Advent 4: 24 December 2023

Readings: 2 Samuel 7.1–11, 16; Canticle: Magnificat (Luke 1.46–55); Romans 16.25–27; Luke 1.26–38

“The angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth.”

In the name of …

Prequels.

Do you enjoy prequels?

Did you watch Endeavour as a prequel to Morse?

Or perhaps The Phantom Menace and others as prequels to Star Wars?

And what about books?

As a teenager

I worked my way avidly through CS Forester’s Hornblower novels,

reading them in story order,

and finding that all the earlier books were written after the later ones.

The conclusion of the story was already pre-determined –

Hornblower’s failure to achieve this or that;

the death of … spoilers.

Much of this was fixed by throw-away lines in the later books that were already in print.

And today’s gospel reading is a sort of prequel as well.

What’s it a prequel to?

Well, we heard a couple of weeks ago

the start of the gospel according to Mark.

(Mark the evangelist, that is, not Mark the vicar.)

Mark’s account is very widely regarded as the first gospel to have been written,

and so there was a time,

a short time perhaps,

when it was the only gospel in existence.

Perhaps you can remember from two weeks ago how it starts:

The beginning of the gospel [or: good news] of Jesus Christ, the Son of God[1]

and then it describes that beginning:

the preaching of John the Baptist,

and how Jesus arrives on the banks of the Jordan and is baptized by John.

So,

what was Jesus doing before the start of Mark’s account?

I think that’s a natural question to ask.

And in the culture of that time

it might not have been obvious

that he had been born,

or that he had grown from a baby to an adult man.

That’s a somewhat bizarre thing to say, isn’t it? What do I mean?

Well,

ancient mythology is full of stories that skip all that stuff.

Just one example

from the Roman poet Ovid,

who lived just a year or two ahead of Jesus and Luke.

His long verse collection Metamorphoses includes such a tale –

how the immortal gods

Jupiter and Mercury

decided one day to pay a visit in disguise to the mortal world.

They are spurned by everyone

until they meet an impoverished elderly couple,

Philemon and Baucis,

who invite them in and cook them supper

from their own meagre resources,

and gradually realize,

when the goblets of wine never empty,

that their guests are divine.[2]

Now if you think this is far-fetched,

then have a look at the Acts of the Apostles, at chapter 14,

where in an echo of Ovid’s tale, Luke tells us that

Paul and Barnabas are themselves mistaken for exactly the same two gods.[3]

So you can see perhaps

how the sudden appearance of Jesus in the earliest gospel account

as an adult acclaimed as God,

might also be open to misinterpretation.

That Jesus wasn’t really human,

but was a god in disguise.

Perhaps Luke was aware of speculation

about the origin of Jesus and his early life,

but whatever the reason,

he gives us two whole chapters about Jesus

before getting to John baptizing in the River Jordan

(where Mark had begun, remember?).

And here we are:

in the story it’s nine months before the birth of Jesus,

and Luke introduces us to Mary.

We don’t learn much about her though:

that she lives in Nazareth,

and is engaged to be married;

and via the angel that she is favoured by God,

and is related to Elizabeth,

who is herself expecting a child –

that’s the boy who in adulthood will become John the Baptist.

That’s pretty much all the story says about her.

And that’s because the story isn’t really about Mary.

It’s about Jesus.

The things that Mary says and does point us to Jesus.

The angel tells Mary she will have a son,

and that the Holy Spirit will overshadow her,

so that the child will be holy

and called “Son of God”.

Mary, then, will be the bearer of God the Son,

and we can see our Old Testament reading as a parallel to this.

King David wants to build a permanent home for the ark of the Covenant,

the holiest possession of the ancient Israelite people,

and regarded by them as the place where God dwelled.

But the prophet Nathan tells David

that it is not for him to build such a place,

that will come later;

but God will instead establish David’s line for ever.

Two prophecies for the price of one!

First, because Luke traces Jesus’s own ancestry back to King David –

seeing Jesus as fulfilling Nathan’s statement

that David’s line will reign for ever.

