The Coronation Liturgy

This is a longer version of an article published in Praxis News of Worship, March 2023.

In 973 at Bath Abbey, Edgar was crowned King of England by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Coronation service in use derives directly from that compiled by Dunstan over a thousand years ago. It has gone through several revisions or “recensions”, with the third being used through the later Middle Ages and (in translation) for the first four Stuarts. The last major revision was made in 1689 by William Compton, Bishop of London, for William III and Mary II, but it has been tweaked for each subsequent occasion, with new monarchs usually wanting a shorter ceremony than their predecessor’s, and new anthems or settings being commissioned. It remains to be seen how much will change in 2023, but the principal elements are clear.

In 973 at Bath Abbey, Edgar was crowned King of England by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Coronation service in use derives directly from that compiled by Dunstan over a thousand years ago. It has gone through several revisions or “recensions”, with the third being used through the later Middle Ages and (in translation) for the first four Stuarts. The last major revision was made in 1689 by William Compton, Bishop of London, for William III and Mary II, but it has been tweaked for each subsequent occasion, with new monarchs usually wanting a shorter ceremony than their predecessor’s, and new anthems or settings being commissioned. It remains to be seen how much will change in 2023, but the principal elements are clear.

The coronation is set within the Eucharist, as it has been since 973, and since 1689 most of the ceremonial has taken place after the sermon and Creed (though there has been no sermon since 1911). There are five main elements:

- The Recognition

- The Oath

- The Anointing

- The Investiture, culminating in the Crowning

- The Enthronement and Homage.

The coronation of a Queen Consort follows.

The service begins with the entrance procession. Since 1626, verses from Psalm 122 (“I was glad”) have been sung, and in 1902 Sir Hubert Parry incorporated into his setting the acclamation (“Vivat”) by the scholars of Westminster School. This setting is now an established tradition.

Next the Sovereign is introduced as the rightful monarch and acclaimed by the congregation, a vestige of the ancient election of the monarch. In 1953 the Oath was moved to follow this, having previously been at a later point. The monarch promises to preserve and protect the Church and to obey the laws of the land. In 1953 the Presentation of the Bible to the monarch was moved to this point having since its introduction in 1689 been immediately after the Crowning. Only when the Oath has been sworn and the Eucharist begun does the service move on to the Anointing. “Zadok the Priest” has been sung as an anthem here since 973, and Handel’s setting has been used since 1727. The sovereign moves to King Edward’s Chair (which holds the Stone of Scone) placed in the Crossing of the Abbey before the Altar, and is stripped. Under a canopy to protect their modesty, they are anointed in the form of a cross on the head, breast, and palms (in the reverse order in 1937 and 1953). Afterwards a white linen undergarment is put on, the Colobium Sindonis, and a golden robe, the Supertunica, and then the Investiture begins.

The regalia now used were largely made in 1660 for Charles II, the earlier items having been wantonly destroyed by the republican government of the Commonwealth. The ancient regalia, crowns, sceptres, rods and vestments, are thought to have been taken from the tomb of St Edward the Confessor when he was translated to a new shrine in 1269, and were used at every subsequent coronation at Westminster down to Charles I in 1626. These sacred items never left the Abbey, being deposited by the monarch at the end of the service, and a vestige of that tradition remains.

The Spurs are brought and touched to the monarch’s heels (in 1953 to the Queen’s hands), and then the king is girded with the Sword (in 1953 it was put in the Queen’s hands). He straightaway ungirds it and places it on the Altar as a gift to the Abbey. It is redeemed for 100 shillings and carried by one of the Peers.

Next come the Armills (bracelets) and Stole Royal. These were made in 1953 and their form and role has been unclear since the originals were lost in 1649. The sovereign is next vested with the Robe Royal, a great cloak of cloth of gold embroidered with roses, thistles, and shamrocks – and imperial Roman eagles, a reminder that from 973 the English were copying the symbolism of the Byzantine emperor.

Each stage of the investiture is accompanied by prayers. Since 1689 these prayers have careful to bless the person receiving each item, the monarch, rather than blessing the item itself.

