Heraldic Glass at Little Gidding

Little Gidding is a place with which I have a long association. It gave its name to TS Eliot’s last great poem and before that in the early 17th century Nicholas Ferrar and his extended family lived there in a household of prayer and work. Eliot famously described the tiny church at Little Gidding as a place where prayer has been valid, and hundreds of visitors and pilgrims come each year to experience the beauty and holiness of this quiet and peaceful place. Karen and I first visited Little Gidding when we moved to the area in 1986 and I’ve been Chair of the Friends of Little Gidding for the last decade. Another of my long-term interests is heraldry, which first drew my attention as a child at the end of the 1960s, and I have belonged to the Heraldry Society since 1974.

These two long-term interests come together in the windows of Little Gidding Church, which display the heraldry of Nicholas Ferrar, King Charles I, John Williams Bishop of Lincoln, and William Hopkinson, the 19th century landlord who restored the church. In an article on the website of the Friends of Little Gidding I describe the four windows and also investigate the coat of arms granted to Nicholas Ferrar’s father, Nicholas senior, and how this differs from the arms depicted in the window.

0 CommentsWhat happens next?

At around 2pm on Tuesday 30 January 1649, following a show trial and conviction, King Charles I was executed. It is said that a great moan “as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again” arose from the crowd assembled in Whitehall, and the event sent shockwaves around the country and across Europe. It was the most disruptive event seen in the country, certainly since Henry Tudor had defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth to bring a final end to the Wars of the Roses. King Charles had not perhaps been a great king, and his record as ruler is not unblemished: his misfortunes at least partly he had brought upon himself by his stubborness, and by his view of his role as king by divine right.

And today, 31 January 2020, we see another disruptive event. At 11pm this country will formally leave the European Union, bringing to an end the legal relationship that began nearly 50 years ago on 1 January 1973. It is an event that over the last few years has divided the country, divided families and friends in a way rarely seen. It would have been hard to predict, even five years ago, what would come to pass, and what a bitter turn our political system and political dialogue would take. But whatever misgivings many of us will feel, the legislation is in place, and the deed will happen later today. For many this is a sad and bitter day: the European project in which we have participated for half a century was forged in the aftermath of the Second World War. It originated in treaties that tied the former warring countries, led by France and Germany, into trade deals that made them more and more dependent on each other, and therefore so much less likely to go to war again. In the previous 100 years, France and Germany had been at war three times, Paris had twice been occupied by Germany, and Alsace-Lorraine had changed country four times. Alsace-Lorraine and its city of Strasbourg were a key coal and steel producing region, and the EU began as a “coal and steel community”. For 60 years or more the EU and its predecessors have played an important part in ensuring that there was not another war in western Europe – whilst the trans-Atlantic NATO alliance helped prevent war with the Soviet Union and its eastern European satellite states. The EU has also played its part in ensuring that our ideals of democracy and equality before the law, of freedom from state oppression and so on have prospered within its member countries. Greece, Portugal and Spain, all formerly under the rule of right-wing or military dictatorships, were the first to benefit from this, their fledgling democracies joining the Community in the 1980s. And after the fall of the Soviet Union the countries of eastern Europe queued up to join the Union, keen for both the economic benefits and the support for democracy and rule of law. These benefits have not come for free. The EU and its predecessors have funded the development of poorer parts of Europe, helping to remove the social problems that led to political problems. That has meant that the richer, more stable countries, such as our own, as well as France and Germany and the richer north-western fringe have seen a net outflow of money, of tax revenue. That is perhaps the price of peace, and is considerably cheaper both financially and in terms of human lives than war would have been. But overall there has been a longer period of peace between these countries than at any time in the past, and a greater and prolonged period of economic prosperity, despite various hiccups along the way.

So what happens next?

We know what happened after the execution of Charles I.

In the immediate aftermath, Parliament, led by Cromwell, refused to allow the proclamation of the Prince of Wales as King Charles II, and instead declared the abolition of the monarchy. A republican form of government, the “Commonwealth”, was put in place, the House of Lords abolished, and bishops removed. The rump of the Long Parliament (which had engineered the king’s trial and execution) continued to sit. That Parliament had been elected in 1640, before the Civil War, though at the end of 1648 the Army, led by Colonel Pride, had expelled those members that did not support the Army. In 1653, Cromwell ejected this Rump Parliament and the country essentially became a kind of military dictatorship, with Oliver Cromwell, the leader of the Army, as the strongman.