And secondly because

we have just heard how Mary will be the bearer of God –

it is her womb that will house God: God the Son.

So what does Mary do?

In the verses immediately after our gospel reading

she legs it,

and seeks out her relative Elizabeth.

And it is while she is with Elizabeth

that, Luke tells us, she praises God.

And earlier in our service today,

we sang a version of the words Luke records:

“With Mary let my soul rejoice”.

(You might like to have the words in front of you now.)

This song, the Magnificat, is not just a song of praise.

It’s also

a trailer or teaser for the story of Jesus,

for the story of Jesus’s mission and teaching,

the story of Jesus’s proclamation of God’s kingdom,

God’s rule.

Because in the Magnificat we can see parallels with Jesus’s later teaching:

- In the synagogue at Nazareth, for example, Jesus identifies himself:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me;

he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor,

release to the captives,

recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free.”[4] - And in another place he teaches:

“Blessed are you who are poor, [or] hungry, [or] who weep.

But woe to you who are rich, you who are full,

for you will be hungry.”[5]

These are the themes we have seen and sung in Mary’s Song,

and they are the themes that continue throughout Jesus’s ministry:

lifting up the hungry and poor,

exalting the humble and meek –

sending the rich away empty.

And in today’s gospel reading

we see them announced at the very start,

at the very moment that Jesus’s conception is first revealed.

Even as Jesus is conceived

Luke tells us that this message is proclaimed.

So is Luke’s account a good prequel?

Well, it’s the prequel that

to much of society

is almost the only bit of the story they remember.

In that sense, yes, it’s a really good prequel.

And yet …

The world around us

is drawing to the end

of its annual orgy of extravagant spending and extravagant consumption,

whilst all about we see:

poverty,

misery,

hatred,

war.

And though we shouldn’t begrudge people a bit of light and fun

and – above all – hope

in the midst of such difficulty,

nonetheless

our job,

our mission,

yours and mine,

is to make sure

that the rest of Jesus’s story is remembered too –

the proclamation of the good news that is the Kingdom of God,

where the poor and the hungry,

the homeless and the refugee,

the war-ravaged –

all who suffer, the downtrodden of society –

are raised up and satisfied,

and enemies are reconciled to each other.

And – our response should be to make that happen,

now, at Christmas time, yes – and also all year round.

Because all that is foreshadowed

in the news that we like Mary, heard today.

The good news

that the baby whose birth we are about to celebrate

saves us

and teaches us how to move

from lives governed by the prince of this world

to lives governed by the prince of peace.

Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.

[1] Mk 1.1 (NRSVAE)

[2] Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book VIII

[3] Acts 14.11, 12

[4] Lk 4.18,19 (NRSVAE)

[5] Lk 6.20–25 (NRSVAE), abbreviated

0 CommentsThe Transfiguration: 6 August 2023

Readings: Daniel 7.9,10,13,14; Psalm 97; 2 Peter 1.16–19; Luke 9.28–36

I don’t know about you, but I’m not much of a film-buff and I don’t often go to the cinema,

perhaps only once, maybe twice, a year, if that.

But I went to the cinema last weekend.

So, there are two big films on right now,

one that I’ll just gloss over as mostly pink

and another that I can say is somewhat grey.

Now I expect my three-year old granddaughter

would love to watch the pink one,

but it was the somewhat-grey film that Karen and I went to see.

It’s a story – a true story – set during the Second World War,

with a bunch of scientists racing to work out how to build a new weapon.

And not just any new weapon, but a new kind of weapon,

a weapon that will unleash untold power.

And just as they’re about to explode the very first test at Los Alamos

– a moment of high drama –

the hero, Robert Oppenheimer, remembers an earlier conversation

(in the film it’s) with a chap called Albert Einstein,

a conversation about an important question –

what’s the worst that might happen in the test?

Well, comes the reply, it could set off a chain reaction,

a chain reaction that might ignite the whole atmosphere,

a chain reaction that might consume and destroy all the earth.

They don’t think that’s very likely, but it is possible.

(And I think you’ll agree that is rather a big downside to any decision.)