The Orb – symbolizing the globe surmounted by the cross – is placed in the monarch’s hand, and immediately given back and replaced on the Altar. The ring, sapphire with a ruby cross, is put on the fourth (ring) finger of the monarch’s right hand. Historically the next item was the Crown, but since 1689 this has been the final item to be presented. Next comes the Sceptre, topped with a cross, and the Rod, with a dove standing on the cross at the top.

Finally, the culmination of the investiture, the monarch is crowned with St Edward’s Crown, made in 1660 to replace the lost crown taken from the saint’s tomb. The congregation acclaim the monarch “God save the King”, trumpets sound, and a gun salute is fired from the Tower of London.

After the Crowning the monarch is solemnly blessed by the Archbishop, and up to 1902 the Te Deum was sung at this point.

The sovereign now moves from King Edward’s Chair to the Throne to be enthroned there. The Archbishop and other bishops do their Fealty together, promising to be “faithful and true” and the Archbishop kisses the king’s left cheek. Then the royal dukes and the other peers pay their Homage and the leading peers kiss his cheek. Historically this has been a lengthy part of the service even when significantly shortened so that each degree (dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons) pays homage together, and might be further shortened in 2023.

The Queen’s Coronation follows, almost unchanged since that of Mary of Modena in 1685. She is anointed – in recent times only on the head, but up to 1761 on the head and breast, her apparel being opened for that purpose – invested with a ring, and then in a survival of the earlier order, crowned. Finally, she receives a sceptre and a rod, and is enthroned next to the king.

The Coronation itself is now complete and the Eucharist resumes at the offertory, including in 1953 a congregational hymn (Old 100th, “All people that on earth do dwell”), instead of an anthem. Traditionally the monarch makes an offering of the bread and wine, an altar-cloth and a pound-weight of gold, and a queen consort another altar-cloth and a “mark-weight” of gold.

The service follows the 1662 order, as it will in 2023, with the prayer for the Church militant, the General Confession and the Comfortable Words. The Sursum Corda is followed by a proper preface, Sanctus (sung to the melody of Merbecke in 1911 and 1937), Prayer of Humble Access, and Consecration. The Archbishop and assisting clergy receive Communion followed by the King and Queen. There is no general communion. The service continues with the Lord’s Prayer, post-communion (‘O Lord and heavenly Father’) and the Gloria. The monarch then moves into St Edward’s Chapel, where they are disrobed of their golden vestments – historically St Edward’s vestments and crown were not removed from the Abbey. Since 1911 the choir sings the Te Deum at this point. Finally, the monarch and consort process out through the Abbey to the west door, in velvet robes and the monarch wearing the Imperial State Crown.

For the text of the Coronation service, as used at each coronation from 1689 to 1953 see oremus.org/coronation

13 Comments

Common Worship Almanac for 2022-23

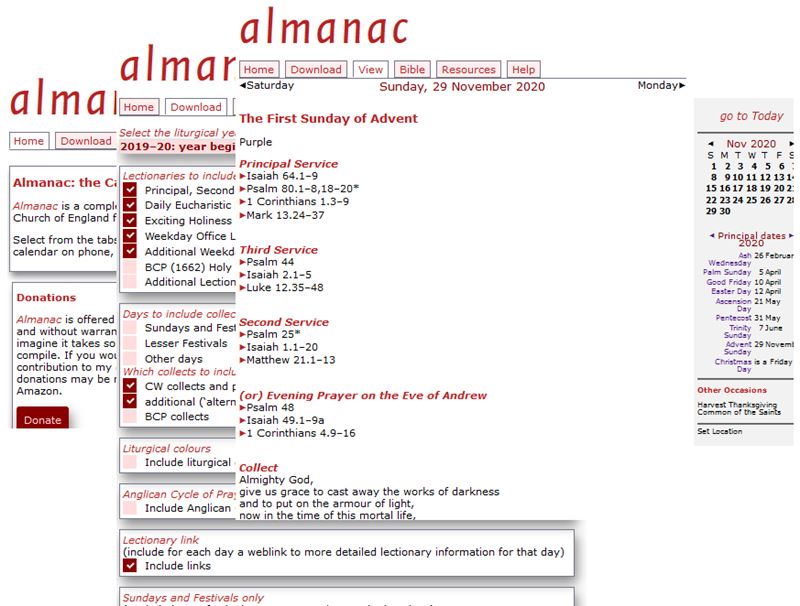

My Almanac for the liturgical year 2022–23, the year beginning Advent Sunday 2022 is now available. The Almanac is a complete and customizable download that can be added to the calendar on a desktop/laptop, a tablet or a smartphone providing a fully-worked out calendar and lectionary according to the rules of the Church of England. Several download formats are provided, giving access to most calendar software on most devices.

