Counting Sixes in Steadman

Steadman Triples has long been one of my favourite methods to ring. I have previously looked at how the method is constructed of sets of six blows, and how to keep track of “quick” and “slow” sixes. I’ve also learnt to call simple touches of Triples, with calls labelled “Q” and “S”. But more complicated touches use a different notation: the blocks of six blows that make up the method are consecutively numbered, and the sixes in which bobs and singles are called are noted. Alternatively the count is of possible calling positions, since a bob or single may potentially be called at the fifth blow of any six, and the caller needs to know which of these positions to actually call.

The challenge then becomes one of counting sixes – with 100% accuracy. Whilst simultaneously counting your place and keeping track of quick and slow sixes. For me this is brain overload, and I cannot accurately keep all this information in my head. The main problem is that I am trying to keep track of two numbers: my place, and the number of the six. And in the first seven sixes these numbers will be in the same range of 1 to 7, so there is an extra risk of confusing which is which, or incrementing the wrong one, and so on.

What then to do? The first thing is – for the moment – to let other people call touches, while I get my head around the counting. And the breakthrough in being able to count sixes has been the realization that I don’t actually need to count my place: I can pretty much ring Steadman by rhythm and by knowing its structure.

First, then, the rhythm. Dee-dah, dee-dah, dee-dah. That’s the six blows that make up the Steadman unit: handstroke, backstroke, handstroke, backstroke, handstroke, backstroke. Dee-dah, dee-dah, dee-dah. So, if you are double-dodging 4–5 up, that would be (4th, 5th), (4th, 5th), (4th, 5th). If you have just gone down to the front three as a slow bell then it’s (3rd, 3rd), (2nd, lead), (lead, 2nd). In each case I have bracketted the handstroke-backstroke pairs, each of which is a dee-dah.

And then the structure. Steadman work is divided inro two parts. Above third place you double dodge out to the back and then back down again, and into the front three. Each double dodge is one six. If you are on the front then you plain hunt for six blows, then change direction and hunt for the next six blows and so on. If you are in 3rd place at the end of a six then you go out to 4th place and start double-dodging. And you have to know whether to start the front work by plain hunting right (a quick six) or wrong (a slow six) – I’ll come to that in a moment. In the back of my mnd while ringing on the front is the superimposed structure of the slow work – the whole turns and half turns – and these reinforce what I am ringing, but at any given point it’s just plain hunting on three, changing direction after six blows. And the six blows felt rather than counted. Plain hunting on three is sufficiently simple that it can be done without counting my place.

On top of this ringing I am trying to count the sixes. At each handstroke, more or less, I think “this is number n”, or just “this is n”, deliberately saying it to myself in a way that I am less likely to confuse with my place. Steadman begins part way through a six, so the first two blows, right at the start, handstroke and backstroke, are the last two blows of the first six, and sixes continue after that. A plain course of Steadman Triples will come round four blows into the 15th six, while a touch with two Q and two S bobs is twice as long, coming round at the fourth blow of the 29th six.

As for keeping track of quick and slow sixes, that is implicit in the count. A six with an odd number (1, 3, 5, 7 …) is quick, and a six with an even number (2, 4, 6, 8 …) is slow. It just needs a tiny bit of extra brainpower to work this out on the fly.

0 CommentsHarvest Thanksgiving: 6 October 2024

Readings: Joel 2.21–27; Psalm 126; 1 Timothy 6.6–10; Matthew 6.25–33

May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart

be acceptable in your sight, O Lord.

Harvest Festival.

Do you remember celebrating Harvest Festival as a child?

I can recall as a young schoolboy what a big occasion it was.

We’d line up in class,

and then our crocodiles would march down to the village church,

half a mile away,

each clutching a bag of apples or tin of baked beans

or something else that our mothers had given us to take.

We’d sing one or two harvest hymns

and deposit our produce.

The rector would say a few words and some prayers,

and then we’d traipse back to school.

It’s a memory of quite a long time ago,

over half a century for me,

and obviously made a bit of an impression on the young Simon.

But what I can say is that

I didn’t really make much of a connection with real life.

I mean, “Fair waved the golden corn”

didn’t seem to have very much to do

with buying food from the butcher

or the greengrocer or fishmonger –

let alone from the supermarkets

that were just beginning to appear in our town.

Not until I was a good deal older did I begin to understand.

And there’s a clue to help us understand

on the front of today’s service booklet.

You see, the Church actually calls this

not “Harvest Festival” but “Harvest Thanksgiving”.