So of course they proceed with the test.

There’s a small starting explosion,

and then a great shining, blinding, white light

and then a massive fireball

as the chain reaction in a small lump of uranium causes an explosion of unparalleled ferocity

and then

a great booming sound, the shockwave of the explosion.

The test is a success. Oh, and the earth isn’t destroyed either.

And so – a few weeks later – on the 6th of August, 1945,

their new bomb is dropped on the Japanese city of Hiro-shima.

And just a few days later another atomic bomb is dropped on Nagasaki.

As many as 200,000 people –

men, women, children,

mostly civilians –

were killed,

and many more suffered lifelong injury from radiation sickness.

Japan surrendered, bringing the Second World War to an end.

Light and sound – signifying death and destruction and conflict on an unprecedented scale.

It’s a true story, and today, today is the 6th of August,

today is the 78th anniversary of that first atomic bomb at Hiro-shima.

It’s a day when the world remembers those killed,

those injured,

[[those whose lives were affected,

the destruction wrought ]]

by those two life-destroying atomic bombs.

And

when we all hope and pray that it won’t happen again.

But the 6th of August is also a day that the Church has celebrated as a holy day

for hundreds and hundreds of years.

We heard the story in our gospel reading from Luke this morning.

Jesus and some of his disciples climb up a hill,

and there the disciples see Jesus transfigured –

shining white with brilliant dazzling light,

and they hear a great booming voice.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

Now, I’m not going to try and explain what happened,

or try to second-guess what the disciples “really” saw and heard.

But the effects of this light and this sound

are very different from the destruction caused by the light and sound at Hiro-shima.

This light and this sound have a meaning totally different from that of the atomic bomb.

And as a result, the disciples understand that Jesus’s message comes from God.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

Rather than death and destruction and conflict,

this bright light signifies

life and healing and peace.

That’s the life-giving message that Jesus brings,

the life-giving message that Jesus brings from God.

That God wants us to have life in all its fulness,

to live in love, and to care for one another

in the good times, yes –

and, even more so, when the going gets tough.

God wants us

– as Jesus says elsewhere in the gospels –

to feed the hungry,

to shelter the homeless and the refugee,

to care for the sick and the needy,

to lift up the oppressed,

to forgive and be reconciled with those who have wronged us.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

It’s the message that God, in Jesus,

saves us from the chain reaction

of hate and wrong-doing and death,

the chain reaction that leads to ever more hate and wrong-doing and death.

God in Jesus offers us an alternative,

an alternative chain reaction of hope and caring and forgiveness.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

It’s not an easy way out, though.

Caring and reconciliation can be costly too,

as we see up there, above me,

with Jesus put to death on the Cross.

Because not everyone appreciates caring,

not everyone appreciates it when people stand up for others,

not everyone appreciates it when people look for reconciliation.

But Jesus’s message is that this way is God’s way.

And in the Transfiguration, in Luke’s story that we heard earlier,

[[and also Peter in his letter that we heard too,]]

the disciples realize that Jesus’s message is God’s message.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

And they do their best,

after Jesus’s death and resurrection,

to pass his story on to their successors,

and – and here’s the important bit –

not just to tell the story,

but to live as the community of people

who try to do those things.

And it’s into this community that we have come today

to see C_ baptized.

This is the community of people – here in this church in St Ives –

who are the followers of Jesus,

the successors,

(many hundreds of years later, with others here and around the world)

the successors of Jesus’s own disciples –

a life-giving, life-enhancing chain reaction.

Now, of course, we’re human, and we get things wrong.

We aren’t perfect

and we don’t always agree

and we don’t always look after one another as we should.

But we are that community,

that is what the Church is,

that is what the Church tries to be;

and we are committed to journeying together

and trying to understand and to live as that community,

the community of Jesus’s followers.

And so – today – we welcome C_ into this community.

Now, it’s a two-way thing, C_.

For your part,

you will affirm the importance to you of Jesus and his message,

and the importance in your life of the divine, of God,

and the importance in your life of this community of faith and prayer and worship.

