learning London Surprise Major

Having more or less successfully rung a Plain course of Bristol Surprise Major last weekend, it’s time — like Dick Whittington — to turn to London: London Surprise Major, that is. London is the last of the “standard eight” Surprise Major methods, and Coleman describes it as the zenith of standard surprise. But he also suggests that it is easier to learn than Bristol, and strongly recommends learning it by place bells. Other London web pages seem to agree, one suggesting learning pairs of place bells together, as in each pair one is the mirror of the other.

The order of the place bells is the same as for Rutland and Bristol: 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 6, 4; with the pairs being: 2 and 4, 3 and 6, and 5 and 8; while 7 is symmetric about the half-lead end.

There are a few familiar pieces of work:

- Stedman whole turn, which occurs only on the front

- fishtails, which occur at the back (8–7‑8), and also both ways in 5–6 — 6–5‑6 and 5–6‑5

- plain hunting below the treble — but plain hunting “wrong”, i.e., leading with backstroke then handstroke (“back and hand”) rather than handstroke then backstroke (“hand and back”)

- treble-bob hunting above the treble, sometimes “right” and sometimes “wrong”

When you meet, or are about to meet, the treble you have to get back into phase with it, either to pass it, or to dodge with it. You do this by making a place, or by doing a Stedman whole turn, or doing fishtails.

Another point to note is that the 4th-place bell and above all start in the opposite direction compared with most methods learned so far. So even bells (≥4) go out, and odd bells (>4) go in. The 8th-place bell strikes an extra blow at handstroke in 8th place before going down.

Other than that it seems that the only way to learn this is by place bells, which we do in the full article.

1 CommentBristol Surprise Major: the plain course and bobs

Armed with a continuous blue line, as described in the previous post (but see also this later post), we can write this more compactly as a single lead:

12345678

21436587

12346857

21438675

24136857

42316587

24135678

42315768

24351786

23457168

32541786

35247168

53427618

35246781

32547618

23456781

24365871

42638517

46235871

64328517

46238157

42631875

24368157

23461875

32416857

23146587

32415678

23145768

21347586

12435768

21345678

12436587

14263857

We can also write out what happens when “bob” is called. The front two bells are unaffected, and run in and out as in a plain course to become the 2nd and 3rd place bells. The bell in 4th place, which would have run out to 5th and become the 5th place bell, instead makes the 4th-place bob and becomes the 4th place bell. The bells above 4th place each dodge back one place, which brings them back to their starting positions, so that they simply repeat the same lead as they have just done. Like this:

23145768

21347586

12435768

21345678 bob

12436587

14235678

The bob permutes the 2nd, 3rd and 4th place bells. If called at the end of each of the first three leads this will bring the touch back to rounds – three leads of Bristol.

5 Commentslearning Bristol Surprise Major

[Edit: Although I learnt Bristol Surprise Major in the way described in this post, I subsequently figured it out in what is to me a much more convenient way. You may find it helpful to read this post on the structure of Bristol Surprise Major instead. I think it’s much simpler. You may or may not agree.]

It’s been a long time since I wrote here about learning a Surprise Major method. In the intervening period I’ve learnt to ring six such methods: Cambridge, Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Superlative, Rutland and Pudsey. These are six of the so-called “Standard Eight” Surprise Major methods, and in many ways they are quite similar to each other — Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Superlative and Rutland are all the same as Cambridge when you are above the treble [edit: this isn’t true of Superlative], and Pudsey is the same as Cambridge when you are below the treble. The other two SM methods in this Eight are Bristol and London and they are different from the others, and from each other. Several times I have sat down to learn Bristol, but not got very far. Time to put that right.

So I’ve spent an hour or so looking at the “blue line” for Bristol, as well as a couple of guides. From it I can see that:

- Bristol is a double method, so that once you have learnt a quarter of it you should know all of it

- There are basically three or four pieces of work that you need to learn in that quarter; I call these:

- the “frontwork”, though you also do this at the back

- “Stedman” and “fishtails”

- “lightning work”

I’ll look at each of these in turn.