Not “Harvest Festival” but “Harvest Thanksgiving”.

What’s in a word, you might ask?

Well, quite a lot perhaps.

You see, rather than celebrating

our own cleverness and skill

and the things that we’ve made at a festival,

what we are doing is giving thanks:

giving thanks for the good things that enable us to have …

(well) life.

At harvest that’s particularly thanks that we have food –

enough food for the coming year so we will not starve.

And thanks that for us

that’s actually a pretty remote possibility

– at least I hope it’s pretty remote –

but coupled with concern

that for many around the world

(and indeed in our own country)

not-enough-food is a very real prospect.

And that’s where I think our readings this morning are taking us.

In the Old Testament, Joel reminds his hearers

that God provided for the animals of the field

and for the trees bearing fruit.

And similarly for his people God will provide plenty.

And Jesus in the gospel reading

makes a similar point, doesn’t he?

That God provides for the birds of the air

and for the flowers of the field.

And, Jesus says, in God’s kingdom we too will be provided for.

Jesus tells his hearers

‘Do not worry, saying, “What will we eat?”

or “What will we drink?”

or “What will we wear?” ’

Instead, Jesus’s instruction, as we heard this morning. is this:

‘Strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness,

and all these things will be given to you as well.’

How does that work, do you think?

How will we be provided for?

I think it comes back to thankfulness

and to remembering how the kingdom of God works.

So here’s a little exercise for us all …

You’ll remember that in the gospels

Jesus tells us that the kingdom of God is near, it’s at hand.

I want us to think a little about that.

When, I wonder, do you think

we come closest to living in God’s kingdom?

Do you ever think about that?

Let’s just take a few moments to consider it now:

When do you think we come closest to living in God’s kingdom?

You might want to think about this on your own,

or you might want to turn to the person next to you

and share ideas.

When do you think we come closest

to living in the kingdom of God?

… [[pause for a few brief moments, perhaps 10 seconds;

if people start talking to each other give them a bit longer]]

Okay, how did you do?

Now you can find out

whether your thoughts are anything like mine!

Because I reckon there’s actually quite a simple answer –

though I’m not saying it’s necessarily easy to put into practice!

In the gospels Jesus tells us

that we approach being in God’s kingdom …

whenever we do God’s will –

when we do God’s will here on earth as it is done in heaven

And that means sharing the things that God has given us:

sharing our food,

sharing our wealth,

sharing our skills and our knowledge,

sharing our time and our energy.

And sharing God’s peace.

Of the good things that God has given us

we give back the first fruits.

As God is generous to us,

so we have the opportunity

to be generous with all that we have.

In God’s kingdom, you see,

everyone benefits from generosity –

from God’s generosity to all creation …

and from our generosity to one another.

Jesus calls us to consider what we can give –

what we can give back to God,

and what we can give to one another.

So, as we give thanks today at harvest,

we do well to remember

that God calls us to share

the goodness, the bounty,

that we have been given.

That’s not just good food,

but also things like peace and security,

housing and personal dignity.

This year in St Ives,

Father Mark and Callum have been helping

some of our local schools and other organizations

give thanks at harvest

and to bring gifts that will go to the St Ives foodbank.

For their generosity we can be very grateful.

And we too:

as we bring our gifts

and lay them before God at the altar,

as we give our time and our talents and our wealth,

we are sharing God’s love

with some of those in our community

who desperately need it.

And as we love our neighbours who are in need,

as we are generous to them,

so too we are loving Jesus.

Because – make no mistake –

It is when we serve the least of these

our brothers and sisters …

it is then that we serve Jesus.

It is then that we come near to the kingdom of God.

Thanks be to God.

0 CommentsChurch Clocks

Trinity 7: 14 July 2024

Readings: 2 Samuel 6.1–5, 12b-19; Psalm 24; Ephesians 1.3–14; Mark 6.14–29

May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in your sight, O Lord.

(The east windows at St John the Baptist Church, Leamington Spa; photo by Aidan McRae Thomson)

When I came to prepare this sermon, two themes stood out.

First, John the Baptist and my “relationship” with him.

I’ll come back to that in a moment.

The other theme from our readings is …

Well … it’s dancing!

David dancing before the Ark;

Salome dancing before Herod.

Now it’s a bit of a co-incidence

that they are paired here together:

we’ve been hearing the story of David

over the last few weeks,

and we just happen to arrive at this episode

as the gospel gets to this interlude in Jesus’s ministry.

