Nicaea and the date of Easter

This article was first published in the June 2025 issue of Transforming Worship News (formerly Praxis News of Worship).

The date of Easter is often regarded as rather complicated, too complicated for nearly everyone to worry about. But it links us with the origin of the annual festival, and the way the early Church celebrated the resurrection.

When the Emperor Constantine decided that Christianity was the best hope of unifying his empire, he found disagreement on several topics, including the nature of Christ and the date on which to hold an annual celebration of his resurrection. The Council of Nicaea in 325 attempted to resolve both issues, agreeing a statement of belief and formalizing the date of Easter.

The story begins with the Jewish festival of Passover, held at the first full moon of the spring, when the moon lights the sky all night. In the Jewish lunar calendar this day is 15 Nisan, and the previous day, 14 Nisan, is the day of preparation. In the late afternoon of that day, until the Temple was destroyed, Passover lambs were slaughtered in the Temple precincts. They were then roasted and eaten at the Passover meal that began with the full moon at sunset, the start of 15 Nisan. In the fourth gospel, the crucifixion was on 14 Nisan, and in the synoptics on 15 Nisan.

There is no explicit evidence in the New Testament of a yearly Easter. The focus in the early Church was the weekly celebration of the resurrection on the first day of the week, every Sunday. Although it is not entirely clear – and there may have been a cover up – it seems that Christians in Jerusalem and the Jewish diaspora did keep an annual festival, but Gentile Christians probably didn’t. The former group kept an annual celebration of both the crucifixion and resurrection on 14 Nisan, whichever day of the week that fell on.

Perhaps influenced by this annual feast kept in the diaspora, other Christians began to observe it and a fast on the previous day. But rather than keeping it on 14 Nisan they celebrated the following Sunday, the day of the weekly commemoration of the resurrection. Perhaps just as today, it was more convenient to transfer weekday festivals to Sunday.

These two groups co-existed until at the end of the second century, Pope Victor I controversially excommunicated those who kept 14 Nisan – the Quartodecimans (or “fourteeners”). A century later the dispute had not ended although the Quartodecimans were a distinct minority. So when, commanded by Constantine to agree a common date, the bishops assembled at Nicaea it was not surprising that majority opinion, favoured by Rome and other major sees, prevailed. The Council ruled that the annual paschal feast, celebrating the resurrection, should be observed on the Sunday after the first full moon of the spring, the full moon after the equinox.

The Council did not prescribe how this might be determined in advance, and initially it was perhaps left to direct observation. Competing tables of dates soon emerged, frequently based on a 19-year lunar cycle that had been known since at least the Babylonians. The date of the equinox, which in the first century had fallen on 25 March, had by the fourth century drifted to 21 March. Tables from Alexandria were generally regarded as the best, and the declaration each year from that see of the date of Easter was usually followed, though for many years the see of Rome used different tables so occasionally Easter would fall on another date. Eventually the tables compiled and extended by the sixth-century monk Dionysius Exiguus were accepted as definitive. These continued in use throughout the Church, across the schism between East and West. As the middle ages wore on it was recognised that both lunar and solar components of the tables were increasingly inaccurate, but it was not until after the Reformation that Pope Gregory XIII unilaterally introduced a modified calendar with self-correcting lunar tables. Although these were gradually accepted by the churches of the Reformation they have not been adopted in the East, at least not for determining Easter.

In the twentieth century there were some moves to fix the date of Easter, but at the end of the century the World Council of Churches proposed abolishing calculated tables based on the approximate 19-year cycle and instead using accurate astronomical calculations of the equinox and the full moon as observed in the time zone of Jerusalem. They suggested this might be adopted in 2000 when both Eastern and Western calculations coincided on the same date. There was some support for this from Rome, from Anglicans and various churches of the Reformation and some Orthodox churches, but it was far from universal. In this 1700th anniversary year of Nicaea, when Easter dates again coincide, the WCC has re-iterated its proposal. Once again, it seems unlikely to gain enough support to be brought in.

Simon Kershaw remembers trying to calculate Easter from the tables in the BCP while enduring long sermons as a young chorister at Evensong. He has continued to calculate and write about the date of Easter.