In 1659, after Oliver Cromwell had died, there was finally a reaction. The Long Parliament was restored, and it called for a return to monarchy. After a period of negotiation, in May 1660 the eldest son of Charles I returned to England from exile in the Netherlands, and was proclaimed and crowned as King Charles II. The restored monarchy was not quite the same as that which had been abolished in 1649, and Charles II understood the limits within which he ruled. It had taken 11 years from the execution of his father until the Restoration, and many of those years must have been dark and difficult for the exiled prince, and dark and difficult for his supporters back in Britain. But eventually they prevailed, and the republican Commonwealth was consigned to history, a mere footnote in the list of Kings and Queens.

Will something similar happen? Will there be a period in which this country gradually comes to see that it has made an enormous mistake, leading eventually to a reassessment of our position, and finally a significant majority to want to rejoin the European Union? That is my hope and expectation. Maybe it will take a decade or more, just as it took a decade or so for the monarchy to be restored in 1660. It does take time to make such a major change in political direction, and right now we are moving on the opposite course.

But the dark day of 30 January 1649 held the promise of restoration. And this dark day too, 31 January 2020, holds that promise also.

Remember!

2 CommentsThe Structure of Lancashire and Bristol Surprise Major

An earlier post described the structure of Bristol Surprise Major in terms of either treble bobbing with the treble, or plain hunting right and wrong without the treble. Lancashire Surprise Major is built on the same principles, the primary difference being that plain hunting right and wrong are done the other way round. Additionally, in Lancashire a bell makes 2nd place at the lead end, and the bells in 3–4 continue dodging with each other (and at the half lead a bell makes 7th place under the treble, while the bells in 5–6 continue dodging with each other).

We can show the two methods alongside each other, like this:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | b | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||

| Bristol | Lancashire | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | h | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | h | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | b | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | h | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | b | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | h | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 dodges down with treble in 5–6; | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 6 | b | - | - | - | - | 1 | 7 | 8 | 6 | |||||||

| 8 & 6 dodge at the back | - | - | - | - | 7 | 1 | 6 | 8 | h | - | - | - | - | 7 | 1 | 6 | 8 | |||||||

| - | - | - | - | 1 | 7 | 8 | 6 | b | - | - | - | - | 1 | 7 | 8 | 6 | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | 7 | 1 | 6 | 8 | h | - | - | - | - | 7 | 1 | 6 | 8 | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 dodges down with the treble in 7–8; | - | - | - | 7 | 6 | 1 | 8 | b | - | - | - | - | 7 | 6 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 & 6 dodge in 5–6 | - | - | - | - | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | h | - | - | - | - | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | |||||||

| - | - | - | - | 7 | 6 | 1 | 8 | b | - | - | - | - | 7 | 6 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||

| approaching half-lead: bell in 5th place drops down to the front 4; bell in 4th place comes out to the back 4 |

- | - | - | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | h | - | - | - | - | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | |||||||

| hl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 dodges up with the treble in 7–8; | - | - | - | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 1 | b | - | - | - | - | 7 | 6 | 8 | 1 | treble-bobbing bells change direction | ||||||

| 5 & 8 dodge in 5–6 | - | - | - | - | 8 | 5 | 1 | 7 | h | - | - | - | - | 6 | 7 | 1 | 8 | |||||||

| - | - | - | - | 5 | 8 | 7 | 1 | b | - | - | - | - | 7 | 6 | 8 | 1 | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | 8 | 5 | 1 | 7 | h | - | - | - | - | 6 | 7 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 dodges up with the treble in 5–6; | - | - | - | - | 8 | 1 | 5 | 7 | b | - | - | - | - | 6 | 1 | 7 | 8 | |||||||

| 5 & 7 dodge at the back | - | - | - | - | 1 | 8 | 7 | 5 | h | - | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 8 | 7 | |||||||

| - | - | - | - | 8 | 1 | 5 | 7 | b | - | - | - | - | 6 | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||

| - | - | - | 6 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 5 | h | - | - | - | 4 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 7 | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| treble goes down; 6 comes up | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 7 | b | - | - | - | 1 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | treble goes down; 4 comes up | ||||||

