Coronation Liturgy Talk

(The Coronation of Queen Victoria, 1838, painted by Sir George Hayter; Royal Collection Trust)

Last week I participated in a “colloquium” organized by Praxis on the subject of the Coronation, giving an introductory talk on the elements of the service or liturgy at previous coronations. (We don’t yet have details of the 2023 service.) The other major presenter was the Very Revd Dr David Hoyle, the Dean of Westminster, who is closely involved in the planning and will be a major participant at the service.

The slides I used at that talk can be found here, in two versions – a large illustrated version and a small version with no illustrations.

- illustrated PowerPoint (126MB); PDF (1.2MB); PDF with notes (588kB)

- text only PowerPoint (100kB)

Both versions contain some notes, and they can also be read in conjunction with my earlier post on the Coronation liturgy.

Additionally a recording of the colloquium is available on YouTube. My section starts at about 7 minutes in – do watch all the recording if you have time.

0 Comments

The Coronation Oil

The oil that will be used to anoint the king and queen at their coronation on 6 May has been consecrated in Jerusalem by the Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and the Anglican Archbishop. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s website reports the details here, and that article is archived below.

0 CommentsThe Coronation Liturgy

This is a longer version of an article published in Praxis News of Worship, March 2023.

In 973 at Bath Abbey, Edgar was crowned King of England by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Coronation service in use derives directly from that compiled by Dunstan over a thousand years ago. It has gone through several revisions or “recensions”, with the third being used through the later Middle Ages and (in translation) for the first four Stuarts. The last major revision was made in 1689 by William Compton, Bishop of London, for William III and Mary II, but it has been tweaked for each subsequent occasion, with new monarchs usually wanting a shorter ceremony than their predecessor’s, and new anthems or settings being commissioned. It remains to be seen how much will change in 2023, but the principal elements are clear.

In 973 at Bath Abbey, Edgar was crowned King of England by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Coronation service in use derives directly from that compiled by Dunstan over a thousand years ago. It has gone through several revisions or “recensions”, with the third being used through the later Middle Ages and (in translation) for the first four Stuarts. The last major revision was made in 1689 by William Compton, Bishop of London, for William III and Mary II, but it has been tweaked for each subsequent occasion, with new monarchs usually wanting a shorter ceremony than their predecessor’s, and new anthems or settings being commissioned. It remains to be seen how much will change in 2023, but the principal elements are clear.

The coronation is set within the Eucharist, as it has been since 973, and since 1689 most of the ceremonial has taken place after the sermon and Creed (though there has been no sermon since 1911). There are five main elements:

- The Recognition

- The Oath

- The Anointing

- The Investiture, culminating in the Crowning

- The Enthronement and Homage.

The coronation of a Queen Consort follows.

The service begins with the entrance procession. Since 1626, verses from Psalm 122 (“I was glad”) have been sung, and in 1902 Sir Hubert Parry incorporated into his setting the acclamation (“Vivat”) by the scholars of Westminster School. This setting is now an established tradition.

Next the Sovereign is introduced as the rightful monarch and acclaimed by the congregation, a vestige of the ancient election of the monarch. In 1953 the Oath was moved to follow this, having previously been at a later point. The monarch promises to preserve and protect the Church and to obey the laws of the land. In 1953 the Presentation of the Bible to the monarch was moved to this point having since its introduction in 1689 been immediately after the Crowning. Only when the Oath has been sworn and the Eucharist begun does the service move on to the Anointing. “Zadok the Priest” has been sung as an anthem here since 973, and Handel’s setting has been used since 1727. The sovereign moves to King Edward’s Chair (which holds the Stone of Scone) placed in the Crossing of the Abbey before the Altar, and is stripped. Under a canopy to protect their modesty, they are anointed in the form of a cross on the head, breast, and palms (in the reverse order in 1937 and 1953). Afterwards a white linen undergarment is put on, the Colobium Sindonis, and a golden robe, the Supertunica, and then the Investiture begins.

The regalia now used were largely made in 1660 for Charles II, the earlier items having been wantonly destroyed by the republican government of the Commonwealth. The ancient regalia, crowns, sceptres, rods and vestments, are thought to have been taken from the tomb of St Edward the Confessor when he was translated to a new shrine in 1269, and were used at every subsequent coronation at Westminster down to Charles I in 1626. These sacred items never left the Abbey, being deposited by the monarch at the end of the service, and a vestige of that tradition remains.

The Spurs are brought and touched to the monarch’s heels (in 1953 to the Queen’s hands), and then the king is girded with the Sword (in 1953 it was put in the Queen’s hands). He straightaway ungirds it and places it on the Altar as a gift to the Abbey. It is redeemed for 100 shillings and carried by one of the Peers.

Next come the Armills (bracelets) and Stole Royal. These were made in 1953 and their form and role has been unclear since the originals were lost in 1649. The sovereign is next vested with the Robe Royal, a great cloak of cloth of gold embroidered with roses, thistles, and shamrocks – and imperial Roman eagles, a reminder that from 973 the English were copying the symbolism of the Byzantine emperor.

Each stage of the investiture is accompanied by prayers. Since 1689 these prayers have careful to bless the person receiving each item, the monarch, rather than blessing the item itself.

The Orb – symbolizing the globe surmounted by the cross – is placed in the monarch’s hand, and immediately given back and replaced on the Altar. The ring, sapphire with a ruby cross, is put on the fourth (ring) finger of the monarch’s right hand. Historically the next item was the Crown, but since 1689 this has been the final item to be presented. Next comes the Sceptre, topped with a cross, and the Rod, with a dove standing on the cross at the top.