And we, the members of that community,

we will affirm our support for you as you make this step.

We will journey together:

we will learn from you

as you learn from us.

We will do things together

to share the good news that Jesus shared with his disciples,

and to care for those among us and around us who are in need.

And we will do it all with God’s help.

We’ll have fun together

and sad times together.

If we are honest, we know that sometimes we might even get cross with each other.

But we know that that’s because we each care,

and that, in Jesus, through Jesus,

there is always forgiveness and reconciliation.

And if that sounds a bit like a family,

well, that’s because the Christian community, the Christian Church,

is like a family.

It doesn’t replace the family that we live with.

But it is a new family, God’s family,

that we each become part of at our baptism.

And it is into God’s family, C_, God’s life-enhancing family,

that we are now going to welcome you.

Amen.

0 CommentsCoronation Liturgy Talk

(The Coronation of Queen Victoria, 1838, painted by Sir George Hayter; Royal Collection Trust)

Last week I participated in a “colloquium” organized by Praxis on the subject of the Coronation, giving an introductory talk on the elements of the service or liturgy at previous coronations. (We don’t yet have details of the 2023 service.) The other major presenter was the Very Revd Dr David Hoyle, the Dean of Westminster, who is closely involved in the planning and will be a major participant at the service.

The slides I used at that talk can be found here, in two versions – a large illustrated version and a small version with no illustrations.

- illustrated PowerPoint (126MB); PDF (1.2MB); PDF with notes (588kB)

- text only PowerPoint (100kB)

Both versions contain some notes, and they can also be read in conjunction with my earlier post on the Coronation liturgy.

Additionally a recording of the colloquium is available on YouTube. My section starts at about 7 minutes in – do watch all the recording if you have time.

0 Comments

The Coronation Oil

The oil that will be used to anoint the king and queen at their coronation on 6 May has been consecrated in Jerusalem by the Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and the Anglican Archbishop. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s website reports the details here, and that article is archived below.

0 CommentsThe Coronation Liturgy

This is a longer version of an article published in Praxis News of Worship, March 2023.

In 973 at Bath Abbey, Edgar was crowned King of England by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Coronation service in use derives directly from that compiled by Dunstan over a thousand years ago. It has gone through several revisions or “recensions”, with the third being used through the later Middle Ages and (in translation) for the first four Stuarts. The last major revision was made in 1689 by William Compton, Bishop of London, for William III and Mary II, but it has been tweaked for each subsequent occasion, with new monarchs usually wanting a shorter ceremony than their predecessor’s, and new anthems or settings being commissioned. It remains to be seen how much will change in 2023, but the principal elements are clear.

In 973 at Bath Abbey, Edgar was crowned King of England by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Coronation service in use derives directly from that compiled by Dunstan over a thousand years ago. It has gone through several revisions or “recensions”, with the third being used through the later Middle Ages and (in translation) for the first four Stuarts. The last major revision was made in 1689 by William Compton, Bishop of London, for William III and Mary II, but it has been tweaked for each subsequent occasion, with new monarchs usually wanting a shorter ceremony than their predecessor’s, and new anthems or settings being commissioned. It remains to be seen how much will change in 2023, but the principal elements are clear.

The coronation is set within the Eucharist, as it has been since 973, and since 1689 most of the ceremonial has taken place after the sermon and Creed (though there has been no sermon since 1911). There are five main elements:

- The Recognition

- The Oath

- The Anointing

- The Investiture, culminating in the Crowning

- The Enthronement and Homage.

The coronation of a Queen Consort follows.

The service begins with the entrance procession. Since 1626, verses from Psalm 122 (“I was glad”) have been sung, and in 1902 Sir Hubert Parry incorporated into his setting the acclamation (“Vivat”) by the scholars of Westminster School. This setting is now an established tradition.