As before, download is free, and donations are invited.

What's new?

The Almanac is also available as a web page that can be installed as a web app on smartphones and tablets for easy access to all the data. New features include

- In the View tab you can toggle the display of verse numbers in the readings, making it simpler to copy and paste passages to other documents in the desired format.

- Following the new Royal Warrant, updated BCP and CW prayers for the King and Royal Family are linked in the Resources tab; Accession Day is now on 8 September, rather than 6 February.

- Although not strictly a CW or BCP observation, an entry is included this year for Coronation Day on 6 May 2023; it is expected that resources for public observance of the coronation will be produced, and this material will be added when it is available.

- Astronomical data (sunrise, sunset, moon rise and set and phase, solstices and equinoxes) is now fully working again, as is the separate Crosscal calendar download at crosscal.oremus.org.

Donations

This Almanac is offered free of charge, and without warranty, but as you might imagine it takes some effort to compile. If you would like to make a contribution to my costs then donations may be made via PayPal at paypal.me/simonkershaw. Alternatively, Amazon gift vouchers can be purchased online at Amazon (amazon.co.uk) for delivery by email to simon@kershaw.org.uk .

The Almanac has been freely available for over 20 years. There is not and has never been any charge for downloading and using the Almanac — this is just an opportunity to make a donation, if you so wish. Many thanks to those of you who have donated in the past or will do so this year, particularly those who regularly make a donation: your generosity is appreciated and makes the Almanac possible.

0 CommentsThe Coronation of English and British Kings and Queens

(Coronation of King George VI, 1937, painted by Frank Salisbury; Royal Collection Trust)

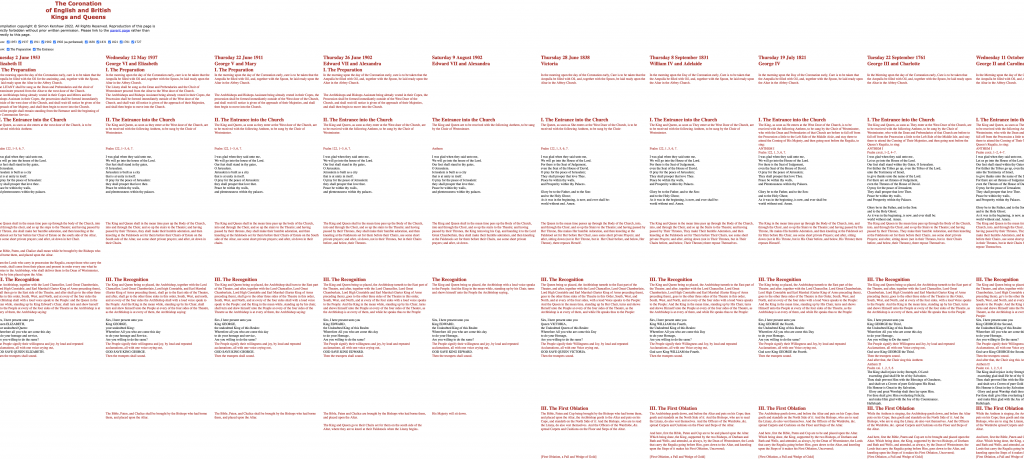

Beginning with the coronation of James I in 1603 there have been sixteen English-language coronations of English, or from 1714 British, monarchs. Before that, upto and including the coronation of Elizabeth I, the service had been conducted in Latin. The seventeenth, for King Charles III, is scheduled to take place on Saturday 6 May 2023.

As a small boy, over half a century ago, I was captivated by a souvenir of the 1937 coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth which belonged to my grandparents, and which contained the text of the service along with copious illustrations and some historical notes. From 1994 I have collected copies of the order of service of every coronation back to that of George IV in 1821, along with reproductions and editions of the earlier services back to 1603, as well as the music editions that have been published since 1902.