First we’ll look at fishtails. These are single blows where you reverse direction after each blow, so on the front it might be: lead, 2nd, lead, 2nd, lead:

x-

-x

x-

-x

x-

Next, the frontwork. Bell 2’s work consists of doing half the frontwork one way, and then mirroring it to do it the other way:

- dodge 1–2 down with the treble

- lead right

- fishtails

- lead wrong

- out to point 4ths

- lead right

and then do the same thing in the opposite direction:

- out to point 4ths

- lead wrong

- fishtails

- lead right

- dodge 1–2 up with the treble

(And then, instead of making 2nd place over the treble, go out to 3rd place and become the 3rds place bell.)

Then there’s “Stedman”. This is like a whole turn in Stedman: lead two blows, point 2nd, lead two blows. As in Stedman, one of the pairs of leading will be right (i.e. handstroke followed by backstroke), and one will be wrong (i.e. backstroke followed by handstroke). But in Bristol this doesn’t just occur on the front. It’s also done in 4ths — 4th, 4th, 3rd, 4th, 4th. And because Bristol is a double method it appears at the back (8th, 8th, 7th, 8th, 8th) and in 5th place (5th, 5th, 6th, 5th, 5th). Each of these pieces of work occur twice, once with the first two blows right and the last two wrong, and once with the first two wrong and the last two right.

Armed with this information we can write out what bell 3 does:

- dodge 3–4 up

- 4th place

- dodge 3–4 down with the treble

- an extra blow in 3rd place

- Stedman on the front

- out to 4th place

- Stedman in 4th place (4th, 4th, 3rd, 4th, 4th)

- plain hunt down to …

- fishtails on the front (2nd, lead, 2nd, lead, 2nd and out)

- dodge 3–4 up

- out to 5th and become 5ths place bell

We’re nearly there, and all that remains to do is to look at the “lightning work”:

- hunt out to the back

- one blow only at the back, then turn around and

- hunt down with

- two blows in 5th place

- two blows in 4th place

- down to the lead

- one blow only in the lead, then turn around and

- hunt up to 6th place

This path crosses the treble as it does the places in 4th and 5th:

--x-----

---x----

----x---

-----x--

------x-

-------x

------x-

-----x--

----x---

---1x---

---x1---

---x----

--x-----

-x------

x-------

-x------

--x-----

---x----

----x---

-----x--

That crossing point is also one of the pivot points of the method, i.e. the point where you move from doing things on the front to doing things on the back, or where the blue line rotates through 180 degrees.

Bell 5 begins with the lightning work as described above (the first three blows in the diagram are of course the last three blows of bell 3’s work).

After this point we repeat the work already described, but as places from the back, rather than places from the front. This enables us to write out a complete plain course, as is shown in the full article.

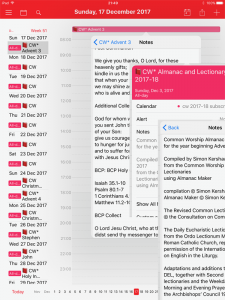

2 Comments2017-18 Almanac for Common Worship and BCP

Once again my annual Almanac, or calendar and lectionary, is published.

Each year since 2002 I have produced a downloadable calendar for the forthcoming liturgical year, according to the rules of the Church of England’s Common Worship Calendar and Lectionary, and the Book of Common Prayer.

The 2017–18 Almanac is now available for Outlook, Apple desktop and iOS Calendar, Google Calendar, Android devices and other formats, with your choice of Sunday, weekday, eucharistic, office, collects, Exciting Holiness lections, for Common Worship and BCP.

Download is free, donations are invited.

0 CommentsPrayers for Manchester

The Liturgical Commission has received a number of enquiries today in the wake of yesterday’s events in Manchester, asking for resources for vigil services. In addition to the prayers tweeted by the Church of England Communications team, by a number of dioceses and by other individuals, the links below to the Church of England website give a number of appropriate prayers for the world/society here https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/topical-prayers/prayers-for-the-world.aspx.

and for individuals here https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/topical-prayers/prayers-for-personal-situations.aspx.