Next the Sovereign is introduced as the rightful monarch and acclaimed by the congregation, a vestige of the ancient election of the monarch. In 1953 the Oath was moved to follow this, having previously been at a later point. The monarch promises to preserve and protect the Church and to obey the laws of the land. In 1953 the Presentation of the Bible to the monarch was moved to this point having since its introduction in 1689 been immediately after the Crowning. Only when the Oath has been sworn and the Eucharist begun does the service move on to the Anointing. “Zadok the Priest” has been sung as an anthem here since 973, and Handel’s setting has been used since 1727. The sovereign moves to King Edward’s Chair (which holds the Stone of Scone) placed in the Crossing of the Abbey before the Altar, and is stripped. Under a canopy to protect their modesty, they are anointed in the form of a cross on the head, breast, and palms (in the reverse order in 1937 and 1953). Afterwards a white linen undergarment is put on, the Colobium Sindonis, and a golden robe, the Supertunica, and then the Investiture begins.

The regalia now used were largely made in 1660 for Charles II, the earlier items having been wantonly destroyed by the republican government of the Commonwealth. The ancient regalia, crowns, sceptres, rods and vestments, are thought to have been taken from the tomb of St Edward the Confessor when he was translated to a new shrine in 1269, and were used at every subsequent coronation at Westminster down to Charles I in 1626. These sacred items never left the Abbey, being deposited by the monarch at the end of the service, and a vestige of that tradition remains.

The Spurs are brought and touched to the monarch’s heels (in 1953 to the Queen’s hands), and then the king is girded with the Sword (in 1953 it was put in the Queen’s hands). He straightaway ungirds it and places it on the Altar as a gift to the Abbey. It is redeemed for 100 shillings and carried by one of the Peers.

Next come the Armills (bracelets) and Stole Royal. These were made in 1953 and their form and role has been unclear since the originals were lost in 1649. The sovereign is next vested with the Robe Royal, a great cloak of cloth of gold embroidered with roses, thistles, and shamrocks – and imperial Roman eagles, a reminder that from 973 the English were copying the symbolism of the Byzantine emperor.

Each stage of the investiture is accompanied by prayers. Since 1689 these prayers have careful to bless the person receiving each item, the monarch, rather than blessing the item itself.

The Orb – symbolizing the globe surmounted by the cross – is placed in the monarch’s hand, and immediately given back and replaced on the Altar. The ring, sapphire with a ruby cross, is put on the fourth (ring) finger of the monarch’s right hand. Historically the next item was the Crown, but since 1689 this has been the final item to be presented. Next comes the Sceptre, topped with a cross, and the Rod, with a dove standing on the cross at the top.

Finally, the culmination of the investiture, the monarch is crowned with St Edward’s Crown, made in 1660 to replace the lost crown taken from the saint’s tomb. The congregation acclaim the monarch “God save the King”, trumpets sound, and a gun salute is fired from the Tower of London.

After the Crowning the monarch is solemnly blessed by the Archbishop, and up to 1902 the Te Deum was sung at this point.

The sovereign now moves from King Edward’s Chair to the Throne to be enthroned there. The Archbishop and other bishops do their Fealty together, promising to be “faithful and true” and the Archbishop kisses the king’s left cheek. Then the royal dukes and the other peers pay their Homage and the leading peers kiss his cheek. Historically this has been a lengthy part of the service even when significantly shortened so that each degree (dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons) pays homage together, and might be further shortened in 2023.

The Queen’s Coronation follows, almost unchanged since that of Mary of Modena in 1685. She is anointed – in recent times only on the head, but up to 1761 on the head and breast, her apparel being opened for that purpose – invested with a ring, and then in a survival of the earlier order, crowned. Finally, she receives a sceptre and a rod, and is enthroned next to the king.

The Coronation itself is now complete and the Eucharist resumes at the offertory, including in 1953 a congregational hymn (Old 100th, “All people that on earth do dwell”), instead of an anthem. Traditionally the monarch makes an offering of the bread and wine, an altar-cloth and a pound-weight of gold, and a queen consort another altar-cloth and a “mark-weight” of gold.