But I expect lots of you watch tv programmes about dancing –

Strictly Come Dancing anyone?

So perhaps you’re imagining David and Salome

as celebrity contestants in Strictly.

There’s David, king of Israel,

stripped down to a “linen ephod”

whatever that is,

but it definitely sounds a bit scanty doesn’t it?

Dancing, ooh, the quickstep, perhaps.

And the princess from Galilee, Salome,

(though she is called Herodias

in our bible translation this morning) –

young and attractive,

dancing something a bit raunchy, a tango, maybe.

In popular modern culture

it’s the dance of the seven veils,

though that was only invented by the writer Oscar Wilde –

the biblical text lacks the eroticism

which we might imagine into the story.

As for David,

the ephod that he wore was a priestly garment –

knee-length, open at the sides, belted at the waist –

perhaps a bit like the vestment

that a deacon sometimes wears, a dalmatic.

But back to John the Baptist.

I have, as I mentioned, a bit of a history with John.

It’s getting on for 40 years since Karen and I moved here –

and when not serving, I’ve usually sat somewhere over there:

right by Comper’s statue of John the Baptist.

But long before that,

from when I was born,

I went to a church dedicated to John the Baptist:

I was a choirboy and then a server,

and I was formed as a young Christian.

Now that church was a great Victorian barn of a place,

bigger than here.

And one feature I remember vividly

was a set of three big windows at the east end,

behind and above the altar.

In the lower part of each window

there’s a scene from the story of John the Baptist,

and above each of them a parallel scene

from the story of Jesus.

So the left window depicts the Nativity of Jesus,

a manger with a shepherd and worshipping angels,

while below are scenes from Luke’s account of John’s birth.

And the bottom of the centre window

shows the story we have heard today.

There is Salome dancing –

fully and demurely robed I hasten to add.

There is John

kneeling before the executioner wielding his sword.

There is a man opening a door,

presumably bringing in the head of John,

though that horror isn’t shown.

So, why do the windows pair these scenes?

Well John was an important figure to the gospel writers,

and all four of them include him in their stories.

He’d been the major figure in what we might call

a religious revival,

and crowds had flocked to see him,

a bit like some Billy Graham rally perhaps.

Among them came Jesus.

Are the gospel writers a little embarrassed about this?

About Jesus being baptized by John?

About Jesus perhaps playing second fiddle to John?

They want us to understand

that from their point of view,

from our point of view,

John was preparing the way for Jesus.

The first readers and hearers of Mark’s account

must have included people

who had been followers of John,

who perhaps had come out to the Jordan and been baptized,

but maybe had had little involvement with Jesus.

The gospel writer wants these people to see

that Jesus is continuing John’s proclamation:

repentance and new life.

But Jesus brings a new twist to the proclamation.

John had preached repentance

as preparation for the arrival of God’s kingdom.

But Jesus proclaims that God’s kingdom has arrived already,

here, now:

Jesus’s followers – you and me –

can repent

and move from the ways of this world

and live instead in the kingdom of God,

where the hungry and poor,

the troubled and the dispossessed

are lifted up

and people are reconciled

with each other and with God.

And there’s a second message from today’s gospel.

Following Jesus isn’t always easy.

It can be hard to lift up the lowly

and be reconciled with others,

and sometimes others don’t want to be reconciled,

sometimes people don’t want the lowly lifted up,

perhaps because they like to have people to lord it over

or to exploit.

Sometimes there are hard consequences.

Certainly there are hard consequences for John –

that’s the story we have heard today:

John is condemned and executed by Herod.

And soon Jesus in his turn

will be condemned and executed

on the orders of Pontius Pilate

and with the connivance of this same Herod –

and of others who are challenged

by the idea of God’s rule, God’s kingdom.

In death, as in life,

John is the forerunner of Jesus.

And this is what can be seen

in the middle window at my old church:

above the panel with the beheading of John,

we see the Crucifixion.

Jesus pays the ultimate price of love and reconciliation,

put to death by the Roman governor

on charges brought by the Temple leadership,

a conspiracy between the rulers of this world

to attempt to defeat … love.

And there’s one more window to look at.

The third window at my childhood church

reminds us of one more thing.

It shows, in the bottom, the end of today’s story:

John’s disciples come and carry away his body

and place it in a tomb.

It is the end for John.

But the upper section of the window

shows a very different scene.

The follow-up to the death of Jesus

is the empty tomb,

the bursting from the grave,

the defeat of death.

The triumph of hope.