For those needing a complete order of service, pp. 443–448 of New Patterns for Worship has an outline headed “Facing Pain: a Service of Lament” — also downloadable from here https://churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/texts/newpatterns/sampleservicescontents/npw18.aspx

Some of the ‘Cross’ and ‘Lament’ (possibly also ‘Living in the world’ and ‘Relationships and healing’) resources from New Patterns for Worship might also be appropriate for inclusion in that service, or as stand-alone elements in your regular service.

3 CommentsJulie McDonnell Triples

Close watchers of the ringing ‘scene’ — or of Songs of Praise — will be aware that there is currently a significant fundraising exercise underway, raising millions of pounds to fight leukemia — by ringing bells.

The campaign was begun by Julie McDonnell, herself a survivor and sufferer from the disease, and also a ringer. She set up a campaign called Strike Back Against Blood Cancer and persuaded some generous sponsors to donate money to the campaign whenever a quarter peal of the new method (or methods) is rung. The new method is fittingly called “Julie McDonnell” and exists for various numbers of bells.

Last night at another tower’s practice the tower captain said she’d like to ring a quarter peal of Julie McDonnell Triples at some point, and pointed to a blue line of the method drawn on the tower whiteboard. After we had looked at it for a few minutes some of us had a go at ringing a plain course, which we did susccessfully at the first attempt.

It’s a fairly simple method, with “frontwork” done by the 4 and the 2, and “backwork” done by the other bells; and 3–4 dodges to transition between “frontwork” and “backwork”

Starting on the 4 do the “frontwork” dodge 1–2 down, lead, make 2nds; dodge 1–2 down lead, make seconds, becoming the 2. Having made 2nds and become the 2, it’s lead, dodge 1–2 up, make 2nds, lead, dodge 1–2 up and out, dodging 3–4 up and becoming the 3. Or to summarize the “frontwork” slightly differently: (dodge 3–4 down), dodge down, lead, 2nds, dodge down, lead, 2nds, lead, dodge up, 2nds, lead, dodge up; (and dodge 3–4 up).

The “backwork” starting from the 3 is: lie, make 3rds, lie, make 3rds, lie, make 5ths, lie make 3rds, lie, make 3rds, lie, dodge 3–4 down becoming the 4. Or, taking the lying and all the intervening plain hunting as implicit: 3rds, 3rds, 5ths, 3rds, 3rds.

The starts are:

2: in the middle of the frontwork

3: at the start of the backwork

4: at the start of the frontwork

5: has just made 5ths in the middle of the backwork; lie, 3rds, lie, become the 6

6: has nearly finished the backwork, so down to 3rds, lie, then dodge 3–4 down

7: has just done the first lot of 3rds; so lie one blow in 7ths, then 3rds, then 5ths

Bobs are the same as plain bob:

About to make 2nds: run out and become the 3 so begin the backwork

About to dodge 3–4 down: run in and become the 2, so lead and do the second half of the frontwork

About to dodge 3–4 up: make 4ths place and become the 4, so turn round and entirely repeat the frontwork.

Michael Perham

The Diocese of Gloucester has this morning announced that Michael Perham, Bishop of Gloucester between 2004 and 2014, died on the evening of Monday 17 April.

Michael Perham played a very significant role in the liturgical life of the Church of England, and was a member of the Liturgical Commission between 1986 and 2001. He was a contributor to the books that became Lent, Holy Week, Easter, The Promise of his Glory and Enriching the Christian Year, and then to Common Worship.

In the announcement, Bishop Michael’s successor as Bishop of Gloucester, Bishop Rachel Treweek writes:

0 CommentsIt is with great sadness that I am writing to inform you that Bishop Michael died peacefully at home on Monday evening, April 17, following a special Easter weekend with all the family.

I last saw Bishop Michael on Tuesday 11 April during Holy Week. Not only was it good to share together in the Eucharist on that occasion but also to preside at the Chrism Eucharist on Maundy Thursday knowing that the Dean would then be taking Bishop Michael bread and wine from our service in Gloucester Cathedral with the love and prayers of the Diocese.

singles in Stedman Doubles

On a good practice night we have enough ringers able to ring Stedman Doubles, and we are gradually getting better at it, and more people are able to cope with singles so that we can ring an extent of 120 changes, rather than just a plain course of 60.