For some time I have thought of producing an historical edition of the coronation service with the different texts in parallel columns, making it easy to see the changes that have been made over the centuries. This is a bit complex to produce as a book (and perhaps not commercially viable) but a web page is easier to create, and can have other helpful features such as hiding or showing different sections of the page. So now there is a new page at oremus.org/coronation that contains the text of all the coronation services from 1953 back (currently) to that of George II in 1727. Work on adding earlier texts continues.

In each column the texts are aligned so that corresponding rubrics and spoken words match across the page. Individual columns can be hidden, making it easy to compare different years. Hiding rows, or sections of the text across all columns, is a feature that will be added soon.

The coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra scheduled for June 1902 was postponed because of the king’s illness. When it did take place in August, a number of modifications were made to place less stress on the convalescent king. Both the June and August texts are included in parallel columns.

With the Coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla scheduled for next year, I hope this will be a useful historical archive.

0 CommentsLiturgy at the Funeral of Queen Elizabeth II

The death of the head of state of a country is a significant event, even more so when that person has been head of state for 70 years, and is head of state of more than one country. The death of Queen Elizabeth II, guaranteed to come at some point, was nonetheless an event that touched many people, and millions if not billions of people around the world mourned her in some way.

The death of the head of state of a country is a significant event, even more so when that person has been head of state for 70 years, and is head of state of more than one country. The death of Queen Elizabeth II, guaranteed to come at some point, was nonetheless an event that touched many people, and millions if not billions of people around the world mourned her in some way.

For the first time, Orders of Service for the funeral at Westminster Abbey, and the Committal at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, were published online, enabling those watching on television to follow the text and join in if they desired.

For future reference, copies of these Orders of Service are attached to this post:

0 CommentsStations of the Cross

Stations of the Cross is a traditional devotion for Lent, and especially for Holy Week. It originated in Jersualem, where pilgrims would literally walk along the route from the centre of the city to the traditional place of Christ’s execution, stopping en route to recall various incidents recorded in the gospels, or elsewhere in the tradition. The number and names of the stations were later codified at fourteen (to which a fifteenth station of the Resurrection was added in more recent times). Many sets of words and prayers have been written to acccompany the walk. I compiled this particular set for an ecumenical service in my home parish, and subsequently published them on the Thinking Anglicans blog. It envisages a scenario in which some of those who participated in or witnessed the original events are gathered to remember what happened on that day.

- Pilate condemns Jesus to death

- Jesus takes up his cross

- Jesus falls the first time

- Jesus meets his mother

- Simon helps Jesus carry the cross

- Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

- Jesus falls the second time

- Jesus speaks to the women of Jerusalem

- Jesus falls the third time

- Jesus is stripped of his garments

- Jesus is nailed to the cross

- Jesus dies on the cross

- Jesus is taken down from the cross

- Jesus is placed in the tomb

- Jesus is risen

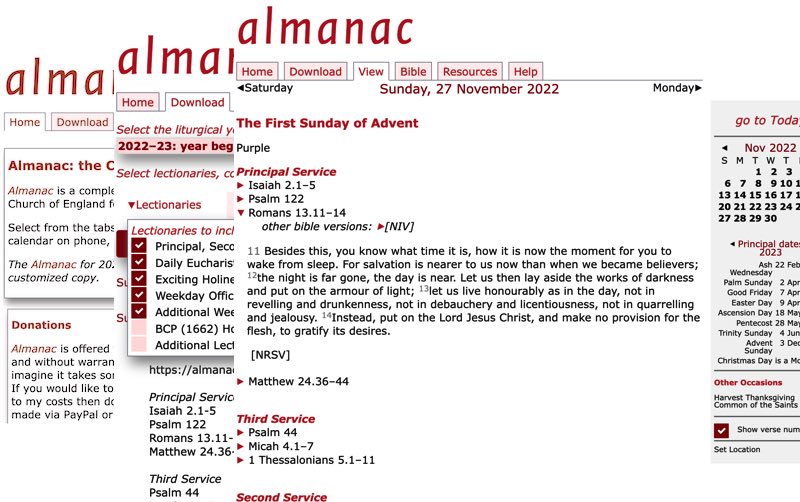

Common Worship Almanac for 2021-22

My Almanac for the liturgical year 2021–22, the year beginning Advent Sunday 2021 is now available. The Almanac is a complete and customizable download that can be added to the calendar on a desktop/laptop, a tablet or a smartphone providing a fully-worked out calendar and lectionary according to the rules of the Church of England. Several download formats are provided, giving access to most calendar software on most devices.