The service follows the 1662 order, as it will in 2023, with the prayer for the Church militant, the General Confession and the Comfortable Words. The Sursum Corda is followed by a proper preface, Sanctus (sung to the melody of Merbecke in 1911 and 1937), Prayer of Humble Access, and Consecration. The Archbishop and assisting clergy receive Communion followed by the King and Queen. There is no general communion. The service continues with the Lord’s Prayer, post-communion (‘O Lord and heavenly Father’) and the Gloria. The monarch then moves into St Edward’s Chapel, where they are disrobed of their golden vestments – historically St Edward’s vestments and crown were not removed from the Abbey. Since 1911 the choir sings the Te Deum at this point. Finally, the monarch and consort process out through the Abbey to the west door, in velvet robes and the monarch wearing the Imperial State Crown.

For the text of the Coronation service, as used at each coronation from 1689 to 1953 see oremus.org/coronation

12 Comments

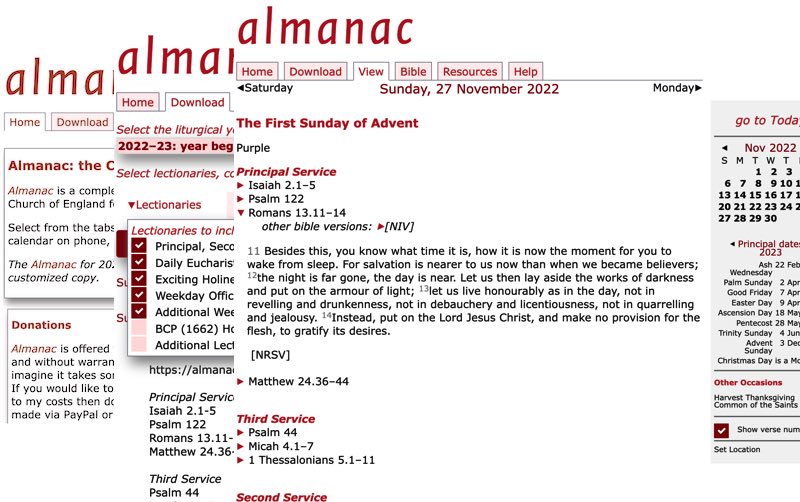

Common Worship Almanac for 2022-23

My Almanac for the liturgical year 2022–23, the year beginning Advent Sunday 2022 is now available. The Almanac is a complete and customizable download that can be added to the calendar on a desktop/laptop, a tablet or a smartphone providing a fully-worked out calendar and lectionary according to the rules of the Church of England. Several download formats are provided, giving access to most calendar software on most devices.

As before, download is free, and donations are invited.

What's new?

The Almanac is also available as a web page that can be installed as a web app on smartphones and tablets for easy access to all the data. New features include

- In the View tab you can toggle the display of verse numbers in the readings, making it simpler to copy and paste passages to other documents in the desired format.

- Following the new Royal Warrant, updated BCP and CW prayers for the King and Royal Family are linked in the Resources tab; Accession Day is now on 8 September, rather than 6 February.

- Although not strictly a CW or BCP observation, an entry is included this year for Coronation Day on 6 May 2023; it is expected that resources for public observance of the coronation will be produced, and this material will be added when it is available.

- Astronomical data (sunrise, sunset, moon rise and set and phase, solstices and equinoxes) is now fully working again, as is the separate Crosscal calendar download at crosscal.oremus.org.

Donations

This Almanac is offered free of charge, and without warranty, but as you might imagine it takes some effort to compile. If you would like to make a contribution to my costs then donations may be made via PayPal at paypal.me/simonkershaw. Alternatively, Amazon gift vouchers can be purchased online at Amazon (amazon.co.uk) for delivery by email to simon@kershaw.org.uk .

The Almanac has been freely available for over 20 years. There is not and has never been any charge for downloading and using the Almanac — this is just an opportunity to make a donation, if you so wish. Many thanks to those of you who have donated in the past or will do so this year, particularly those who regularly make a donation: your generosity is appreciated and makes the Almanac possible.