Singles in Stedman Doubles seem to cause quite a bit of confusion. They also have a number of nicknames or mnemonics which aim to remind the ringer what to do. A common pair of nicknames is “cat’s ears” and “coathangers”, referring to the actions taken by the two bells affected by the call. I could never get used to these, especially “coathangers” and worked out my own way of dealing with singles.

The first thing to remember is that Stedman consists of three bells on the front which plain hunt for six blows, and then change direction, together with pairs of bells above third place which double dodge out to the back and then back down to the front again. In Stedman Doubles the only double dodging is in 4–5 up and 4–5 down. And the important thing to remember is that a single affects only the pair of bells double-dodging in 4–5 up and down. The three bells on the front are entirely unaffected by the call.

The effect of a single is to swap two bells over, and in Stedman Doubles it swaps over the two bells that are double-dodging 4–5 up and down. That’s really all you need to know. The ringer who started out thinking that they were going to double-dodge 4–5 up has to turn around swap places with the ringer who started out thinking they were going to double-dodge 4–5 down. And vice-versa.

Or to put that another way, if you are double-dodging 4–5 up and a single is called then you become the bell double-dodging 4–5 down. And if you are the bell double-dodging 4–5 down then you become the bell double-dodging 4–5 up. (Of course in both cases the double-dodges up and down are not really double-dodges because they are incomplete, but we can gloss over that complexity.)

What does this mean in practice? Let’s consider, first, the bell that would, if there were no single, double-dodge 4–5 up. The ringer will count their place something like this:

- fourth, fifth, fourth, fifth, fourth, fifth

and then they will lie at the back and double dodge 4–5 down.

Meanwhile the ringer who would be double-dodging 4–5 down with them will count their place something like this:

- fifth, fourth, fifth, fourth, fifth, fourth

and then go down to the front, either as a quick bell or a slow bell.

The effect of the single is to swap the two bells over at the fourth stroke (a handstroke) of these six changes, so that the bell that starts dodging up ends up dodging down:

- fourth, fifth, fourth, fourth, fifth, fourth

This bells is now dodging down, so it must next go down to the front.

Meanwhile the bell that starts dodging down ends up dodging up

- fifth, fourth, fifth, fifth, fourth, fifth

This bell is now dodging up, so it must lie in 5th place and double-dodge down before joining the front work, either as quick bell or as slow.

As for whether you go in quick or slow: if you are affected by one single (or by an odd number of singles) then you do the opposite of what you would otherwise have done. If you came out quick and would have gone in slow, then after a single you go in quick. Or if you came out slow and would have gone in quick, then instead you go in slow. (That’s because you have swapped places with the the other bell, and it becomes the bell that does what you would have done, and you become the bell that does what it would have done!)

For me, this is where blue lines explaining the single — helpful though blue lines generally are — here just complicate matters. In this instance I find it easier just to switch from ringing one place bell (4th’s place) to ringing another (5th’s). Or vice versa.

1 CommentCalling Bob Minor: a different composition

Thanks to Tim Rose’s website here is a composition for a quarter of Bob Minor that looks to be rather easier to call than the one I considered before. Tim does a pretty good job of describing the composition, but for the sake of completeness and to aid my own understanding I’ll put it all in my own words.

As in the previous composition, this quarter consists of a 720 followed by a 540, making 1260 changes in total.

First we look at a plain course of Bob Minor. The lead ends (when the treble leads at backstroke) look like this:

123456

135264 (3 make 2nd’s, 5 3–4 up, 2 3–4 down, 6 5–6 up, 4 5–6 down)

156342 (5 make 2nd’s, 6 3–4 up, 3 3–4 down, 4 5–6 up, 2 5–6 down)

164523 (6 make 2nd’s, 4 3–4 up, 5 3–4 down, 2 5–6 up, 3 5–6 down)

142635 (4 make 2nd’s, 2 3–4 up, 6 3–4 down, 3 5–6 up, 5 5–6 down)

123456 (2 make 2nd’s, 3 3–4 up, 4 3–4 down, 5 5–6 up, 6 5–6 down)

This gives us 60 changes in a plain course, but if we call a bob just before it comes back to rounds the last row becomes

142356 bob (4 runs in, 2 runs out, 3 makes the bob, 5 dodges 5–6 up, 6 5–6 down)

If we do this three times, then the lead ends at each of the bobs are:

123456

142356 bob

134256 bob

123456 bob

These bobs are each called when the tenor is in the ‘home’ position, i.e. dodging 5–6 down. Now we have a touch of three courses or 180 changes.