That is to go beyond the story we have heard today, with the message of Jesus:

Love conquers all.

You see,

John had proclaimed

that the end of the world was coming,

and people needed to repent.

And John had been killed and buried.

Jesus, though, proclaims something new:

not the end of the world,

but the end of the age,

and a new age

where God’s will is done on earth as it is in heaven.

And Jesus too is killed and buried … and …

rises to new life.

And that’s what we see in the last of the windows,

that similarity-and-difference between John and Jesus.

John buried; Jesus resurrected –

resurrected to new life,

life in the new age where God’s will is done.

As we heard Paul remind us in his letter to the Ephesians –

Jesus’s death on the Cross

reconciles us to God and also to one another.

And Jesus’s resurrection brings us

to share in life in God’s kingdom.

Right here and now.

So,

unlike John, we are Jesus’s followers.

But, like John,

our role does include preparing the way for Jesus:

preparing the way for Jesus

in the hearts and lives of those around us.

John’s life – and John’s death –

remind us that this might not be easy

but the example he sets

is one of boldness in telling the truth

and in proclaiming the gospel,

the good news that, in Jesus,

the kingdom of God is among us.

Let us each consider this week

how we might begin

to prepare the way to Jesus

for just one person.

Amen.

0 CommentsEaster 2: 7 April 2024

Readings: Acts 4.32–35; Psalm 133; 1 John 1.1 – 2.2; John 20.19–31

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

Football – are you a football fan?

I know some of you are, even if you do support odd teams.

And perhaps, like me,

you sit and watch Match of the Day every Saturday night.

There was a game on the programme a week ago,

and the highlights of the first half were very brief –

almost nothing to show.

But the second half was very different:

full of action as the two teams

(Sheffield United and Fulham)

shared six goals in a thrilling 3‑all draw.

It had been, the commentators and pundits noted,

a real game of two halves.

“A game of two halves” is something of a football cliché –

and it’s also a good summary of our gospel reading this morning.

We heard how, in the first half,

Jesus appeared to the disciples,

on the evening of the first Easter Day.

But Thomas wasn’t there,

and he didn’t believe the others when they told him;

no, he wanted to see for himself.

And Thomas wasn’t afraid of expressing his doubts.

Their teacher dead and buried – and now alive again?

“Well, I’ll believe that when I see it!”

And you know what?

I reckon that’d be the reaction of most of us.

And a week later we get the second half:

Jesus appears again and says,

“Here I am; you didn’t believe it was me;

well look, here are my wounds;

go on, touch them.”

And you may have noticed that the gospel doesn’t say

that Thomas did touch Jesus

or put his hand in the spear-wound on Jesus’s side.

No!

When he sees that Jesus is present

Thomas’s doubt is overcome

and he immediately exclaims

“My Lord – my God!”

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

Here are our two halves:

in the first half Thomas doubts Jesus;

and in the second half Thomas recognizes Jesus.

So, first, Thomas doubts Jesus.

I don’t know about you,

but I find that believing in Jesus still leaves room for doubt.

Having doubts doesn’t mean that faith is lacking.

Doubt is a natural aspect of our faith.

It is natural to question,

to think,

to wrestle with uncertainties,

and to seek understanding.

Doubt can deepen our faith rather than weaken it.

That’s because doubt isn’t the opposite of faith:

doubt is the companion of faith,

the other side of the same coin.

My faith in Jesus isn’t about certainty;

it’s about trust.

Faith in Jesus,

belief in Jesus,

means that we place our trust in him.

That’s the promise that was made at our baptism –

“do you believe and trust in God,

Father, Son and Holy Spirit?”

And trust is about having confidence in someone,

placing our reliance on them,

knowing that they will always be there,

there to help us.

Ultimately, Thomas did place his trust in Jesus.

And when we believe and trust in Jesus

we too know we can rely on him,

even when we doubt.

And we can know that what Jesus says is trustworthy.

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

And after the doubt, what does Thomas do?

He recognizes Jesus.

Recognizing people is one of the fundamental things

that we do as human beings.

Thomas recognized Jesus,

and we too have the opportunity to recognize Jesus,

to recognize the presence of Jesus.

And although there are a number of such occasions,

I want to suggest just a couple of times and places

when we can particularly recognize that Jesus is with us.

So one place we might find Jesus

is when we read the bible,

and especially when we read the four gospels that tell Jesus’s story.

When we tell the story of Jesus,

when we tell the stories about Jesus,

when we tell the stories that Jesus told –

then somehow Jesus is present with us in the telling.