| back four bells plain hunt wrong | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | h | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 4 | 8 | 7 | back four bells plain hunt right | ||||||

| (b&h) | - | - | - | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | b | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 7 | (h&b) | ||||||

| - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | h | - | - | 1 | - | 8 | 6 | 7 | 4 | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| back four bells plain hunt right | - | 1 | - | - | 7 | 5 | 8 | 6 | b | - | 1 | - | - | 6 | 8 | 4 | 7 | back four bells plain hunt wrong | ||||||

| (h&b) | 1 | - | - | - | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | h | 1 | - | - | - | 6 | 4 | 8 | 7 | (b&h) | ||||||

| - | 1 | - | - | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | b | - | 1 | - | - | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||

| approaching lead end: bell in 5th place drops down to the front 4; bell in 4th place comes out to the back 4 |

1 | - | - | 3 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | h | 1 | - | - | - | 4 | 7 | 6 | 8 | |||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| lead end | 1 | - | - | 6 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 7 | b | 1 | - | - | - | 7 | 4 | 8 | 6 | |||||||

| le | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| new place bells for this lead | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | new place bells for this lead | |||||||||||||||

| back four bells plain hunt right | - | 1 | - | - | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | h | - | 1 | - | - | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | back four bells plain hunt wrong | ||||||

| (h&b) | 1 | - | - | - | 6 | 8 | 5 | 7 | b | 1 | - | - | - | 7 | 5 | 8 | 6 | (b&h) | ||||||

| - | 1 | - | - | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | h | - | 1 | - | - | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| back four bells plain hunt wrong | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 8 | 5 | 7 | b | - | - | 1 | - | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | back four bells plain hunt right | ||||||

| (b&h) | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | h | - | - | - | 1 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | (h&b) | ||||||

| - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | b | - | - | 1 | - | 7 | 5 | 8 | 6 | ||||||||

| - | - | - | 1 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | h | - | - | - | 1 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | ||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 dodges down with treble in 5–6; | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 6 | b | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 6 | |||||||

| 8 & 6 dodge at the back | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

0 Comments

The Structure of Bristol Surprise Major

Some 18 months ago, I described learning Bristol Surprise Major. I haven’t rung very much of it since then, but I want to look at its structure – what the different bells are doing and how it fits together. Because it’s really very simple, and can be described in a few short sentences:

- The treble always treble bobs, out to the back, and then back down to the front, over and over again.

- The other bells work together, either as a group on the front four, or as a group on the back four, and from time to time a bell moves from the front group to the back group, or vice versa.

So far so good, now for the clever part: - All the bells in the group that contains the treble simply treble-bob inside that group, in phase with the treble, up and down or down and up, until the treble crosses to the other group.

- The four bells in the other group (the one without the treble) just plain hunt; and every time the treble (which is in the other group) moves from one dodging position to another, the four plain-hunting bells switch from hunting “right” (where “leading” and “lying” are made at hand and back) to hunting “wrong” (where “leading” and “lying” are made at back and hand) or vice versa. See below for an explanation of moving from one dodging position to another and of “leading” and “lying”.

- There are three occasions when a bell, other than the treble, passes from one group to the other.

- When the treble itself moves from one group to the other, a bell from the other group must move in the opposite direction;

- When the treble leads or lies, the two bells that are in 4–5 swap places.

And that’s it. Now you understand how Bristol Surprise Major works.

Before moving on, an explanation or clarification of the words moving from one dodging position to another. The treble dodges 1–2 up, and then moves to dodge 3–4 up, and then to dodge 5–6 up. The four strokes when it is in 3–4 are one dodging position, and the four strokes when it is in 5–6 are the next dodging position. The point at which the treble moves from one dodging position to the next is called a cross-section.

At the lead-end and the half-lead, the method is symmetric as the treble leads or lies at the back, and so the plain-hunting bells do not change direction. The treble is considered to be in the same dodging position (1–2) all the time that it is dodging 1–2 down, leading, and dodging 1–2 up at the front, and similarly in the 7–8 dodging position all the time that it is dodging 7–8 up, lying, and dodging 7–8 down at the back. Expressing that slightly differently, at the front and back, the treble spends eight strokes in the same dodging position: eight strokes in 1–2 (when it is dodging 1–2 down, leading, and dodging 1–2 up); and eight strokes in 7–8 (when it is dodging 7–8 up, lying, and dodging 7–8 down). So when the treble is at the front or the back, the bells that are respectively at the back or the front all plain hunt for eight blows before changing direction. We’ll see this more clearly when we trace out the work of each bell.