2 CommentsThe Coronation of English and British Kings and Queens

(Coronation of King George VI, 1937, painted by Frank Salisbury; Royal Collection Trust)

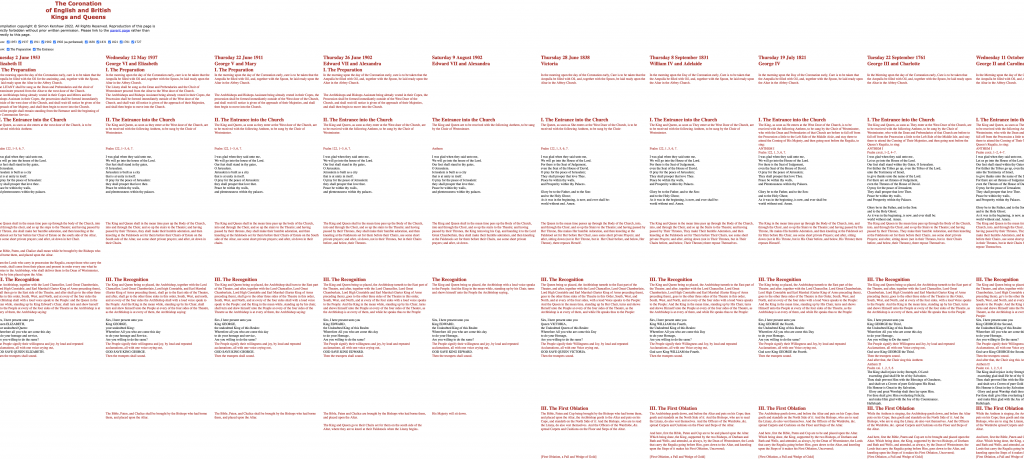

Beginning with the coronation of James I in 1603 there have been sixteen English-language coronations of English, or from 1714 British, monarchs. Before that, upto and including the coronation of Elizabeth I, the service had been conducted in Latin. The seventeenth, for King Charles III, is scheduled to take place on Saturday 6 May 2023.

As a small boy, over half a century ago, I was captivated by a souvenir of the 1937 coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth which belonged to my grandparents, and which contained the text of the service along with copious illustrations and some historical notes. From 1994 I have collected copies of the order of service of every coronation back to that of George IV in 1821, along with reproductions and editions of the earlier services back to 1603, as well as the music editions that have been published since 1902.

For some time I have thought of producing an historical edition of the coronation service with the different texts in parallel columns, making it easy to see the changes that have been made over the centuries. This is a bit complex to produce as a book (and perhaps not commercially viable) but a web page is easier to create, and can have other helpful features such as hiding or showing different sections of the page. So now there is a new page at oremus.org/coronation that contains the text of all the coronation services from 1953 back (currently) to that of George II in 1727. Work on adding earlier texts continues.

In each column the texts are aligned so that corresponding rubrics and spoken words match across the page. Individual columns can be hidden, making it easy to compare different years. Hiding rows, or sections of the text across all columns, is a feature that will be added soon.

The coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra scheduled for June 1902 was postponed because of the king’s illness. When it did take place in August, a number of modifications were made to place less stress on the convalescent king. Both the June and August texts are included in parallel columns.

With the Coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla scheduled for next year, I hope this will be a useful historical archive.

0 CommentsLiturgy for the reburial of a king

The remains identified as those of King Richard III were re-interred yesterday in Leicester Cathedral in a service broadcast live on Channel 4.

The order of service for the re-interment is available as a pdf file on this page, or (direct link to pdf) or here.

0 CommentsAlternative Services

This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of the enactment of the Prayer Book (Alternative and Other Services) Measure 1965.

It was this Measure of the old Church of England Assembly which for the first time enabled the Church to revise the 1662 services of the Prayer Book and to make extra provision. Until that point only the 1662 Book (with minor amendments passed by Parliament in the 19th century) had been legal, and the Church’s great attempt after the First World War to revise the Book had twice been lost in Parliament after passing the Church Assembly. The Church’s response to that failure was a resolve to never again subject liturgical texts to Parliamentary revision. But it took nearly 40 years (with an intervening World War) before this Measure was approved by the Assembly (Bishops: 30 in favour, 0 against; Clergy: 200 to 1; Laity: 203 to 11) and then by each House of Parliament. The Measure did not contain any liturgical text, but provided a mechanism whereby texts which were alternative to or additional to Prayer Book texts could be approved by the Church Assembly for use for a few years.

The first fruits of the Measure were the authorization of large parts of the proposed 1928 Book, and these became known as the Alternative Services First Series. Almost simultaneously a Second Series began to be published and authorized. These represented the work of the new Liturgical Commission, and in many cases they departed from the structure of the Prayer Book services, introducing the fruits of liturgical scholarship and ecumenical thinking, but still using language that was lightly traditional. The First Series marriage and burial services continue to be authorized, and much of the Second Series Holy Communion service continues as Common Worship Order One in Traditional Language.