And foremost among those occasions

is when we gather on a Sunday morning

and hear some of that story read,

some of that story proclaimed.

It’s a bit of the service we mark with special solemnity:

we stand (if we are able),

we sing “Alleluia” as an acclamation,

we carry the gospel book in procession

and turn to face the reader,

we burn incense and solemnly cense the book,

and we make a sign of the cross.

The book is lifted high for everyone to see.

All these little signs point to the importance of this moment –

that as we hear the story of Jesus,

the story Jesus told,

then still Jesus is alive here among us,

as he was when his first hearers,

people like Thomas,

gathered around him on the hillside,

or beside the lake,

in the market place,

or at dinner,

and he spoke to them.

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

And another opportunity for us to recognize the presence of Jesus

is also here in this service.

We recognize the presence of Jesus

as we break bread together.

Now “breaking bread” is a turn of phrase,

an idiom.

It’s not just about literally breaking bread,

it’s the whole action of sharing a meal together.

And that’s what we are doing here.

Yes, okay, it’s become a symbolic meal –

a small piece of bread and a sip of wine –

but it is a meal that we share together,

a meal that we share because Jesus himself told us to.

And told us to remember him as we share it.

And as we share that meal,

as we break bread together

and remember that Jesus died for us,

then we recognize that Jesus is here among us –

just as he was with Thomas and the other disciples

when he broke bread and shared supper with them.

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

And Jesus tells us

that when we minister to those in need,

we are ministering to him:

- The homeless, the hungry, the destitute

- The refugee, the foreigner in our midst

- The abused or oppressed

- The sick, the lonely, the depressed,

those suffering from mental illness - People we don’t like, people we’re suspicious of

- And … I’m sure you can think of others to add to this list.

And, you know, Jesus didn’t worry

whether someone had paid their Temple taxes or not;

he didn’t worry whether they were a woman or a man;

a slave or a slave-owner;

a faithful Jew or a Samaritan,

or even a centurion in the occupying army.

Jesus bluntly tells us

that when we share God’s love

by ministering to someone in need

then we are ministering to him.

Here too we will find Jesus.

So I want to leave you with this thought for the week:

who will you recognize Jesus in?

Who will you minister to?

And who will you allow to minister to you?

Like Thomas,

may our encounters with the risen Christ

transform us,

transform those around us,

and transform the world.

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

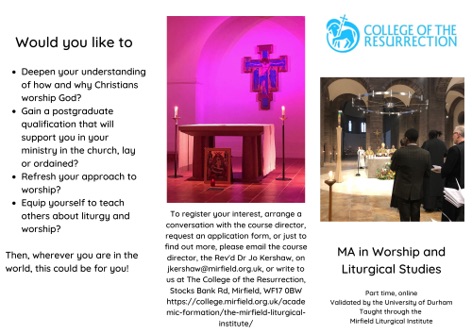

0 CommentsMA in Worship and Liturgical Studies at Mirfield

The Mirfield Liturgical Intitute has recently announced a PGDip / MA in Worship and Liturgical tudies. The qualification is validated by the University of Durham, and can be studied part-time online. The publicity says:

Would you like to

- Deepen your understanding of how and why Christians worship God?

- Gain a postgraduate qualification that will support you in your ministry in the church, lay or ordained?

- Refresh your approach to worship?

- Equip yourself to teach others about liturgy and worship?

To find out more, contact the course director, the Revd Dr Jo Kershaw jkershaw@mirfield.org.uk or at https://college.mirfield.org.uk/academic-formation/the-mirfield-liturgical-institute/

Disclaimer: I should point out that Jo Kershaw and I are not related at all, and our families even come from opposite sides of the Pennines (though Mirfield is on the right side).

0 CommentsAdvent 4: 24 December 2023

Readings: 2 Samuel 7.1–11, 16; Canticle: Magnificat (Luke 1.46–55); Romans 16.25–27; Luke 1.26–38

“The angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth.”

In the name of …

Prequels.

Do you enjoy prequels?

Did you watch Endeavour as a prequel to Morse?

Or perhaps The Phantom Menace and others as prequels to Star Wars?

And what about books?

As a teenager

I worked my way avidly through CS Forester’s Hornblower novels,

reading them in story order,

and finding that all the earlier books were written after the later ones.

The conclusion of the story was already pre-determined –

Hornblower’s failure to achieve this or that;

the death of … spoilers.