It’s also worth noting that “leading” and “lying” are in quotation marks, because this term here includes leading and lying within each group of four. So if while plain hunting you are making two blows in fourth place this is included in “lying” because you are lying at the back of your group of four; and similarly if while plain hunting you are making two blows in fifth place this is included in “leading” because you are leading your group of four.

With that introduction, we can look at how the bells interact with each other and with the treble.

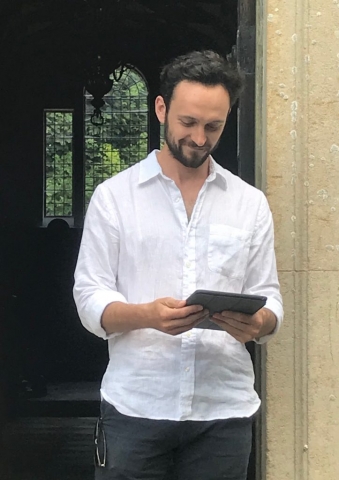

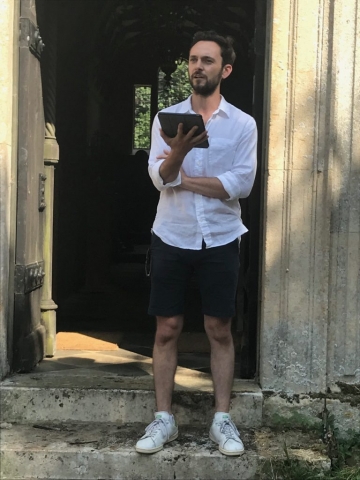

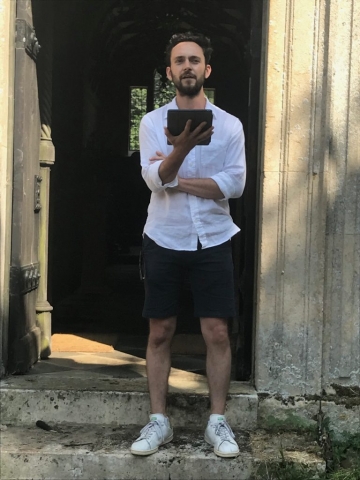

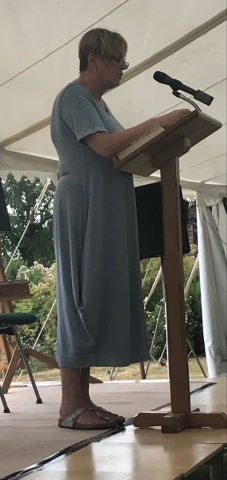

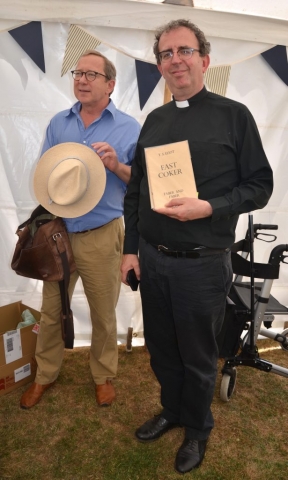

1 CommentT S Eliot Festival 2018

This year’s T S Eliot Festival at Little Gidding was held on Sunday 8 July 2018. Here is a selection of pictures by Carry Akroyd.

0 CommentsCentenary of the WW1 Armistice

Over the last few years the Church of England has published various liturgical resources for commemorating the centenary of significant moments in the First World War.

It has now added to that collection a set of resources for the centenary of the Armistice on 11 November, and entitled ‘Steps towards Reconciliation’: a monologue interspersed with words and music.

How are we to mark the end of a War in which so many lives were lost and damaged? We will certainly remember, but we must also commit ourselves afresh to working together for peace. Reconciliation requires an honest ‘truth telling’, and the text that follows seeks to respect the fact that we may only be able to take steps towards that goal.

This is an imaginative and thoughtful resource that can be used in a number of settings on and around 11 November 2018. It has been compiled by members of the Liturgical Commission.

The text is available as a pdf file here.