As before, download is free, and donations are invited.

What's new?

The Almanac is also available as a web page that can be installed as a web app on smartphones and tablets for easy access to all the data. New features include

- the Download tab now shows a live preview of the data that will be added to your calendar; as you select options from the menus the live preview automatically reflects your choices

- in the View tab you can toggle the display of verse numbers in the readings, making it simpler to copy and paste passages to other documents in the desired format

- in the View tab the bible readings now have an additional link to the NIV text at Bible Gateway, as well as displaying the NRSV text (or the Common Worship psalter for psalms)

- a new shorter format for subscription links (old-style links continue to work as well)

Donations

This Almanac is offered free of charge, and without warranty, but as you might imagine it takes some effort to compile. If you would like to make a contribution to my costs then donations may be made via PayPal at paypal.me/simonkershaw. Alternatively, Amazon gift vouchers can be purchased online at Amazon (amazon.co.uk) for delivery by email to simon@kershaw.org.uk .

The Almanac has been freely available for over 20 years. There is not and has never been any charge for downloading and using the Almanac — this is just an opportunity to make a donation, if you so wish. Many thanks to those of you who have donated in the past or will do so this year, particularly those who regularly make a donation: your generosity is appreciated and makes the Almanac possible.

0 CommentsAn act of iconoclasm

There’s lots of talk at the moment of toppling statues and removing items commemorating historical figures with what is now seen as a dubious past. Here is a little story that has never been told before.

In June 1980, 41 years ago, I was an undergraduate at Wadham College, right at the end of my three years at Oxford. I lived in a room in a small courtyard on top of the then-new college library. The library, opened three years earlier, had been significantly funded by a donation from the Iranian imperial family, and was named after the twin sister of the Shah, Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, and there was a plaque commemorating this dedication over the inside of the main entrance. The funding and the dedication had been fiercely criticised by the student body and others, and a number of protests took place while I was at the college. In February 1979 the Shah had been overthrown and had gone into exile, as had his sister, but the library dedication remained, and so did the plaque.

Although not to everyone’s architectural taste, I liked the new library building (by Glasgow architect Andy MacMillan of Gillespie, Kidd and Coia), and knew every public corner of it. There were also parts that were out of bounds to undergraduates, and eventually I discovered that at the dead of night when there was no one else around then you could venture unchallenged through any “no entry” signs or unlocked doors. In particular, there was a spiral staircase leading from the downstairs reading lounge up to the limited-access Persian section. The Persian section had another access door from the floor on which it was, but my recollection is that that door was normally locked.

It was during one of these night-time explorations that I discovered (as you do) that the Pahlavi plaque over the main door was very simply fixed to the library wall, with just a couple of keyhole slots on the back that fitted over some screws in the library wall.

And so an idea formed in my mind, as I was nearing finals that June. Wouldn’t it be fun, I thought, to remove the plaque? But how to dispose of it? The idea sat in my head for a few weeks as I revised and sat my finals. Many subjects held their finals early in the summer term, but for my subject, physics, finals were right at the end of term, and afterwards nearly all undergraduates left Oxford. I had already arranged to stay in college for a few more days.

One night after the end of term, when all was quiet, I went downstairs from my room into the library. I walked all round to be sure that there was no one else in the library, and I checked the place where I had thought of putting the plaque. All was deserted. Back at the entrance I reached up and gently lifted the plaque from off the wall over the door. It was about 3 feet or so long, 10 inches high and perhaps an inch or two deep, solid oak and moderately heavy. Across the library and up the spiral staircase, and I was into the closed Persian section. The bookcases here were tall, over 6 feet, and I carefully placed the plaque on top of one, where it could not be seen from below, and where it was not possible to look down from above. Or, and here my memory is a little hazy after all these years, did I come out of the Persian section and into the upper level of the library and place it on top of a bookcase there? Either way, it would not be found accidentally.