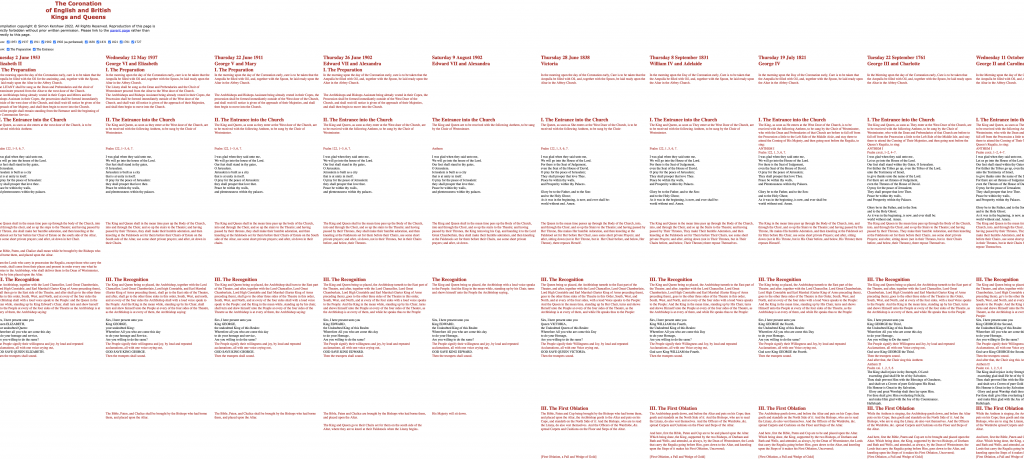

0 CommentsThe Coronation of English and British Kings and Queens

(Coronation of King George VI, 1937, painted by Frank Salisbury; Royal Collection Trust)

Beginning with the coronation of James I in 1603 there have been sixteen English-language coronations of English, or from 1714 British, monarchs. Before that, upto and including the coronation of Elizabeth I, the service had been conducted in Latin. The seventeenth, for King Charles III, is scheduled to take place on Saturday 6 May 2023.

As a small boy, over half a century ago, I was captivated by a souvenir of the 1937 coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth which belonged to my grandparents, and which contained the text of the service along with copious illustrations and some historical notes. From 1994 I have collected copies of the order of service of every coronation back to that of George IV in 1821, along with reproductions and editions of the earlier services back to 1603, as well as the music editions that have been published since 1902.

For some time I have thought of producing an historical edition of the coronation service with the different texts in parallel columns, making it easy to see the changes that have been made over the centuries. This is a bit complex to produce as a book (and perhaps not commercially viable) but a web page is easier to create, and can have other helpful features such as hiding or showing different sections of the page. So now there is a new page at oremus.org/coronation that contains the text of all the coronation services from 1953 back (currently) to that of George II in 1727. Work on adding earlier texts continues.

In each column the texts are aligned so that corresponding rubrics and spoken words match across the page. Individual columns can be hidden, making it easy to compare different years. Hiding rows, or sections of the text across all columns, is a feature that will be added soon.

The coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra scheduled for June 1902 was postponed because of the king’s illness. When it did take place in August, a number of modifications were made to place less stress on the convalescent king. Both the June and August texts are included in parallel columns.

With the Coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla scheduled for next year, I hope this will be a useful historical archive.

0 CommentsLiturgy at the Funeral of Queen Elizabeth II

The death of the head of state of a country is a significant event, even more so when that person has been head of state for 70 years, and is head of state of more than one country. The death of Queen Elizabeth II, guaranteed to come at some point, was nonetheless an event that touched many people, and millions if not billions of people around the world mourned her in some way.

The death of the head of state of a country is a significant event, even more so when that person has been head of state for 70 years, and is head of state of more than one country. The death of Queen Elizabeth II, guaranteed to come at some point, was nonetheless an event that touched many people, and millions if not billions of people around the world mourned her in some way.

For the first time, Orders of Service for the funeral at Westminster Abbey, and the Committal at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, were published online, enabling those watching on television to follow the text and join in if they desired.