1 CommentTowards a Safer Church: Liturgical Resources

On Friday, the Liturgical Commission of the Church of England published “safeguarding resources, for use in churches across the country, including Bible readings, prayers and suggested hymns, chosen in consultation with survivors” under the title Towards a Safer Church: Liturgical Resources.

There is a press release here, and the liturgical resources are available in PDF format here

The Chair of the Liturgical Commission, Robert Atwell, Bishop of Exeter, in an introduction to the resources has written:

The Church needs to be at the vanguard of fostering a change of culture across society. Safeguarding is at the forefront of public consciousness and the Church needs to embody best practice in safeguarding in our network of parishes, schools and chaplaincies as part of our commitment to excellence in pastoral care.

Many of these resources are already being used widely across our churches, but we thought it would be helpful to gather them into one place for ease of access. Collectively they are neither the first word nor the last word on this subject, but they are offered in the hope that by God’s grace the Church may become a safer place where everyone is valued.

Libby Lane, Bishop of Stockport, has also written about the resources here

The resources have been compiled by the Liturgical Commission and staff, in consultation with survivors, who have themselves suggested some of the resources, with the aim providing prayers and other resources for various occasions. This includes use with survivors and others directly affected, as well as events such as the commissioning of safeguarding officers in parishes and dioceses. Most of the material had been previously published (including commended and authorized liturgical texts), but it has been brought together in one place so that it is easier to find and to use.

(This item has also been posted on the main Thinking Anglicans page.)

0 CommentsThinking about Yorkshire and Pudsey Surprise

I looked recently at the underlying structure of Cambridge Surprise on any number of bells (6 or more), and now I want to do the same with Yorkshire and Pudsey Surprise on any number (8 or more, since they are false on 6 bells, though still ringable as Yorkshire/Pudsey Block Delight Minor). This may well not directly help you to ring these methods, especially if you are just learning them. But understanding the structure of a method helps you know why you’re doing what you are doing, and what other bells are doing around you.

You might think Pudsey is a slightly odd choice to include immediately after Cambridge, but there’s a good reason why. In many ways it is the complement of Yorkshire: the changes each of these methods make, compared with Cambridge, are essentially identical except that they are made in different places.

The basic idea of Yorkshire and Pudsey is similar to Cambridge: the treble always treble-bob hunts in each dodging position (1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, etc); and wherever possible the other bells treble-bob hunt, but out of phase with the treble.

(See the article on Cambridge structure for a reminder of what it means to treble-bob hunt either in phase or out of phase with the treble.)

But Yorkshire and Pudsey each make one additional change to Cambridge. In each of them there is one bell that treble-bob hunts in phase with and adjacent to the treble, and the other bells have to deal with that bell as well as with the treble. The two methods differ only in which bell is in phase with the treble, and therefore in which places the extra adjustments must be made.

In Pudsey, it is the 3rd-place bell, which treble-bobs up to the back, dodging down with the treble and making places under the treble at the half-lead, and then dodging up with the treble and back down. Except when dodging with the treble at the back it is always one dodging position higher than the treble.

In Yorkshire, conversely, a bell treble-bobs down to the front, dodges up with the treble and makes 2nds place, and then dodges down with the treble and treble bobs out to the back. This bell treble bobs one dodging position lower than the treble. Whereas in Pudsey the work begins and ends when the treble is at the front, in Yorkshire it begins and ends when the treble is at the back, i.e. from the half-lead to the next half lead, and begins as the work of the 5th-place bell, which becomes the 2nd-place bell at the lead-end in the middle of this piece of work.