Much of this was fixed by throw-away lines in the later books that were already in print.

And today’s gospel reading is a sort of prequel as well.

What’s it a prequel to?

Well, we heard a couple of weeks ago

the start of the gospel according to Mark.

(Mark the evangelist, that is, not Mark the vicar.)

Mark’s account is very widely regarded as the first gospel to have been written,

and so there was a time,

a short time perhaps,

when it was the only gospel in existence.

Perhaps you can remember from two weeks ago how it starts:

The beginning of the gospel [or: good news] of Jesus Christ, the Son of God[1]

and then it describes that beginning:

the preaching of John the Baptist,

and how Jesus arrives on the banks of the Jordan and is baptized by John.

So,

what was Jesus doing before the start of Mark’s account?

I think that’s a natural question to ask.

And in the culture of that time

it might not have been obvious

that he had been born,

or that he had grown from a baby to an adult man.

That’s a somewhat bizarre thing to say, isn’t it? What do I mean?

Well,

ancient mythology is full of stories that skip all that stuff.

Just one example

from the Roman poet Ovid,

who lived just a year or two ahead of Jesus and Luke.

His long verse collection Metamorphoses includes such a tale –

how the immortal gods

Jupiter and Mercury

decided one day to pay a visit in disguise to the mortal world.

They are spurned by everyone

until they meet an impoverished elderly couple,

Philemon and Baucis,

who invite them in and cook them supper

from their own meagre resources,

and gradually realize,

when the goblets of wine never empty,

that their guests are divine.[2]

Now if you think this is far-fetched,

then have a look at the Acts of the Apostles, at chapter 14,

where in an echo of Ovid’s tale, Luke tells us that

Paul and Barnabas are themselves mistaken for exactly the same two gods.[3]

So you can see perhaps

how the sudden appearance of Jesus in the earliest gospel account

as an adult acclaimed as God,

might also be open to misinterpretation.

That Jesus wasn’t really human,

but was a god in disguise.

Perhaps Luke was aware of speculation

about the origin of Jesus and his early life,

but whatever the reason,

he gives us two whole chapters about Jesus

before getting to John baptizing in the River Jordan

(where Mark had begun, remember?).

And here we are:

in the story it’s nine months before the birth of Jesus,

and Luke introduces us to Mary.

We don’t learn much about her though:

that she lives in Nazareth,

and is engaged to be married;

and via the angel that she is favoured by God,

and is related to Elizabeth,

who is herself expecting a child –

that’s the boy who in adulthood will become John the Baptist.

That’s pretty much all the story says about her.

And that’s because the story isn’t really about Mary.

It’s about Jesus.

The things that Mary says and does point us to Jesus.

The angel tells Mary she will have a son,

and that the Holy Spirit will overshadow her,

so that the child will be holy

and called “Son of God”.

Mary, then, will be the bearer of God the Son,

and we can see our Old Testament reading as a parallel to this.

King David wants to build a permanent home for the ark of the Covenant,

the holiest possession of the ancient Israelite people,

and regarded by them as the place where God dwelled.

But the prophet Nathan tells David

that it is not for him to build such a place,

that will come later;

but God will instead establish David’s line for ever.

Two prophecies for the price of one!

First, because Luke traces Jesus’s own ancestry back to King David –

seeing Jesus as fulfilling Nathan’s statement

that David’s line will reign for ever.

And secondly because

we have just heard how Mary will be the bearer of God –

it is her womb that will house God: God the Son.

So what does Mary do?

In the verses immediately after our gospel reading

she legs it,

and seeks out her relative Elizabeth.

And it is while she is with Elizabeth

that, Luke tells us, she praises God.

And earlier in our service today,

we sang a version of the words Luke records:

“With Mary let my soul rejoice”.

(You might like to have the words in front of you now.)

This song, the Magnificat, is not just a song of praise.

It’s also

a trailer or teaser for the story of Jesus,

for the story of Jesus’s mission and teaching,

the story of Jesus’s proclamation of God’s kingdom,

God’s rule.

Because in the Magnificat we can see parallels with Jesus’s later teaching:

- In the synagogue at Nazareth, for example, Jesus identifies himself:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me;

he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor,

release to the captives,

recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free.”[4] - And in another place he teaches:

“Blessed are you who are poor, [or] hungry, [or] who weep.

But woe to you who are rich, you who are full,

for you will be hungry.”[5]

These are the themes we have seen and sung in Mary’s Song,

and they are the themes that continue throughout Jesus’s ministry:

lifting up the hungry and poor,

exalting the humble and meek –

sending the rich away empty.