Was it a protest at the Iranian regime, or a student prank? A little bit of both I suppose. I had thought of putting a sign in its place with words such as “the Ayatollah Khomeini Library” – that would certainly have made it a prank in my eyes, but I didn’t carry through with that.

It was a couple of months later, in mid-September, during the long summer vac, and before I started my first job, that I returned to Oxford for a few days. Wandering round the college I bumped into the chaplain (Peter Allan, later a monk at Mirfield) and we arranged to have lunch the next day, at the Trout at Wolvercote, if I recall correctly, or was it the Perch at Binsey? “Did you hear,” he asked me, “that someone had removed the Pahlavi plaque from the library, and it had disappeared?” “And what,” I said as innocently as I could, “is the college doing about it?” “They’re just relieved that they don’t have to decide what to do with it,” he replied. So much, I thought, for my little act of rebellion. But I stayed silent. And I have stayed silent until today.

I’ve never heard whether the plaque was found, though some time later I left a note in the library saying where I had put it. Several years later the library was renamed the Ferdowsi Library after the Persian poet Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi (c.940‑1020), a much less divisive figure.

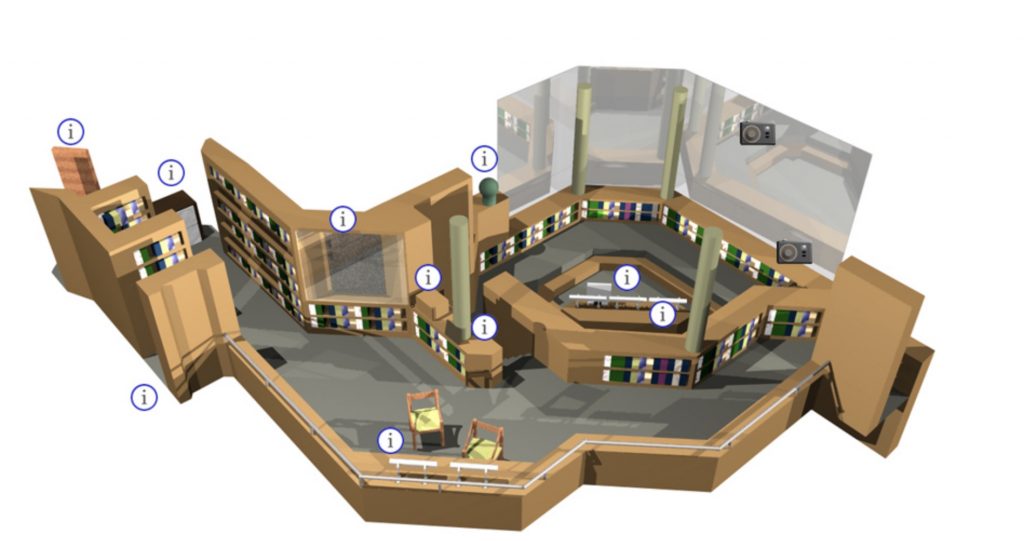

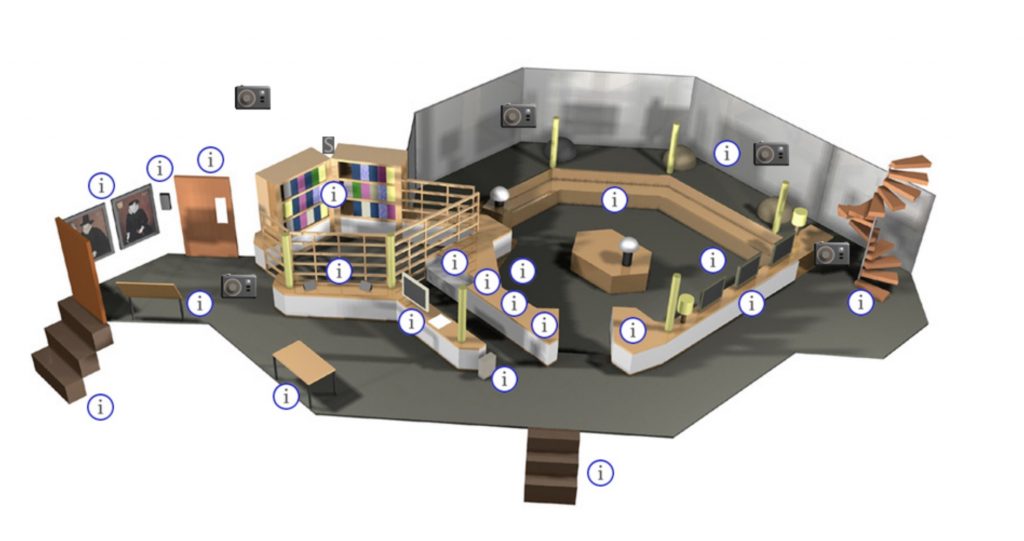

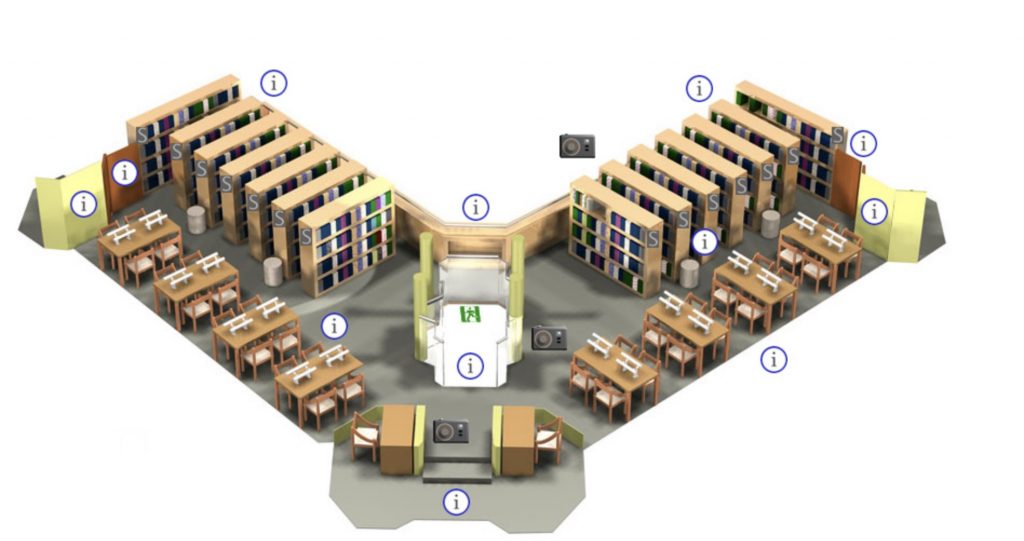

This diagrammatic view of the library shows how the different levels interact (and the default view shows the entrance door, over which the plaque was sited, and the spiral staircase up to the Persian section)