Finally, the culmination of the investiture, the monarch is crowned with St Edward’s Crown, made in 1660 to replace the lost crown taken from the saint’s tomb. The congregation acclaim the monarch “God save the King”, trumpets sound, and a gun salute is fired from the Tower of London.

After the Crowning the monarch is solemnly blessed by the Archbishop, and up to 1902 the Te Deum was sung at this point.

The sovereign now moves from King Edward’s Chair to the Throne to be enthroned there. The Archbishop and other bishops do their Fealty together, promising to be “faithful and true” and the Archbishop kisses the king’s left cheek. Then the royal dukes and the other peers pay their Homage and the leading peers kiss his cheek. Historically this has been a lengthy part of the service even when significantly shortened so that each degree (dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons) pays homage together, and might be further shortened in 2023.

The Queen’s Coronation follows, almost unchanged since that of Mary of Modena in 1685. She is anointed – in recent times only on the head, but up to 1761 on the head and breast, her apparel being opened for that purpose – invested with a ring, and then in a survival of the earlier order, crowned. Finally, she receives a sceptre and a rod, and is enthroned next to the king.

The Coronation itself is now complete and the Eucharist resumes at the offertory, including in 1953 a congregational hymn (Old 100th, “All people that on earth do dwell”), instead of an anthem. Traditionally the monarch makes an offering of the bread and wine, an altar-cloth and a pound-weight of gold, and a queen consort another altar-cloth and a “mark-weight” of gold.

The service follows the 1662 order, as it will in 2023, with the prayer for the Church militant, the General Confession and the Comfortable Words. The Sursum Corda is followed by a proper preface, Sanctus (sung to the melody of Merbecke in 1911 and 1937), Prayer of Humble Access, and Consecration. The Archbishop and assisting clergy receive Communion followed by the King and Queen. There is no general communion. The service continues with the Lord’s Prayer, post-communion (‘O Lord and heavenly Father’) and the Gloria. The monarch then moves into St Edward’s Chapel, where they are disrobed of their golden vestments – historically St Edward’s vestments and crown were not removed from the Abbey. Since 1911 the choir sings the Te Deum at this point. Finally, the monarch and consort process out through the Abbey to the west door, in velvet robes and the monarch wearing the Imperial State Crown.

For the text of the Coronation service, as used at each coronation from 1689 to 1953 see oremus.org/coronation

13 Comments

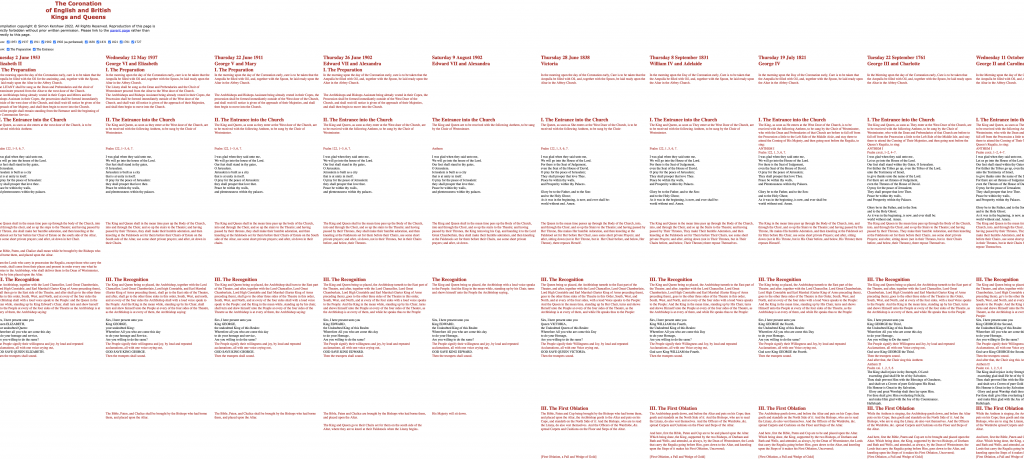

The Coronation of English and British Kings and Queens

(Coronation of King George VI, 1937, painted by Frank Salisbury; Royal Collection Trust)

Beginning with the coronation of James I in 1603 there have been sixteen English-language coronations of English, or from 1714 British, monarchs. Before that, upto and including the coronation of Elizabeth I, the service had been conducted in Latin. The seventeenth, for King Charles III, is scheduled to take place on Saturday 6 May 2023.

As a small boy, over half a century ago, I was captivated by a souvenir of the 1937 coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth which belonged to my grandparents, and which contained the text of the service along with copious illustrations and some historical notes. From 1994 I have collected copies of the order of service of every coronation back to that of George IV in 1821, along with reproductions and editions of the earlier services back to 1603, as well as the music editions that have been published since 1902.

For some time I have thought of producing an historical edition of the coronation service with the different texts in parallel columns, making it easy to see the changes that have been made over the centuries. This is a bit complex to produce as a book (and perhaps not commercially viable) but a web page is easier to create, and can have other helpful features such as hiding or showing different sections of the page. So now there is a new page at oremus.org/coronation that contains the text of all the coronation services from 1953 back (currently) to that of George II in 1727. Work on adding earlier texts continues.

In each column the texts are aligned so that corresponding rubrics and spoken words match across the page. Individual columns can be hidden, making it easy to compare different years. Hiding rows, or sections of the text across all columns, is a feature that will be added soon.

The coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra scheduled for June 1902 was postponed because of the king’s illness. When it did take place in August, a number of modifications were made to place less stress on the convalescent king. Both the June and August texts are included in parallel columns.

With the Coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla scheduled for next year, I hope this will be a useful historical archive.

0 Comments