| Yorkshire | Pudsey | |||

| half-lead end | -----5-1 |

1-3----- |

lead end | |

----5-1- |

-1-3---- |

|||

-----5-1 |

1-3----- |

|||

----5-1- |

-1-3---- |

|||

| treble-bobs down to the front | ---5-1-- |

--1-3--- |

treble-bobs out to the back | |

--5-1--- |

---1-3-- |

|||

---5-1-- |

--1-3--- |

|||

--5-1--- |

---1-3-- |

|||

-5-1---- |

----1-3- |

|||

5-1----- |

-----1-3 |

|||

-5-1---- |

----1-3- |

|||

5-1----- |

-----1-3 |

|||

51------ |

------13 |

|||

15------ |

------31 |

|||

| where it dodges with the treble | 51------ |

------13 |

where it dodges with the treble | |

15------ |

------31 |

|||

| makes 2nd place over the treble | 12------ |

------31 |

makes (n‑1)th place under the treble | |

21------ |

------13 |

|||

| and dodges down with the treble | 12------ |

------31 |

and dodges up with the treble | |

21------ |

------13 |

|||

2-1----- |

-----1-3 |

|||

| and treble bobs out | -2-1---- |

----1-3- |

and treble bobs down | |

2-1----- |

-----1-3 |

|||

-2-1---- |

----1-3- |

|||

--2-1--- |

---1-3-- |

|||

---2-1-- |

--1-3--- |

|||

--2-1--- |

---1-3-- |

|||

---2-1-- |

--1-3--- |

|||

----2-1- |

-1-3---- |

|||

-----2-1 |

1-3----- |

|||

----2-1- |

-1-3---- |

|||

-----2-1 |

1-3----- |

|||

----2--1 |

1--3---- |

These two pieces of work are mirror images of each other.

Next, let’s consider one small but important point. In Yorkshire, the bell treble-bobbing in phase with the treble is below the treble. The other bells must change their behaviour (compared with Cambridge) whenever they meet this bell, and by definition that can only happen below the treble, since that’s where this in-phase treble bobbing happens. Whenever a bell is above the treble it behaves in exactly the same fashion as it would in Cambridge. That’s why Yorkshire is “Cambridge above the treble”.

In Pudsey, on the other hand, the bell treble-bobbing in-phase with the treble is above the treble. The other bells must adjust their behaviour when they meet this bell above the treble, so the changes from Cambridge occur above the treble, but below the treble Pudsey is the same as Cambridge.

Now let’s turn to the other bells. They are trying to treble-bob out of phase, so when they encounter these two bells (the treble and the bell in-phase with the treble) then they must adapt their work.

Because the two bells are in adjacent positions, we will dodge with one and plain hunt past the other, though which of these comes first depends on where we meet them. And in addition, we must also make places adjacent to the dodge to switch phase.

There are two possibilities.

We can either plain hunt past a bell, dodge with the other, and then make places and (now back out of phase) dodge again. Or else we do the opposite of this: after dodging out of phase, we make places to get in phase, dodge with one of the in-phase bells and then plain hunt past the other.

Which we do depends on whether we have already dodged when we meet the first of the two bells.

If we meet the first of the two bells after we have dodged, then they have not yet dodged, so we must make places to wait for them, dodge, and then pass through the next dodging position to get back out of phase, and then resume out-of-phase treble bobbing. (In the following diagrams the treble and the in-phase bell are labelled p and q; in Pudsey p is the treble and q the in-phase bell; in Yorkshire p is the in-phase bell and q is the treble.)

| when going down to the front |

when going out to the back |

||

p-q--x-- |

--x--p-q |

||

-p-qx--- |

---xp-q- |

||

p-q-x--- |

---x-p-q |

||

-p-q-x-- |

--x-p-q- |

||

--p-qx-- |

--xp-q-- |

||

---pxq-- |

--pxq--- |

||

--p-qx-- |

--xp-q-- |

||

---pxq-- |

--pxq--- |

||

---xp-q- |

-p-qx--- |

||

--x--p-q |

p-q--x-- |

||

-x--p-q- |

-p-q--x- |

||

x----p-q |

p-q----x |

||

-x----pq |

pq----x- |

||

x-----qp |

qp-----x |

||

| Alternatively, if we meet the two bells before we have dodged, then they have already dodged and one of them is about to come into our current position so we must miss a dodge and go straight on to dodge with the other one, and having done so, make places to get back out of phase and resume out-of-phase treble-bobbing: | |||

p-q--x-- |

--x--p-q |

||

-p-qx--- |

---xp-q- |

||

--pxq--- |

---pxq-- |

||

--xp-q-- |

--p-qx-- |

||

--pxq--- |

---pxq-- |

||

--xp-q-- |

--p-qx-- |

||

--x-p-q- |

-p-q-x-- |

||

---x-p-q |

p-q-x--- |

||

---xp-q- |

-p-qx--- |

||

--x--p-q |

p-q--x-- |

||

---x--pq |

pq--x--- |

||

--x---qp |

qp---x-- |

||

There’s one more detail before we have enough information to understand each of these methods. If we are about to meet the treble or in-phase bell at the back, when we are in the topmost dodging position, then rather than missing a dodge or making places to get in phase we add an extra dodge. We’ve already seen this in Cambridge when we were about to meet the treble and we were at the back. Yorkshire here is identical to Cambridge (because we are above the treble), but in Pudsey this also applies when meeting the in-phase bell, so we must do these double dodges when about to meet that bell. And because the method is symmetrical, when we said “about to meet”, the same applies when “reaching the back having just met”, as it does in Cambridge.