For future reference, copies of these Orders of Service are attached to this post:

0 CommentsStations of the Cross

Stations of the Cross is a traditional devotion for Lent, and especially for Holy Week. It originated in Jersualem, where pilgrims would literally walk along the route from the centre of the city to the traditional place of Christ’s execution, stopping en route to recall various incidents recorded in the gospels, or elsewhere in the tradition. The number and names of the stations were later codified at fourteen (to which a fifteenth station of the Resurrection was added in more recent times). Many sets of words and prayers have been written to acccompany the walk. I compiled this particular set for an ecumenical service in my home parish, and subsequently published them on the Thinking Anglicans blog. It envisages a scenario in which some of those who participated in or witnessed the original events are gathered to remember what happened on that day.

- Pilate condemns Jesus to death

- Jesus takes up his cross

- Jesus falls the first time

- Jesus meets his mother

- Simon helps Jesus carry the cross

- Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

- Jesus falls the second time

- Jesus speaks to the women of Jerusalem

- Jesus falls the third time

- Jesus is stripped of his garments

- Jesus is nailed to the cross

- Jesus dies on the cross

- Jesus is taken down from the cross

- Jesus is placed in the tomb

- Jesus is risen

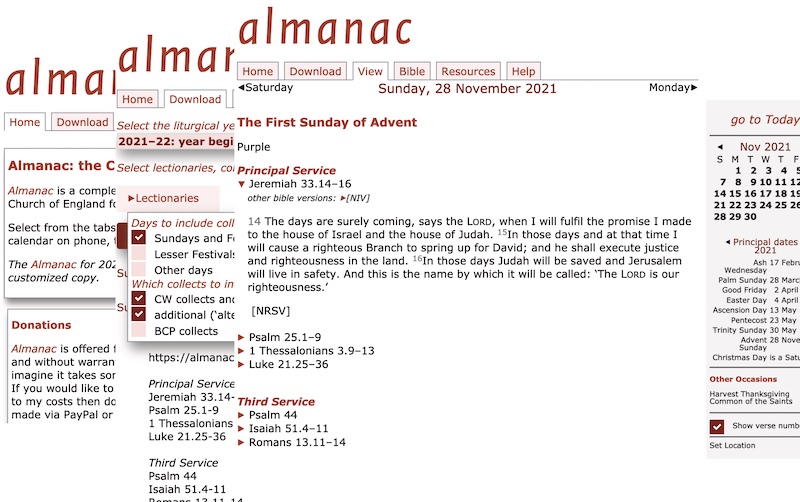

Common Worship Almanac for 2021-22

My Almanac for the liturgical year 2021–22, the year beginning Advent Sunday 2021 is now available. The Almanac is a complete and customizable download that can be added to the calendar on a desktop/laptop, a tablet or a smartphone providing a fully-worked out calendar and lectionary according to the rules of the Church of England. Several download formats are provided, giving access to most calendar software on most devices.

As before, download is free, and donations are invited.

What's new?

The Almanac is also available as a web page that can be installed as a web app on smartphones and tablets for easy access to all the data. New features include

- the Download tab now shows a live preview of the data that will be added to your calendar; as you select options from the menus the live preview automatically reflects your choices

- in the View tab you can toggle the display of verse numbers in the readings, making it simpler to copy and paste passages to other documents in the desired format

- in the View tab the bible readings now have an additional link to the NIV text at Bible Gateway, as well as displaying the NRSV text (or the Common Worship psalter for psalms)

- a new shorter format for subscription links (old-style links continue to work as well)

Donations

This Almanac is offered free of charge, and without warranty, but as you might imagine it takes some effort to compile. If you would like to make a contribution to my costs then donations may be made via PayPal at paypal.me/simonkershaw. Alternatively, Amazon gift vouchers can be purchased online at Amazon (amazon.co.uk) for delivery by email to simon@kershaw.org.uk .

The Almanac has been freely available for over 20 years. There is not and has never been any charge for downloading and using the Almanac — this is just an opportunity to make a donation, if you so wish. Many thanks to those of you who have donated in the past or will do so this year, particularly those who regularly make a donation: your generosity is appreciated and makes the Almanac possible.

0 Comments