The Measure provided for temporary experimentation over a small number of years, and it was an essential step on the route to the modern language services of Series 3, brought together only 15 years after the Measure in the Alternative Services Book 1980. By that time the Measure had been replaced, repealed entirely by the Worship and Doctrine Measure 1974. That Measure enabled the Church to make provision by canon law for the authorization of ‘forms of service’, and is the current legal basis for all liturgical texts including the 1662 BCP as well as Common Worship.

0 CommentsParish Communion

It’s hard to imagine what the Church of England was like before the Parish Communion movement — and yet the movement itself is virtually unknown today. Through the majority of the twentieth century, certainly right up until the 1960s, the movement was active in promoting its vision of life and worship in the Church of England, attracting support from bishops and synods. But it very quickly faded from the scene, so that even those of us who grew up in the 1960s Church may well not have come across it.

At the same time as the Liturgical Movement was growing across the Roman Catholic Church, recovering a sense of the corporate nature of the liturgy, the Parish Communion movement (as it came to be called) was born and grew in England. The two movements seem to have begun and developed independently, though eventually they came into contact.

The history of the Parish Communion movement is told in Donald Gray’s book Earth and Altar: Evolution of the Parish Communion in the Church of England to 1945 (Alcuin Club Collections 68, 1986). Its roots lie in the Anglo-Catholic revival and the Oxford Movement, beginning with John Keble’s Assize Sermon in Oxford in 1833. The resulting interest in sacramental worship led to an increase in the celebration of Holy Communion, frequently with an increasing use of ceremonial. Because of the requirement of many Anglo-Catholics that the sacrament should be received fasting, it became the custom for the main ceremonial celebration of the Eucharist in many such parishes to be almost entirely a non-communicating act. Only the priest and perhaps one or two others would receive Communion. For the rest of the congregation, attending after Sunday breakfast just as they had previously attended Mattins, this was a choral, ceremonial and devotional high-point, but one in which they were passive rather than active participants. For the more ‘devout’ there would typically be one or more early celebrations at 8am and perhaps 7am so that they could receive the sacrament before breaking their fast.

At the same time, Anglo-Catholic priests were noted for their work in impoverished and neglected areas, particularly in the slums and docklands of large English cities and ports, and various groupings of Christian socialists and other activists came and went.

The Parish Communion movement combined two main aims:

- it strove to make the celebration of the Eucharist the primary service on a Sunday morning in each parish church, and to insist that it was a service at which the congregation should receive the sacrament;

- and it emphasised the link between that celebration of the Eucharist and social action

Social action was considered to be very closely aligned with the Labour movement, which itself was growing in strength during the first half of the twentieth century. At a time when the Church of England was still very widely regarded as the Conservative Party at prayer, the Parish Communion movement might be regarded as the Labour Party at prayer.

In order for the congregation to receive the sacrament before breakfasting the time of the service had to be one that was earlier than the norm of Mattins or High Mass at 11am, but late enough for them to have a bit of a lie-in on their weekly day of rest. 9am or 9.30am became a popular time. Parishes which still have their main Sunday morning Eucharist at this time were quite likely ones that participated in the Parish Communion movement. Frequently the service was followed by a parish breakfast. Not all those associated with the movement were insistent on fasting before communion — but its leaders and advocates were adamant on this point.

And what about ‘social action’? This other important part of the life of the Church was focussed on a weekly ‘parish meeting’, perhaps in the middle of the week, at which such issues could be discussed and support given to various initiatives, whether local, national or international.

What the promoters of the Parish Communion emphasised was the corporate nature of the Church, the corporate nature of the Eucharist, and the essential and corporate nature of the social action that was intimately bound up with them. The great manifesto of the movement was a collection of essays, The Parish Communion, published in 1937, edited by the Revd Gabriel Hebert. Momentum grew, and after the Second World War Parish and People was established as a group to campaign for the goals of the movement. With the reality of a majority Labour government from 1945, perhaps the political angle of the movement changed. By 1962, when Parish and People was celebrating the 25th anniversary of the publication of The Parish Communion, the Christian Socialist Movement (CSM, recently renamed Christians on the Left) was being set up. There was much overlap between the two groups, and the CSM followed on from a plethora of similar socialist groupings, but gradually the two movements separated. By the end of the 1960s, having to a large extent achieved its liturgical aims, Parish and People had faded, although it continued to exist until the end of 2013.

