly.

0 Comments