In the full article, we’ll look at the details of Yorkshire, then at Pudsey, and then do a final comparison of the two methods.

0 CommentsThinking about Yorkshire Surprise

I looked recently at the underlying structure of Cambridge Surprise on any number of bells (6 or more), and now I want to do the same with Yorkshire Surprise on any number (8 or more, since it is false on 6 bells).

The basic idea of Yorkshire is similar to Cambridge: the treble always treble-bob hunts in each dodging position (1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, etc), and wherever possible the other bells treble-bob hunt, but out of phase with the treble.

(See the article on Cambridge structure for a reminder of what it means to treble-bob hunt either in phase or out of phase with the treble.)

In Yorkshire there is an exception to this out-of-phase treble bobbing: starting when the treble is dodging at the back, one of the bells treble-bobs in phase with the treble and one dodging position below it, making 2nd place over the treble at the lead-end, and continuing in phase until the treble reaches the back again.

Everything else in Yorkshire is a consequence of this change from Cambridge.

The bell that starts doing this in-phase treble bobbing is the 5th-place bell, from the half-lead when it has passed the treble at the back, and continuing as the 2nd-place bell until the half-lead as it approaches the back. For brevity, I call this piece of work the in-phase bell, because it is treble-bob hunting in phase with the treble. (This isn’t a shorthand I have come across elsewhere, but it is a convenient term.)

Because the treble and the in-phase bell are in adjacent dodging positions, the other bells meet the in-phase bell immediately before or immediately after meeting the treble, They must either pass it or dodge with it, just as they do with the treble.

Remember that in Cambridge places a bell dodges with the treble in the middle of the work, making places either side of that dodge in order first to get in phase with the treble, and then to get back out of phase. But in Yorkshire there is immediately another in-phase bell to deal with: so if we have dodged with the treble we must curtail Cambridge places to pass the in-phase bell. Or alternatively, if it’s the treble that is passed, then we must dodge with the in-phase bell and make places to change phase. This changes Cambridge places into Yorkshire places and also adds them in positions where in Cambridge you just plain hunt past the treble.

Let’s see what that means in practice.

0 CommentsLooking at Cambridge Surprise (again)

I’ve been ringing Cambridge Surprise for quite a few years now. I began with Minor (in 2005), learning the various pieces of work by rote. Then when I could do that I moved on to Major (in 2006), again, learning by rote the bits that were different from Minor. Then I got to the point that I could barely remember how to ring Minor, because I always forgot which bits of Major to leave out. I’ve got over that too, and recently have begun to ring Minor a bit more, because we have ringers who have moved on to learning it.

All of which sparked an interest in learning Cambridge Surprise Royal, i.e. on 10 bells. (Ringing it would be a rather different matter as I’m not a ten-bell ringer, and although I have rung Caters a handful of times, I’ve never rung Royal. But I want to stick with the theory for a bit.)

So I looked up the blue line for Cambridge Surprise Royal, and in searching for it I came instead across descriptions of Cambridge, and I realized I had been missing something about Cambridge all these years. The sort of thing that makes me wonder whether I could have learnt the method in a much better way — rather than learning sections by rote, and then re-learning it by place bells, instead learning it and ringing it from first principles. Because the principle behind Cambridge, on any number of bells, is quite simple.

Here it is:

- the treble always treble-bob hunts from the front, out to the back where it lies behind and then treble-bob hunts down to the front again; and it does this over and over again, (n‑1) times in a plain course, where n is the number of bells (6 for Minor, 8 for Major, 10 for Royal, etc).

- each of the other bells also treble-bob hunts, but it does so “out of phase” with the treble. This means that whenever it meets the treble, it must change its pattern of treble-bob hunting to fit around the treble.

What do we mean by treble-bob hunting “out of phase”, and what are the consequences of this?

1 Comment