https://weblearn.ox.ac.uk/…/virtualtour/mezzanine.html

These pictures show the exterior and inside of the library, and apart from the presence of computers, it was pretty much the same in 1980.

https://www.wadham.ox.ac.uk/…/a‑day-in-the-life-of…

Two further links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_MacMillan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashraf_Pahlavi

Little Gidding Pilgrimage 2020

Each year the Friends of Little Gidding, of which I am the Chair, organizes a Pilgrimage to Little Gidding. For the last few years this has taken the form of a walk from Leighton Bromswold to Little Gidding, with stops (or ‘stations’) for short reflections along the way. The day begins with a celebration of the Eucharist at Leighton Bromswold, and ends with Evensong at Little Gidding followed by Tea.

The events of 2020 made this format impossible, and instead we held an online event with a number of pre-recorded segments and some ‘live’ readings and prayers, as well as a little interaction between those taking part. Follow me as I walk from Leighton Bromswold to Little Gidding, introducing the various stopping points, and talking about the Ferrars’ experience of the devastating plague that hit London in 1625, and that forced them to leave the City and move to Little Gidding, while Fiona Brampton, Chaplain at Little Gidding, reflects on the impact of COVID-19 on us today.

Footage of me and video editing by Alexander Kershaw. Footage of Fiona filmed on my iPhone, and edited into the video by me, along with ‘live’ readings and prayers recorded via Zoom.