What then did the Parish Communion movement achieve, and what can be learnt from it? Primarily it reminded large chunks of the Church of England (and other Anglican churches too) of the centrality of the Eucharist, and of the importance of a corporate celebration at which all received the sacrament. It was successful in promoting this ideal not only across much of the Anglo-Catholic world in which it originated and across the more central groups in the Church, but also into the more central-evangelical parts of the Church, so that a parish communion on a Sunday morning came to be seen as the norm. It linked this fundamentally with what it saw as the social justice agenda of the Church’s mission — though as socialism was tried in the secular world this perhaps became a party-political position that did not always sit well with those who were hearing the liturgical message. It fell short, perhaps, in a lack of attention to evangelism.

These three strands — the liturgy, action for social justice, and concern for evangelism — are the areas that we shall explore in this blog. The social justice agenda itself will largely be left to our sister Thinking Anglicans blog: here our concern is how that is linked to the liturgy. Similarly the topic of evangelism itself will be explored in the context of the liturgy: of what we do in Church, how our buildings serve us as local centres of worship, justice and evangelism.

4 CommentsLiturgical Basics

There is a whole list of topics that I hope to introduce into ‘Thinking Liturgy’. Before doing that I want to sketch out a little liturgical history and a little liturgical interpretation. It will only be a sketch because some of it will be the basis of some of those future articles, so the detail will be postponed until those articles are written. But it’s only fair that readers should see a little of one of the key premises.

Let’s start with a little — only a little — history.

For many readers, I expect that liturgical history is neatly encapsulated by Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy. This pivotal book, first published in 1945, outlines Dix’s thesis that the fundamental form of the Eucharist was a ‘Four Action’ shape of Offertory, Consecration, Fraction, Communion — or if you prefer, Taking, Blessing, Breaking, and Sharing. Dix suggested that all the various forms of the Eucharist could be traced back to this original pattern universally used in the earliest Church, itself deriving directly from an initial seven actions found in the New Testament accounts. This concept of a Four-Action shape was very influential in post-War liturgical revision and it can be seen in the work of the Liturgical Commission of the Church of England from the publication of Series 2 in 1966, through Series 3 in 1973 to the Alternative Service Book 1980 and on to Common Worship in 2000. In these two later books the concept is modified somewhat, so that two of the four actions are regarded as more significant and two as less so: ‘taking’ is preparatory to ‘blessing’ and ‘breaking’ to ‘sharing’.

More recent liturgical scholarship has questioned Dix’s premise (as did some at the time). There is really no evidence that there was a single original eucharistic structure, let alone that it follows Dix’s Four-Action shape. In particular, Paul Bradshaw, in his book Eucharistic Origins lays out what we have as the earliest evidence of the Eucharist. There are essentially three points to make, and the first two effectively demolish Dix’s shape. First, that actually there is very little evidence; and secondly that the evidence we do have is diverse — in the earliest surviving records different groups do different things. Eventually some of these patterns and practices merge or disappear under various influences. But as far back as we can go, practice is even more varied than it later became, and there is no reason to think that a single model underlies this.

For our purposes, I want to draw out a third point. This is what I like to call the ‘Monty Python got it wrong’ comment. Monty Python is not necessarily renowned for theological accuracy, but in one of their comedy sketches the Pope summons Michelangelo and castigates him for his painting of the Last Supper which contains several major inaccuracies; Michelangelo, rather than repaint the picture, suggests that it be retitled the Penultimate Supper on the grounds that there must have been one, and there is no record of what happened at it; the Pope retorts (in a line that has stuck with me for 35 years) ‘the Last Supper is a significant event in the life of our Lord; the Penultimate Supper was not’. Clearly, as John Cleese’s Pope says, the Last Supper was a significant event. And it clearly has an impact, a major impact, on our eucharistic thinking. But my contention is that it isn’t true to say that earlier suppers, earlier meals, were not significant.

These meals, and the scriptural record of some of them, are the background to the early Christian Eucharist. In Jesus’s earthly ministry, he ate and drank with his disciples and others; or to put it another way, when his disciples and others ate and drank Jesus was present with them. And after his death, his followers continued to experience his presence; most especially they experienced his presence when they broke bread together.

In this blog, I want to explore what this means for us today. How does this affect what we think we are about when we celebrate the Eucharist, and how does it affect the way that we go about celebrating the Eucharist? What does it mean for our words and actions, for our hospitality, for our teaching and mission? What does it mean for our architecture and church ordering even?

Other points of view are of course possible, and we shall explore some of those too.