We can extend each of these courses (each ending with the bob at ‘home’) by inserting some extra calls that don’t affect the course end. We can do this by adding in a different fairly simple touch of four calls, that turns each 60 into a 240. Each call is made when the tenor is dodging 5–6 up, i.e. at ‘wrong’. The four calls are bob, single, bob, single. The tenor, dodging in 5–6 up at each call, is unaffected by any of them, and after these four calls the touch comes back to rounds.

We can write out the lead ends starting from rounds thus:

123456

123564 bob ‘wrong’; 5 makes the bob

136245 plain: tenor dodges 3–4 up

164352 plain: tenor makes 2nd’s

145623 plain: tenor dodges 3–4 down

152436 plain: tenor dodges 5–6 down ‘home’

125364 single ‘wrong’; 5 makes the single

156243

164532

143625

132456

132564 bob ‘wrong’; 5 makes the bob

126345

164253

145632

153426

135264 single ‘wrong’; 5 makes the single

156342

164523

142635

123456

After 240 changes this comes back to rounds, but if a bob is called just before that, then it changes the last row to

142356 bob ‘home’; 5 and 6 unaffected

This is just what the simple touch (3 ‘home’s) did, and similarly, ringing this three times will then come back into rounds at 3 × 240 changes, i.e. after 720 changes so we have rung the first 720 of the quarter peal, an extent on 6 bells, or every possible combination.

The lead ends after each 240 are:

123456

142356 bob ‘home’

134256 bob ‘home’

123456 bob ‘home’ rounds

These are exactly the same course ends as we got with the simple “three homes” 180 touch.

We can continue to ring this pattern a further two times and then we shall have rung another 480 changes, each ending like this:

142356 bob ‘home’

134256 bob ‘home’

That makes 720 + 480 changes, or 1200. We need another 60 changes to reach 1260 for the quarter peal, and we need to get back to rounds. And that’s exactly what our simple “three homes” touch does – its last course of 60 changes turns 134256 into 123456 with just one bob at the very end. See the lead ends for that simple touch at the start of this article. So we ring the last 60 of that 180, omitting the bob-single-bob-single at ‘wrong’ that we used to extend the 60 into a 240.

The quarter peal becomes:

bob ‘wrong’, single ‘wrong’, bob ‘wrong’, single ‘wrong’, bob ‘home’ – repeat 5 times in total

bob ‘home’.

Or to spell it out in more detail:

bob, plain, plain, plain, plain;

single, plain, plain, plain, plain;

bob, plain, plain, plain, plain;

single, plain, plain, plain, bob;

— repeat all the above 5 times in total, then finish with

plain, plain, plain, plain, bob.

Several other features make this easy for the learning band:

- The tenor rings plain courses throughout, unaffected by the calls which always occur when it is in 5–6 up or 5–6 down.

- The 5 makes 3rd’s at every single; no other bell needs to worry about making the single; this is very helpful if not all the band are fully confident about singles

- The 5 also makes 4th’s at every bob at ‘wrong’, and dodges 5–6 up with the tenor at every bob at ‘home’

- Otherwise the calls permute the 2, 3, and 4. In each 240 one of them will be unaffected, dodging 5–6 down with the tenor at every call: in the first 240 this is the 4, in the second the 3 and in the third the 2. The fourth is the same as the first, so the 4 is unaffected, and the fifth is the same as the second, so the 3 is.

- When there is a bob at ‘home’ at the end of each 240, it comes one lead earlier than a bob or single would otherwise have been called

- And then the bob at ‘wrong’ is the very next lead.