And in today’s gospel reading

we see them announced at the very start,

at the very moment that Jesus’s conception is first revealed.

Even as Jesus is conceived

Luke tells us that this message is proclaimed.

So is Luke’s account a good prequel?

Well, it’s the prequel that

to much of society

is almost the only bit of the story they remember.

In that sense, yes, it’s a really good prequel.

And yet …

The world around us

is drawing to the end

of its annual orgy of extravagant spending and extravagant consumption,

whilst all about we see:

poverty,

misery,

hatred,

war.

And though we shouldn’t begrudge people a bit of light and fun

and – above all – hope

in the midst of such difficulty,

nonetheless

our job,

our mission,

yours and mine,

is to make sure

that the rest of Jesus’s story is remembered too –

the proclamation of the good news that is the Kingdom of God,

where the poor and the hungry,

the homeless and the refugee,

the war-ravaged –

all who suffer, the downtrodden of society –

are raised up and satisfied,

and enemies are reconciled to each other.

And – our response should be to make that happen,

now, at Christmas time, yes – and also all year round.

Because all that is foreshadowed

in the news that we like Mary, heard today.

The good news

that the baby whose birth we are about to celebrate

saves us

and teaches us how to move

from lives governed by the prince of this world

to lives governed by the prince of peace.

Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.

[1] Mk 1.1 (NRSVAE)

[2] Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book VIII

[3] Acts 14.11, 12

[4] Lk 4.18,19 (NRSVAE)

[5] Lk 6.20–25 (NRSVAE), abbreviated

0 CommentsThe Transfiguration: 6 August 2023

Readings: Daniel 7.9,10,13,14; Psalm 97; 2 Peter 1.16–19; Luke 9.28–36

I don’t know about you, but I’m not much of a film-buff and I don’t often go to the cinema,

perhaps only once, maybe twice, a year, if that.

But I went to the cinema last weekend.

So, there are two big films on right now,

one that I’ll just gloss over as mostly pink

and another that I can say is somewhat grey.

Now I expect my three-year old granddaughter

would love to watch the pink one,

but it was the somewhat-grey film that Karen and I went to see.

It’s a story – a true story – set during the Second World War,

with a bunch of scientists racing to work out how to build a new weapon.

And not just any new weapon, but a new kind of weapon,

a weapon that will unleash untold power.

And just as they’re about to explode the very first test at Los Alamos

– a moment of high drama –

the hero, Robert Oppenheimer, remembers an earlier conversation

(in the film it’s) with a chap called Albert Einstein,

a conversation about an important question –

what’s the worst that might happen in the test?

Well, comes the reply, it could set off a chain reaction,

a chain reaction that might ignite the whole atmosphere,

a chain reaction that might consume and destroy all the earth.

They don’t think that’s very likely, but it is possible.

(And I think you’ll agree that is rather a big downside to any decision.)

So of course they proceed with the test.

There’s a small starting explosion,

and then a great shining, blinding, white light

and then a massive fireball

as the chain reaction in a small lump of uranium causes an explosion of unparalleled ferocity

and then

a great booming sound, the shockwave of the explosion.

The test is a success. Oh, and the earth isn’t destroyed either.

And so – a few weeks later – on the 6th of August, 1945,

their new bomb is dropped on the Japanese city of Hiro-shima.

And just a few days later another atomic bomb is dropped on Nagasaki.

As many as 200,000 people –

men, women, children,

mostly civilians –

were killed,

and many more suffered lifelong injury from radiation sickness.

Japan surrendered, bringing the Second World War to an end.

Light and sound – signifying death and destruction and conflict on an unprecedented scale.

It’s a true story, and today, today is the 6th of August,

today is the 78th anniversary of that first atomic bomb at Hiro-shima.

It’s a day when the world remembers those killed,

those injured,

[[those whose lives were affected,

the destruction wrought ]]

by those two life-destroying atomic bombs.

And

when we all hope and pray that it won’t happen again.

But the 6th of August is also a day that the Church has celebrated as a holy day

for hundreds and hundreds of years.

We heard the story in our gospel reading from Luke this morning.

Jesus and some of his disciples climb up a hill,

and there the disciples see Jesus transfigured –

shining white with brilliant dazzling light,

and they hear a great booming voice.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

Now, I’m not going to try and explain what happened,

or try to second-guess what the disciples “really” saw and heard.