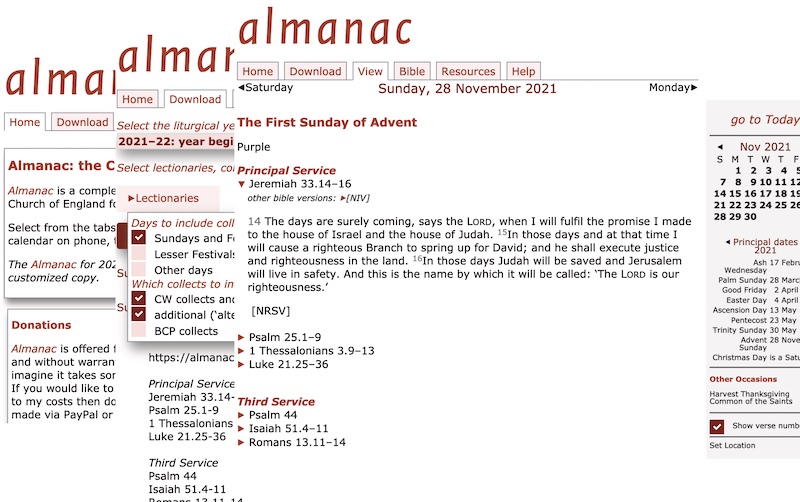

0 Comments2020-21 Almanac for Common Worship and BCP

Now available for the year beginning Advent Sunday 2020: Almanac, the calendar, lectionary and collects according to the calendar of the Church of England, for Common Worship and for the Book of Common Prayer. Download to your calendar or use the web app.

Download is free, donations are invited.

What's new?

The Almanac web page has been comprehensively updated since last year to make it easier and more useful. Updates include

- the download page and the daily view have been integrated into a single tabbed page

- the oremus Bible Browser (which includes the full NRSV, the AV, and the psalters from the prayer book and Common Worship) is added on another tab

- a resources tab provides direct links to all the official Common Worship texts, hymn suggestions (with links through to HymnQuest) and some other liturgical resources

- the Almanac daily view includes sunrise and sunset times, which can be customized to your location

- on phones and tablets you can add an Almanac icon or tile to your screen so that it is accessible like an app (details in the Help tab), and you can swipe forwards and backwards through the days, and through bible passages in the Bible tab

As usual, the Almanac is available in a number of formats for adding to Microsoft Outlook, Apple Calendar, iPhone or iPad, Google Calendar and other calendar applications. It can be synced from a desktop calendar to a tablet or smartphone (including Apple iPads and iPhones, Android phones and tablets, and Windows Surface tablets). There is also a csv format, which can be opened in a spreadsheet for further manipulation.

Naturally I hope that the Almanac is free of errors, but I disclaim responsibility for the effects of any errors. My liability is limited to providing a corrected file for import, at my own convenience. Please help by notifying me of possible errors.

Donations

This Almanac is offered free of charge, and without warranty, but as you might imagine it takes some effort to compile. If you would like to make a contribution to my costs then donations may be made via PayPal at paypal.me/simonkershaw. Alternatively, Amazon gift vouchers can be purchased online at Amazon (amazon.co.uk) for delivery by email to simon@kershaw.org.uk .

The Almanac web page carries the date 8 September 2000, so, as the Beatles sang, “it was twenty years ago” that I first provided a digital liturgical calendar, which in a couple of years evolved into a fully worked-out lectionary. There is not and has never been any charge for downloading and using the Almanac — this is just an opportunity to make a donation, if you so wish. Many thanks to those of you who have donated in the past or will do so this year, particularly those who regularly make a donation: your generosity is appreciated and makes the Almanac possible.

1 Comment

Are individual cups legal for communion?

Since March, the Church of England guidance issued by the bishops has stipulated that communion should be received “in one kind” only, and that the chalice, the common cup, should be withheld from all except the priest taking the service. This has been backed by legal advice that a single cup must be used, and if it is impossible to share a common cup, then the cup should be withheld.

Now a group of barristers has challenged this legal advice that it is unlawful to use separate individual cups, issuing a contrary legal opinion that the overriding priority is that communion should be administered in both kinds, and that this should allow individual cups to be used.

The Church Times reports on this story here.

0 Comments