Update

Steve Coleman discusses this QP composition (and the earlier one) in his Bob Caller’s Companion (which along with his other ringing books is available here). He suggests the other one is the simpler. He also makes a couple of interesting observations. First is to call the 540 before rather than after the 720, and to call the 60 at the start of the 540 rather than at the end. The advantage of this is that the 60 is a complete plain course, starting from rounds and just as it’s about to come back to rounds there’s a bob, and then the sequence of five 240s begins. So the variation in the composition is at the start – and if anything goes wrong you can start again, with a only a few minutes wasted. If this is done, then after that first bob it’s the 3 that is unaffected in the first 240, then the 2, then 4, 3, and 2 respectively. The composition comes back to rounds with the bob at ‘home’ at the very end of the fifth 240.

Coleman also notes that this block of W‑SW-W-SW‑H can be used for a QP of Bob Major. Instead of there being 240 changes in each part (12 changes in each lead, 4×5=20 leads in each part), in Major there are 448 (16 changes per lead, 4×7=28 leads per part), and so ringing it three times is 1344 changes, at which point it comes back to rounds without anything else needed and that will suffice for a QP. In Major, 6, 7 and 8 are all unaffected by all the bobs and singles, ringing plain courses throughout. The 5 front bells do all the same work as they do in Minor, with the addition of hunting to 8th place and back, and dodging 7–8 down and up.

0 CommentsCalling Bob Minor, further thoughts

Another aspect of calling a long touch – let alone a quarter peal – is remembering where you’ve got to, and what happens next.

The only long touches I’ve previously called have been quarter peals of bob doubles, where the problem is keeping track of calling exactly 10 120s, and not losing track of how many you have rung so far. For that method I’ve adopted the technique of associating each successive 120 with a particular bell, so that you call a 120 associated with the 2, then a 120 associated with the 3, then the 4, then the 5; then another 120 associated with the 2, then the 3, 4 and 5 in turn; and then yet another 120 associated with the 2, then the 3 – and then you’ve rung 10 120s.

The advantage of this aide memoire is that while ringing you just have to remember which bell is associated with that 120, and at the end of the 120 you move on to the next bell. And you have to remember whether this is the first sweep, the second, or the last (half-)sweep, but that is very considerably easier to do, partly because counting to 2 is an awful lot easier than counting to 10, and also because a look at the clock will give you a pretty clear indication of which sweep you’re in. Two further points about Bob Doubles. First, it is very easy to associate a particular bell with each 120, because in any 120 a particular bell will be the observation bell, unaffected by the calls, and the conductor is focussing on that bell and calling bobs when it is about to ring 4 blows in 5th place. So it is easy and natural to associate a bell with a 120 and to remember which bell it is at any moment. The second point is a footnote to anyone reading this who might be setting out to ring a quarter of Bob Doubles: don’t forget that 10 120s is only 1200 changes and you need to add another 60 to get to the quarter peal.

So how is this applicable to quarters of Bob Minor, and particularly to the composition discussed? One idea is to use a similar counting scheme to keep track of the courses of the composition. In a 1260 of Bob Minor there are 105 leads of 12 blows each, or 21 courses of 60 blows each. Each course is 5 leads in length and at the end of each the tenor – which is entirely unaffected by all the calls of Bob and Single – returns to its ‘home’ position of dodging 5–6 down. Unfortunately, and unlike the Bob Doubles counting scheme, there is no obvious and easy natural association of a course with a different bell.

What we have instead is a 720 of 12 courses followed by a 540 of 9 courses. If we allocate all 6 bells to a course then that is twice through the bells for the 720, and one and a half sweeps through for the 540:

1: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

2: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, plain

3: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

4: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, plain

5: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

6: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, single (home)

1: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

2: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, plain

3: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

4: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, plain

5: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

6: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, single (home) which completes the 720

1: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

2: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, single (home)

3: plain, plain, plain, plain, single (home)

4: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

5: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, single (home)

6: plain, plain, plain, plain, single (home)

1: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, bob (home)

2: bob (wrong), plain, plain, plain, single (home)

3: plain, plain, plain, plain, single (home) which completes the 540

Does this help at all? I’m going to think about that!

0 Comments