But the effects of this light and this sound

are very different from the destruction caused by the light and sound at Hiro-shima.

This light and this sound have a meaning totally different from that of the atomic bomb.

And as a result, the disciples understand that Jesus’s message comes from God.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

Rather than death and destruction and conflict,

this bright light signifies

life and healing and peace.

That’s the life-giving message that Jesus brings,

the life-giving message that Jesus brings from God.

That God wants us to have life in all its fulness,

to live in love, and to care for one another

in the good times, yes –

and, even more so, when the going gets tough.

God wants us

– as Jesus says elsewhere in the gospels –

to feed the hungry,

to shelter the homeless and the refugee,

to care for the sick and the needy,

to lift up the oppressed,

to forgive and be reconciled with those who have wronged us.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

It’s the message that God, in Jesus,

saves us from the chain reaction

of hate and wrong-doing and death,

the chain reaction that leads to ever more hate and wrong-doing and death.

God in Jesus offers us an alternative,

an alternative chain reaction of hope and caring and forgiveness.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

It’s not an easy way out, though.

Caring and reconciliation can be costly too,

as we see up there, above me,

with Jesus put to death on the Cross.

Because not everyone appreciates caring,

not everyone appreciates it when people stand up for others,

not everyone appreciates it when people look for reconciliation.

But Jesus’s message is that this way is God’s way.

And in the Transfiguration, in Luke’s story that we heard earlier,

[[and also Peter in his letter that we heard too,]]

the disciples realize that Jesus’s message is God’s message.

“This is my Son, listen to him.”

And they do their best,

after Jesus’s death and resurrection,

to pass his story on to their successors,

and – and here’s the important bit –

not just to tell the story,

but to live as the community of people

who try to do those things.

And it’s into this community that we have come today

to see C_ baptized.

This is the community of people – here in this church in St Ives –

who are the followers of Jesus,

the successors,

(many hundreds of years later, with others here and around the world)

the successors of Jesus’s own disciples –

a life-giving, life-enhancing chain reaction.

Now, of course, we’re human, and we get things wrong.

We aren’t perfect

and we don’t always agree

and we don’t always look after one another as we should.

But we are that community,

that is what the Church is,

that is what the Church tries to be;

and we are committed to journeying together

and trying to understand and to live as that community,

the community of Jesus’s followers.

And so – today – we welcome C_ into this community.

Now, it’s a two-way thing, C_.

For your part,

you will affirm the importance to you of Jesus and his message,

and the importance in your life of the divine, of God,

and the importance in your life of this community of faith and prayer and worship.

And we, the members of that community,

we will affirm our support for you as you make this step.

We will journey together:

we will learn from you

as you learn from us.

We will do things together

to share the good news that Jesus shared with his disciples,

and to care for those among us and around us who are in need.

And we will do it all with God’s help.

We’ll have fun together

and sad times together.

If we are honest, we know that sometimes we might even get cross with each other.

But we know that that’s because we each care,

and that, in Jesus, through Jesus,

there is always forgiveness and reconciliation.

And if that sounds a bit like a family,

well, that’s because the Christian community, the Christian Church,

is like a family.

It doesn’t replace the family that we live with.

But it is a new family, God’s family,

that we each become part of at our baptism.

And it is into God’s family, C_, God’s life-enhancing family,

that we are now going to welcome you.

Amen.

0 CommentsCoronation Liturgy Talk

(The Coronation of Queen Victoria, 1838, painted by Sir George Hayter; Royal Collection Trust)

Last week I participated in a “colloquium” organized by Praxis on the subject of the Coronation, giving an introductory talk on the elements of the service or liturgy at previous coronations. (We don’t yet have details of the 2023 service.) The other major presenter was the Very Revd Dr David Hoyle, the Dean of Westminster, who is closely involved in the planning and will be a major participant at the service.

The slides I used at that talk can be found here, in two versions – a large illustrated version and a small version with no illustrations.

- illustrated PowerPoint (126MB); PDF (1.2MB); PDF with notes (588kB)

- text only PowerPoint (100kB)

Both versions contain some notes, and they can also be read in conjunction with my earlier post on the Coronation liturgy.

Additionally a recording of the colloquium is available on YouTube. My section starts at about 7 minutes in – do watch all the recording if you have time.

0 Comments

The Coronation Oil

The oil that will be used to anoint the king and queen at their coronation on 6 May has been consecrated in Jerusalem by the Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem and the Anglican Archbishop. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s website reports the details here, and that article is archived below.

0 Comments